The modern IWW has experimented with different approaches to organizing, including occasionally signing collective agreements. Nick Driedger looks at how these measure up against union contracts elsewhere.

The Industrial Workers of the World is a union with about 9,000 members today. It has a different mission than most unions in that it wants to replace capitalism with direct, democratic worker control over industry. The organization has many members who are members on paper but a growing number are in organizing campaigns, building an IWW presence on the job, with some covered by collective agreements. The purpose of this brief overview is to look at the IWW seriously as a union instead of as an activist group.

The recent revival of the IWW represents an interesting laboratory of different labor relations approaches. The early 2000s saw a generation of campaigns that tried to avoid the NLRB framework but maintained a public minority unionism approach. What they could not get with shopfloor power they got with media attention. They borrowed from lessons learned in street protest movements and tried to graft this approach onto a project of building workplace power.

Many in the IWW responded to this by downplaying the “going public” aspects of organizing and focusing more on knowing the workplace, bringing people on board, and making demands. Many IWW campaigns now are to varying degrees under the radar and focused on getting concessions from the employer instead of promoting the IWW brand through “earned media.”

Another faction in the IWW began to push for getting “serious” by simply organizing the way most unions do. These campaigns filed for certification elections and signed contracts in various different workplaces and these contracts show a variety of different approaches to bargaining and labor relations. There are contracts in the IWW that are substantially weaker than business union contracts alongside contracts that are much stronger. This article will look at a few examples.

Contracts in the IWW’s History

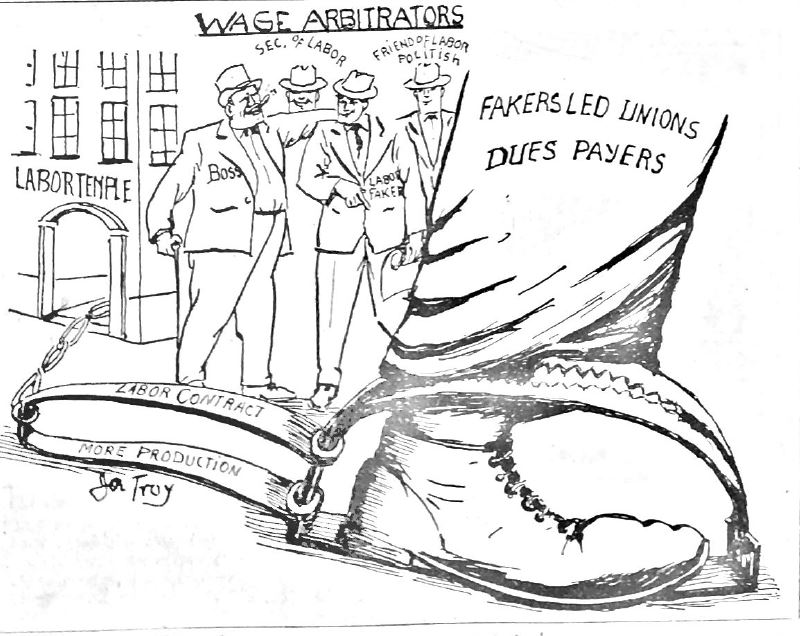

The Industrial Workers of the World inherited its position against “time agreements” from the Western Federation of Miners. This forbade the organization from signing any agreement with employers that was time-bound and has sometimes been interpreted to mean “nothing in writing” (this interpretation is not consistent in the early WFM or the IWW).

Many historians accuse the IWW of being an unstable union because of this position, but this argument is undermined by the facts. The Western Federation of Miners did away with the ban on time agreements in 1913, marking twenty years of union activity without contracts, covering over 45,000 members, including the largest single union local in the United States of America, the Butte Miners’ Local #1. The IWW held job control on the docks of Philadelphia with Marine Transport Workers Union Local 8 for about a decade, and held job control on vast swaths of the Midwest harvest for close to a decade. The IWW lumber workers were a transient workforce with a strong presence and notched consistent gains for workers in an industry where they arguably did not have a stable workplace to build stable unions in.

Historians tend to focus on where the IWW was the least stable and most spectacular, emphasizing large strikes, but then tie the argument about instability to the refusal to sign time agreements.

Often the academic history of the IWW covers only 1905-1917. This serves two purposes: it cuts the most important period of the IWW, 1913-1924, in half. It also ends the story with the triumph of the Russian Revolution. For those sympathetic to Communist Party politics, this makes the IWW a necessary prelude to the “serious” work; for those sympathetic to social democracy, it makes the IWW a necessary prelude to the red terror the Communist Party represents in the minds of many people.

Contrary to these histories, the IWW’s greatest numbers were actually in the early 1920s and most importantly these numbers were on the job and in shops. The IWW was not crushed by WWI oppression; they actually emerged from it stronger and more powerful only to collapse in a split in 1924.

The IWW also enjoyed a brief revival in the 1930s that is worth looking at closely as it represented an important era of experiments with contracts without many of the things that are common now, like no-strike clauses or management’s prerogative clauses. While the IWW was not unique in signing such contracts, they were unique in tying them to an explicit vision of a world without capitalism where workers do not just receive the full share of the product of their labor but would exercise control over that work too.

Contemporary Contracts

Contracts have been as controversial in the modern IWW as they were historically. The IWW’s 2012 Convention allowed for contracts (time agreements) but forbade the union from signing anything with a no-strike clause. Most IWW contracts at this point did not contain a no-strike clause. Language was written to allow for the maximum leeway for direct worker solidarity.

