A DOL investigation of a worker center seeks to reclassify it as a union. Eric Dirnbach and Marianne Garneau look at the differences between these kinds of organizations, and the potential impact of this change.

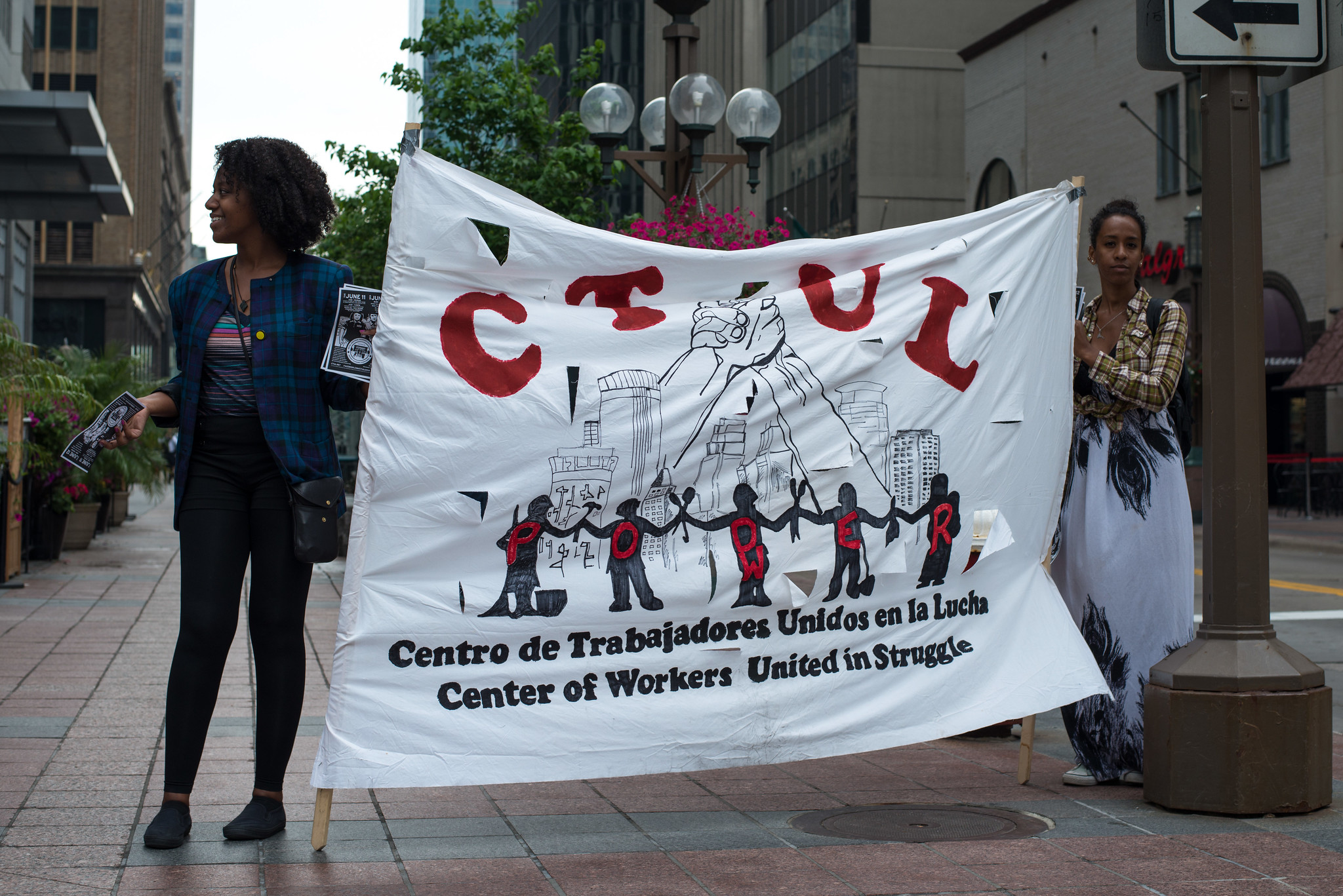

Image © Fibonacci Blue, Flickr

A recent article disclosed that the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) has been conducting a two-year investigation of the Minneapolis-based worker center Centro de Trabajadores Unidos en Lucha (CTUL). A newly uncovered letter sent to CTUL indicates that the DOL “has reason to believe that CTUL is a labor organization” based on its activities organizing workers. This case is still unresolved, but it looks like the DOL is trying to reclassify CTUL from a 501(c)3 charitable organization to a union.

