Marianne Garneau responds to a picket-crossing professor.

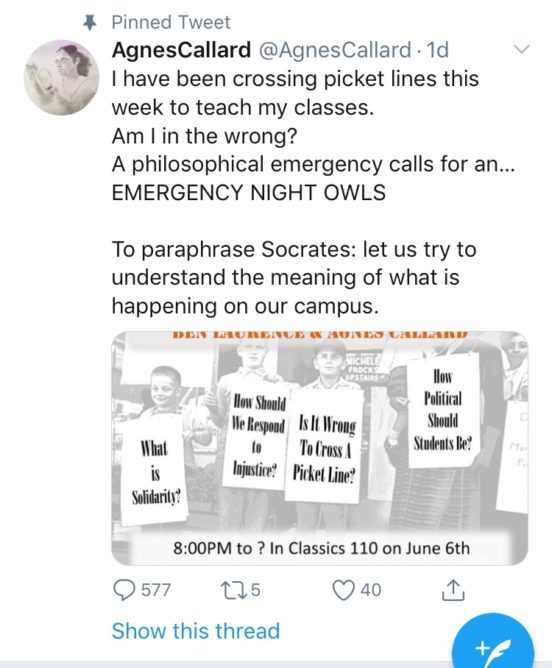

Yesterday, University of Chicago professor Agnes Callard tweeted that she had been crossing picket lines all week set up by graduate students at the institution, asking “Am I in the wrong?” As the expression goes, every day on Twitter there is one main character; the goal is never to be it. Callard was promptly ratioed. An essay she wrote in The Point, titled “Persuade or Be Persuaded” also made the rounds.

Years ago, when I was attending the New School, graduate and undergraduate students occupied a building in protest of the administration. There were several issues on the table, including the incredibly paltry wages of graduate student workers. A senior professor in my home department of philosophy remarked that if he had been sent in there to negotiate with the students, he wouldn’t have engaged on the issue of wages, or the administration. He would have said, “Yes of course you are right, but we can’t start with Marx; we have to go back to Hegel. And of course, to talk about Hegel, we have to go back to the beginning, to Socrates.” And he would have led them through a reading of the Republic, or perhaps the Symposium. I stood back in a mixture of admiration and horror. Now this, I thought, is a skillful destroyer of resistance.

That kind of strategy of misdirection is exactly what Callard has done in her essay, about civility and Socrates, in response – somehow – to the graduate student fight, and her decision to cross the line. It’s 1,500 words about the need for conversation and the importance of persuading your opponent. It is especially important, she says, to persuade your political opponent. You can’t just say, “oh well, to each his own” when it comes to things like abortion and taxation and prison. Things are going to come down one way or another. We share a world with our opponents. We need them to come to see things our way. The essay culminates in Callard’s defense of her intention to bravely host a debate about the strike.

In the first place, it is remarkable how she has written an entire article about the importance of debate about even the most controversial of topics, and never once engaged with any of the arguments she has been given as to why she should respect the graduate students’ picket. That’s masterful misdirection (same as my philosophy professor). “Let’s not debate the strike – at least not yet, not while it’s going on, not in the real world like on the picket line – let’s first debate the value of debate.”

Here is the kicker, however. Callard is actually undermining debate. The strike is a demand for recognition. Graduate Students United is trying to get the University of Chicago administration to formally acknowledge it, to be able sit down and negotiate graduate student wages and working conditions. It’s trying to make a debate happen.

Callard thinks herself very brave to refuse to cancel her event, despite the “resistance” she says she has encountered. The difference is, Callard’s event as such has no stakes. It is a theoretical debate taking place in rarefied air. She describes being “lucky enough to work in one of the most intellectually open places the world has ever known” but doesn’t consider for a moment that the price of that freedom is shunting away the politics and engaging in a purely theoretical mode. As much as she would like to imagine she is standing up for free speech (and in some sense she is), doing so is incredibly easy when the discussion is kept to a lecture hall, after hours. In other words, where the discussion is “academic.” Callard, like many others, mistakes stepping back from the real world for sober thoughtfulness.

There would be something at stake at the bargaining table. But that discussion may well never happen, because people like Callard either don’t think it important enough, or else can’t connect the dots enough to understand that power needs to be leveraged to force certain conversations to take place at all.