Many modern campaigns, like in the IWW of old, do not aim for a written agreement but see groups of workers settling concerns with bosses, often with pretty favorable concessions. While the employer is not tied by a contract, neither is the union, and often the gains last much longer than the union presence itself.

This is not a comprehensive list of contemporary collective agreements in the IWW but a selection of different approaches in order to illustrate the diversity of these agreements.

Bay Area Recycling Shops

Two long-standing collective agreements in the IWW are with the Ecology Center, dating to 1989, and Community Conservation Center, which dates to 2001. Both workplaces are located in Berkeley, California.

These are pretty typical contracts for an industrial workplace but notably the language in the Ecology Center contract lacks a no-strike clause and includes a clause allowing for the right to refuse to cross picket lines. Similarly, the Community Conservation Center contract does not have a typical no-strike clause and has similar right-to-refuse language with regards to picket lines.

Besides the no-strike, these contract really have no political content that would be different from a progressive union like the United Electrical Workers or a social movement union in Canada.

Burgerville Workers Union

This collective agreement covering five Oregon locations of a regional fast-food chain is the source of ongoing debate in the IWW. The no-strike clause was TA’ed knowing it was not constitutional in order to force the question of contracts in the organization.

The contract contains a number of questionable clauses around management’s rights, includes the unconstitutional no-strike clause, and the grievance procedure has a “loser pays” provision which means the party who loses the grievance picks up the full cost of arbitration. This makes grievances risky for the union and means the union can’t advance a grievance based on principle without paying a steep price.

Overall this is a very bad collective agreement but contracts are also rare in the fast food industry. Any more in-depth analysis of Burgerville (and this piece is not an in-depth analysis) is also going to want to account for the wins these workers have gotten on the job outside of the contract.

While many of those who support contracts have criticized their opponents in the IWW for not being pragmatic, the Burgerville contract points to the opposite problem: a lack of democratic coordination and honest conversations about the power they actually held led to a pretty weak contract. Winning strong contract language requires a considerable strike threat and the ability to affect profits. Either this bargaining unit did not sustain the support they had hoped for in the bargaining unit, the bargaining unit was not big enough to back up the demands they wanted, or workers in that industry just don’t have the leverage needed to make real wins. Judging by the IWW’s track record of concessions from food service employers outside of contracts, the problem is the first two scenarios and not the third.

The Dill Pickle Food Co-op

A small grocery store in Chicago is not the stuff that is going to turn around the entire Wagner Act model but it is the kind of place where innovative experiments can turn up. This contract is not unique among IWW contracts for its lack of a no-strike clause, but the grievance procedure is what makes it worth looking at. The grievance language explicitly says they do not surrender their right to take concerted action and it does not tie the union’s hands to use the grievance procedure as the sole (or even primary) means of settling disputes.

There have been several strikes at this workplace and a handful of failed attempts by the employer to challenge these strikes in front of the NLRB for being illegal. So far, all of the NLRB challenges have failed.

How far this language holds up is worth watching but it’s also worth noting that this language is likely not going to be easy to get in every bargaining round with every employer. However, one thing the IWW has that other unions don’t is a track record of sustaining campaigns without a contract or even certification. This gives them a much better shot at holding out for better language.

Stardust Family United

Stardust Family United is probably one of the most interesting and unique union campaigns in North America in the last thirty years. They are effectively the bargaining agent for an employer of about a hundred staff. They did not ask for certification and have never signed a collective bargaining agreement. The organization collects dues without checkoff and maintains a majority in the shop and a functioning Industrial Union Branch.

This is a 21st century workplace with labor relations that look more like the 1920s. Located in Times Square in New York, the workers (mostly singing servers) often work in show business when they are not at the diner. Issues are handled as they come up through conversations with management and if that does not settle it, direct action is resorted to. Do they win every time? Of course not: this is a power struggle. But they have made numerous improvements to their workplace without the drawn-out bureaucracy of a grievance process. The IWW presence in this shop is going on six and a half years of job control.

Overview

The IWW is often treated as a quaint holdover from times past, either some kind of anarchist social club for trade unionists, or maybe training wheels for real trade unionists before they earn their stripes.

I may no longer be an IWW member but writing this organization off is a mistake. Over the last 20 years they have managed to experiment with many innovations that a lot of other unions haven’t managed to make work.

The IWW has a model that can sustain a presence in workplaces with small shops, a type of workplace most other unions struggle with. It has made gains and improvements for thousands of workers through struggle and has trained thousands of workers to organize. Many of whom (like myself) wind up organizing for mainstream unions too.

The most important thing about the IWW though is that it tries to look beyond the Wagner Act system of unionism. This brief study leaves out dozens of successful campaigns, like CapTel, Frites Alors, and the Chicago Couriers Union. The IWW as an organization punches high above its weight class and is often underestimated. The lessons of the IWW are important not just for the IWW but the labor movement as a whole.

However, the IWW also needs to reckon with the fact that insofar as it does things the same as other unions it will get the same results. Sometimes it will get worse results. The IWW’s problem isn’t the arrogance that comes with the ambition of their goals, but the arrogance that comes with assuming the people who are running other unions are incompetent.

While the IWW may be falling far short of its ambition to topple capitalism it’s worth considering that this ambition in a union is what drives them to find ways of doing things less ambitious organizations may fail to see.

Nick Driedger is the Director of Labour Relations and Organizing for the Alberta Union of Provincial Employees and a frequent contributor to Organizing Work.