This is rightly seen as a political attack on worker centers, organizations that have played a major role in fighting for improved wages and working conditions for low-wage, and in many cases, immigrant workers. Hundreds of worker centers have formed over the last few decades as an alternative to unions in order to provide services and organizational assistance to workers facing wage theft, immigration issues, and other problems. Worker centers engage in a range of activities, from educating workers about their rights, to pressuring employers, to lobbying for legislative change — using tactics that range from media campaigns to pickets. Right-wing opponents such as the Chamber of Commerce have lobbied for this reclassification for years, arguing that worker centers are basically union front groups, since they sometimes receive union funding and have some similar campaign tactics and goals.

The DOL process appears to require an investigation of each worker center’s activities, rather than a blanket reclassification of all of them, and that’s a slow process. However, this CTUL investigation may have a chilling effect on some worker center organizing activity, and could possibly sow some doubts about the model among funders.

The broader question raised is, what would the implications be of classifying worker centers as unions? A full analysis is beyond the scope of this article but we see at least three areas of change: regulatory, financial, and operational.

Regulatory differences

The main regulatory issue is the reporting requirements of the Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act (LMRDA) of 1959. Depending on your view, the LMRDA was passed to help root out union corruption and promote internal democracy, or burden unions with rules and paperwork. It requires that unions submit annual disclosure forms to the DOL that include financial information, which is then available to union members. This would be an extra administrative burden on worker centers, who currently do not have to report to the DOL. Moreover, LMRDA also has rules on democratic officer elections and overall union governance. This may have an impact on worker centers, since they currently don’t have required elections and would have to develop them. Although in cases where a worker center has no or minimal dues-paying membership, it’s unclear what that would look like. Those may be the least likely to be reclassified.

Financial differences

Since worker centers in the US are generally registered as 501(c)3 organizations for tax purposes, this means that roughly speaking they are entities that contribute to the public good. Grant-giving foundations also fall into this “3” category, but unions do not — unions are deemed to serve their members, not the public at large. Unions have a unique designation, as 501(c)5 organizations.

Speaking in broad terms, both “5” and “3” organizations are tax-exempt. But donations to “3” organizations are tax-deductible. 3s are highly regulated by the IRS because they enjoy this specific privilege of being able to use tax-deductible or pretax money. Money can move between 3s fairly easily, because those organizations enjoy the same status and are subject to the same scrutiny. But money cannot as easily move from a 3 to a 5. Otherwise, this would be a way of laundering pretax dollars to unions and other organizations that are not eligible for tax-deductible donations.

Technically, it would fall to the IRS, not the DOL, to change a worker center’s designation from 3 to 5. The DOL’s opinion about what constitutes union activity may differ from the IRS’s opinion about what constitutes public good versus member interest. But if that did happen — if worker centers were reclassified as 5s — this would likely impact contributions from organizations like foundations.

How much does foundation funding matter to worker centers? A 2018 study (“Sizing up Worker Center Income” by Leslie Gates et al) found that “foundation grants were the most prevalent stream of funding for worker centers” — even concluding that “worker centers would not be able to exist, let alone flourish, were it not for grants from charitable foundations”. One research finding cited by the study indicates that “61% of worker center funding came from charitable foundations.” If foundations were suddenly unable to contribute to worker centers, the funding loss would be dramatic.

Could worker centers replace foundation funding by cultivating another revenue stream? Right now, worker centers receive individual donations, although it’s hard to say what percentage of their revenue comes from this. If they were reclassified by the DOL and IRS as labor organizations, this funding source could be in jeopardy, as contributions would no longer be tax-deductible. Another revenue source is labor unions, but the research above found that “funding from labor unions serves as a minuscule portion of worker center revenue overall” — only around 1.1%. This is consistent with news of labor unions moving away from funding worker centers and initiatives like the Fight for 15. What about member dues? Currently, worker centers “get almost no funding from membership dues” — their total revenue from dues in 2012 was 1.8%. Moreover, “the vast majority (68%) of worker centers did not receive any funds from dues.” This is often attributed to the fact that the population they serve is lower-income and economically insecure, but could also reflect the fact that it is much easier to get revenue from foundations and grants than it is to generate and maintain an entire infrastructure of membership and dues payment.

