Food coops, housing coops, credit unions, and other such institutions are sometimes referred to as the “solidarity economy.” How do these institutions relate to working-class power? Do they offer working-class people some shelter or respite from capitalism? Do they perhaps even “create the new world in the shell of the old”? Nick Driedger and Eric Dirnbach, two veteran members of many institutions of the solidarity economy, debate these points.

Eric: We all noticed this recent article about the campaign for “postal banking,” where United States Postal Service branches would offer much-needed banking services for folks who lack access to bank accounts. The USPS actually used to do this up until the 1960s, and other countries still have it. This would obviously be helpful for many low-income people, who are forced to pay high fees at check cashing stores, and of course Wall Street banks hate the idea because they don’t want the competition. Unfortunately, according to the article, the national credit union association allied with the banks to lobby against it, which was news to me.

Now, I’m a member of a credit union and a fan of the concept. Financial institutions owned and run by their members are a great alternative to handing over our money to the standard, capitalist banks and increasing their power over us. Credit unions are in principle more accountable to their members and their communities, and have policies that are much more progressive than banks. And yet they took this bad stance against postal banking, deciding to protect their turf, just like the capitalists.

This reminded me of the recent Organizing Work exposé about bad labor practices and union-busting at a number of food cooperatives. I’m also a fan of food coops and have been a member of several, and those practices are extremely disappointing. Another problematic example is the Mondragon coop network in Spain, which I think is really impressive, but also incorporates a second-class tier of international workers who are not member-owners and who have even gone on strike against the coop.

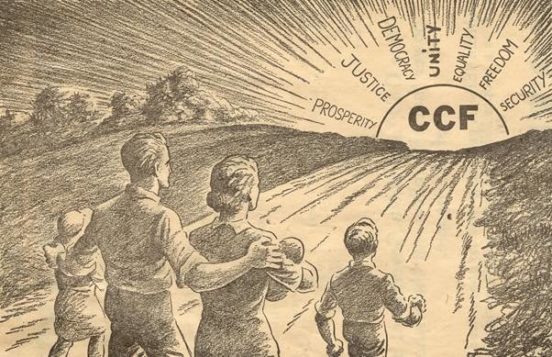

Overall, these are examples of “solidarity economy” organizations behaving like capitalist enterprises. The solidarity economy can be described as a network of organizations and practices like worker coops, housing coops, community land trusts, food coops, credit unions, time banks, community gardens and other entities that are alternatives to capitalist businesses. A segment of the left, and I would include myself here, believes one strategy (along with others like union organizing) to help transition beyond capitalism is to grow this economy in opposition to capitalist practices and prefigure the better socialist world that we want. A hundred years ago they called this idea the “Cooperative Commonwealth.” But these examples of bad, non-solidarity politics undermine that ideal.

Nick: In the article you mention, we see an example of an arm of the United States government being called on to provide a new public service. The City of Cleveland specifically called on the United States Postal Service to provide banking services through post office outlets. These calls are also coming from grassroots campaigns among postal workers’ unions in the USA and Canada, who want the government to expand services, better serve rural communities and undercut payday loan companies, which are often the only way for many working people to cash their paycheques, at exorbitant rates.

I am a member of four different consumer cooperative businesses, and had my first job at one of them. The United Farmers of Alberta is an institution where I live. At one time, it was a political party, and for a number of years, a long time ago, it was the government of the province. I am a member and buy feed for my chickens and ducks there, and when I was sixteen they gave me my first job. It had benefits and clear hours and a job description. It paid head and shoulders above what most businesses in rural Alberta will pay a teenager.

I am also a member of my small town’s credit union. The manager of this credit union is a big player in the local United Conservative Party. I pay my insurance through The Cooperators Insurance. The manager of this coop was our New Democrat (social democratic party in Canada) representative in the provincial government that just fell in Alberta a couple of months ago. In the past, I have voted for left candidates for the board at Mountain Equipment Co-op (a camping supply consumer coop popular in Canada) who wanted to push for stronger ethical purchasing guidelines and support the cause of Palestinian rights.

Cooperatives in Western Canada are political and there is politics inside of them. They are often on their local chambers of commerce, and there is both a left wing inside the cooperative movement as well as a very strong right wing.

Where I live, coops are also a part of the local history. My family in a Saskatchewan farming community have worked for generations at a consumer cooperative simply called “The Co-op,” which provides groceries and fuel in many communities. In many rural communities in Western Canada, no one would have electricity if not for early rural cooperatives. Later, government services followed, like Alberta Government Telephones (which was privatized in the 1990s). Often coops would establish services that would be picked up as public services later. The words “Cooperative Commonwealth” have a deep resonance with people and a history here. Even a lot of conservatives consider the history of the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (forerunner of the New Democratic Party) a history working people and farmers can be proud of on the prairies.

Eric: That is a fascinating history and I’d love to learn more about coops in rural areas. Clearly coops were organized over the years to meet the needs of rural residents. Agricultural supply and electrical coops are great examples of this. More modern examples are the internet service coops.

I’m more familiar with coops in an urban setting. I’ve lived in my housing coop in New York City for about ten years and was just elected to the board, so I’ve been thinking about this place a lot. Morningside Gardens, with almost 1,000 apartments in six buildings, was founded in 1957 and has a pretty rich history of cooperative activity, with many committees, clubs and other organizations formed. Folks started a cooperative workshop for woodworking and ceramics, a nursery school and a retirement service in the 1960s, which are all still running. The retirement service allows senior residents to age in-place and not have to move to a nursing home.

Members here have also been involved in community-issue organizing for decades, such as supporting local libraries, fighting for good subway and sanitation services, and campaigning for better local zoning to restrict luxury condos. Residents have formed several babysitting coops over the years. A theatre group was formed in the 1980s which still exists. In the last few years, several buildings have started a “Neighbors Helping Neighbors” mutual aid program, which is like an informal timebank where folks help each other with household tasks.

We had a food coop for over 30 years; that closed in the 1990s. I spent some time reading our old newsletters to learn about it and write up a history. The food coop members advocated for better consumer protection and product labeling laws in the 1960s and 1970s when the entire grocery industry was against more regulations. The coop also supported the United Farm Workers grape boycott and the Nestle baby formula boycott. In the 1960s, it started a credit union, which lasted for 15 years, so low-income members could have access to loans they couldn’t get at a bank. The coop also helped start at least two other food coops nearby, with funding and technical assistance. It made a small profit in most of its years and often returned a rebate to the members, thus keeping money in the community and out of the hands of a billionaire grocery boss. And it was a union shop. One of my neighbors worked as a bookkeeper there in the 1970s and 1980s and still gets the union pension today.

All this seems really positive to me and was enabled to a large extent by the cooperative setting. Of course, some of this activity could happen in a similarly-sized apartment complex of renters, owned and managed by a landlord, but a lot of it wouldn’t. Bosses and landlords monopolize power, decision-making and wealth. Workplace and tenant unions fight to expand worker and tenant power, of course, but ultimately the boss or landlord still owns the property and extracts the surplus value and rent. The process of people running their own key institutions requires a lot of volunteer work, but this cooperation I think builds skills and confidence and creates more opportunities and the desire to work together on other projects.

Now, I don’t want to overstate the situation here; this isn’t Full Communism. Of course there have always been folks who see it as just a nice place to live and are less engaged in its internal life and politics. And capitalism has intruded on our utopia. The coop was “limited-equity” for decades, meaning that apartments were priced at below market value to keep them affordable. This was because our coop originally received tax breaks and other assistance arising from the 1949 Housing Act, which was intended to create affordable housing (and has a complicated history). Then there was a contentious, long-running debate starting in the 1990s where a majority of residents voted to shift to market-rate pricing over time.

There were a number of arguments for this change, but a key reason of course was that folks could sell much more valuable apartments in a rising housing market. This reduced the stock of affordable apartments in the city, and in my view, prioritized personal gain at the expense of our legacy as an affordable housing coop. I recognize that this is another example of the pressures of capitalism eroding the solidarity economy over time.

Even though we lost something essential there, we still have a dynamic cooperative community. And there are thousands of other housing coops in New York City as well, many with similar stories to tell, I see all this history of cooperative activity as part of a broader community struggle against capitalist social relations.

Nick: Recently, during a strike in Saskatoon, The Co-op took a hard line against their staff. In Cleveland, the credit cooperatives protected their turf against an expansion of public services that would benefit a lot of working people. The typical answer to this is that everyone has their sellouts and a lot of unions and political parties make compromises that undermine their mission too. But there is something more at work here with cooperatives.

If a business is trying to bust a union, one of the more common lines they will take is that the union is a business too, and their business is selling themselves to workers. But a union takes dues and serves a constituency.

What do I mean by a constituency? A constituency is a group whose identity is shaped by being subject to someone else’s power, and the boundary of that constituency is the reach of that power. A union has people it serves, and while money is a key resource in how it serves those members, the relationship the members have in a union is framed by a direct power struggle with the employer.