Operational differences

If considered unions, worker centers could be subject to unfair labor practice (ULP) charges outlined in Section 8(b) of the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA). These ULPs were added to the NLRA by the infamous Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 as a way to weaken unions. The one that gets the most attention related to activities of worker centers is 8(b)(4) regarding what are often called “secondary boycotts.” Among these rules, a union can’t engage in “forcing or requiring any person to cease using, selling, handling, transporting, or otherwise dealing in the products of any other producer, processor, or manufacturer, or to cease doing business with any other person…”

The reason this comes up is that it’s very common for a union or worker center to have to confront a secondary employer that does business with a primary employer. In the case of CTUL’s campaign at Target, CTUL wanted to improve conditions at various janitorial companies (primary) that had contracts to clean Target stores (secondary). Any protest directed at Target is secondary activity. These kinds of protests are also needed to deal with the increasingly common “fissured workplace” where various pieces of work are often split up and contracted out to other corporate entities.

Worker centers are generally considered to have more freedom to conduct secondary protests because they are not governed by union restrictions under Taft-Hartley. Robert M. Schwartz, labor lawyer and frequent Labor Notes contributor, outlines secondary activity rules in his book No Contract, No Peace. He makes it clear that unions have the absolute right to conduct secondary campaigns provided there is no coercion. The courts have generally interpreted this to mean that unions can’t picket the secondary employer. Handbilling and displaying a banner are fine, but no picketing, meaning holding signs and walking around near the entrance to the employer. If this sounds like a strange distinction, it is, but the courts have taken seriously the possibility that picket lines are confrontational and coercive activity and have banned it in these cases. Worker centers presumably have the freedom to picket the secondary employer, among other activities. Worker centers can also sign agreements with secondary employers to, for example, use responsible contractors. Unions generally can’t do this.

The other main point about secondary activity is that unions can’t ask secondary employees to stop work. For example, a union for candy workers couldn’t ask grocery store workers (secondary) to not handle goods from their employer (primary), or ask them to go on strike. This is why unions always have a disclaimer on their secondary protest flyers that they are not asking anyone to stop work or not make deliveries. Worker centers and other groups don’t have these restrictions (although in either case, it’s risky for those secondary workers to strike in support of the primary campaign). In this example, a labor union drew a ULP for secondary activity, and in a possible harbinger of things to come, so did a worker center participating in the same campaign, which they settled. If reclassified as labor unions, worker centers would be subject to the same penalties as unions, and so would likely have to leave some tactics behind.

Worker centers at a crossroads?

Let’s revisit why worker centers formed in the first place. They proliferated in the 1990s and 2000s as employment in union-dense industries like manufacturing was replaced by casual, part-time jobs in sectors like the service industry. Worker centers arose to address the compelling need to provide assistance to these workers, who faced terrible wages and working conditions, and were subjected to wage theft, unsafe work, and other abuses. Organizing these workers into unions through standard election and contract campaigns seemed daunting, given high turnover rates and the fragmentation of this labor force by casual and part-time status.

But worker centers are in a weird position because, to use Jane McAlevey’s framework in her book No Shortcuts, they engage in a mix of advocacy and organizing. On the advocacy side, they use foundation funding to pay for professional staff like lawyers and social workers to pursue redress when the law is violated, or legislative changes on behalf of workers. On the organizing side, worker centers often present themselves as engaging in deeper activities, where workers are active members who are empowered to fight collectively and militantly on their own behalf. We can acknowledge that they take on some of the same functions and even same activities as a union, even if they don’t seek official recognition and a collective bargaining agreement.

As Steve Jenkins, an attorney and community organizer, has pointed out, the critical question remains whether even those more militant worker centers are leveraging social power against their targets. Social power is the coercive leverage groups have as a result of their position. Workers have coercive power against their employers as a result of the fact that they produce the goods and services and have the ability to withhold their labor. That’s the essence of what unions are or do — even if they decline to use the strike option for long periods of time. Worker centers, even when targeting employers, most often gather a diverse group of concerned community members, rather than a group of workers in the shop. The actual workers themselves sometimes play a symbolic role of giving testimonial to the injustice they face. How easy would it be for most worker centers to pivot to the kind of organizing that unions do and leverage they use?

Likewise, how easy would it be for worker centers to pivot from foundation funding to a dependency on membership dues and democratically-elected leadership? Some have pointed out that, as worker centers have come to rely more deeply on foundation funding, they have retreated from confrontational activity to “employer alliances and market-based initiatives.” Some worker centers have morphed from nimble, grassroots organizations challenging injustice to partnerships in workforce development, as a result of the “repeated institutional negotiations between strategic philanthropists and … worker center staff.”

Again, are worker centers unions in disguise, as the right alleges?

If the DOL (and IRS) pushed to reclassify worker centers, it may force them to make an important choice — either remain a 501(c)3 and retreat to non-confrontational advocacy, or continue organizing workers and get regulated and funded like a union.