So while unions can “sell out,” they are measured by their ability to directly empower their members and by their ability to strike a bargain with the opponent they are struggling against. That struggle is a collective one; the union acts as a way to control the labour supply to employers, and that creates a social identity.

For coops it is a lot more vague. They exist to “remove the middle man” and have their members engage with the market more directly. There is a long history of this sentiment on the Canadian prairies, with groups like the Social Credit Party (the party that was in government in Alberta after the United Farmers of Alberta fell). Coops can break both ways politically because they start from a consumer position and members are not struggling collectively, they are struggling individually. While a coop is an example of people coming together as a group, they are still engaging in personal consumer choices and the coop is merely acting as a democratically-managed middle-man. The most conservative unions may act like this, but when the heat is on, they take strike action, which changes the relationship a lot. There is no equivalent to that in the cooperative world.

Without that animating conflict, coops drift. Now is the coop movement useless, or worse, hopeless? No. Coops can be a part of a social movement if they tie their struggles and interests to the class struggle. Housing cooperatives are often a practical solution to a rent strike or a struggle for social housing. But if it just ends there and is not part of a fight to expand that system and support people who organise tenant unions, it will collapse. For this reason, coops need to be subordinate to unions, especially unions that are outside the coop sector. Their management decisions need to be made in the interests of the broad struggle, especially where that struggle is most direct.

Eric: I like this concept of the “animating conflict.” If unions are the main institution that workers form to wage the class struggle, then are coops another way of engaging that struggle? I would say yes, but of course that struggle is on a different terrain. We are running our own institutions, which puts us in competition with capitalists in the market. But I can understand the argument that struggling against capitalism by trying to compete against it is playing on the boss’s terrain. You either lose or start to operate like a capitalist to survive.

It’s an interesting point that members of, say, a food coop or a credit union are not in a collective class position, but are a group of individual consumers working together. And so the politics of the organization are not guided by class conflict, but can “drift” in response to capitalist imperatives. It’s possible then for coops to disengage from the broader class struggle. Perhaps this is even somewhat true for members of a worker-owned coop, who have more of a collective class position, but also don’t have a boss to fight against.

However, the cooperative movement has seven guiding principles that are supposed to shape the movement within a solidarity framework. I guess we could say that within capitalist competition, these principles help, and are often realized, but don’t always stop coops from drifting politically.

Thinking of my own housing coop, we have for decades been engaged positively in the community, but our move to market rate apartments was definitely a political drift. And we could perhaps be doing a lot more to help tenants form their own housing coops or tenant unions, and really see ourselves as more a part of the housing justice movement. However there’s nothing structurally pushing us in that direction, the way tenants are inevitably thrown into conflict with a landlord, or workers with their boss. It would depend on coop members deciding to organize around that.

I agree that the coop movement should absolutely have stronger ties to the labor movement. From what I’ve seen, coops and unions operate in largely separate worlds, whereas in the 19th century they were more considered to be part of the same movement. But there has been an effort over the last decade to form “union coops,” where members of a worker coop are also union members, which points in that direction of closer collaboration. Solidarity economy groups, always under pressure from capitalism, have to see that their survival and growth depends on engaging with the broader class struggle.

Nick: So I think the thing about capitalism is that competition in the market isn’t just “the boss’ terrain.” I think the problem here is that capitalism isn’t just about how bosses compete or that bosses are bad. Capitalism is the terrain itself. We aren’t just, or even always, trying to beat the bosses; it’s competition itself that drives a lot of the problems in our economy. Again, coops can play a role in overcoming that dynamic, but they can’t take the lead, and at some point the coops need to have a subordinate role, maybe even sometimes a role that means they answer to other groups (like unions).

Unions don’t give strike funds to keep an edge on non-union workers, they in many cases are actually intervening in the economy to be less competitive.

All groups are under pressure from capitalism, but capitalism is the rule of capital or money; it isn’t just the rule of bosses. When unions undergo a struggle, they allocate resources democratically, based on need. At the very least, in a commercial coop like the ones I listed above, these organisations allocate resources based on their need for a competitive advantage within the confines of their own principles.

Overall, I do see a role for coops, but we need that role to be one that heavily limits their involvement, and that means they are junior partners in the struggle. Not because we can’t trust their principles — the principles are fine — but because we can’t trust the basic mechanics of how they operate and the way our economy currently operates.