Carmen Molinari argues that viral boycott calls like the recent one against Amazon “point us away from the hard work of building real power.”

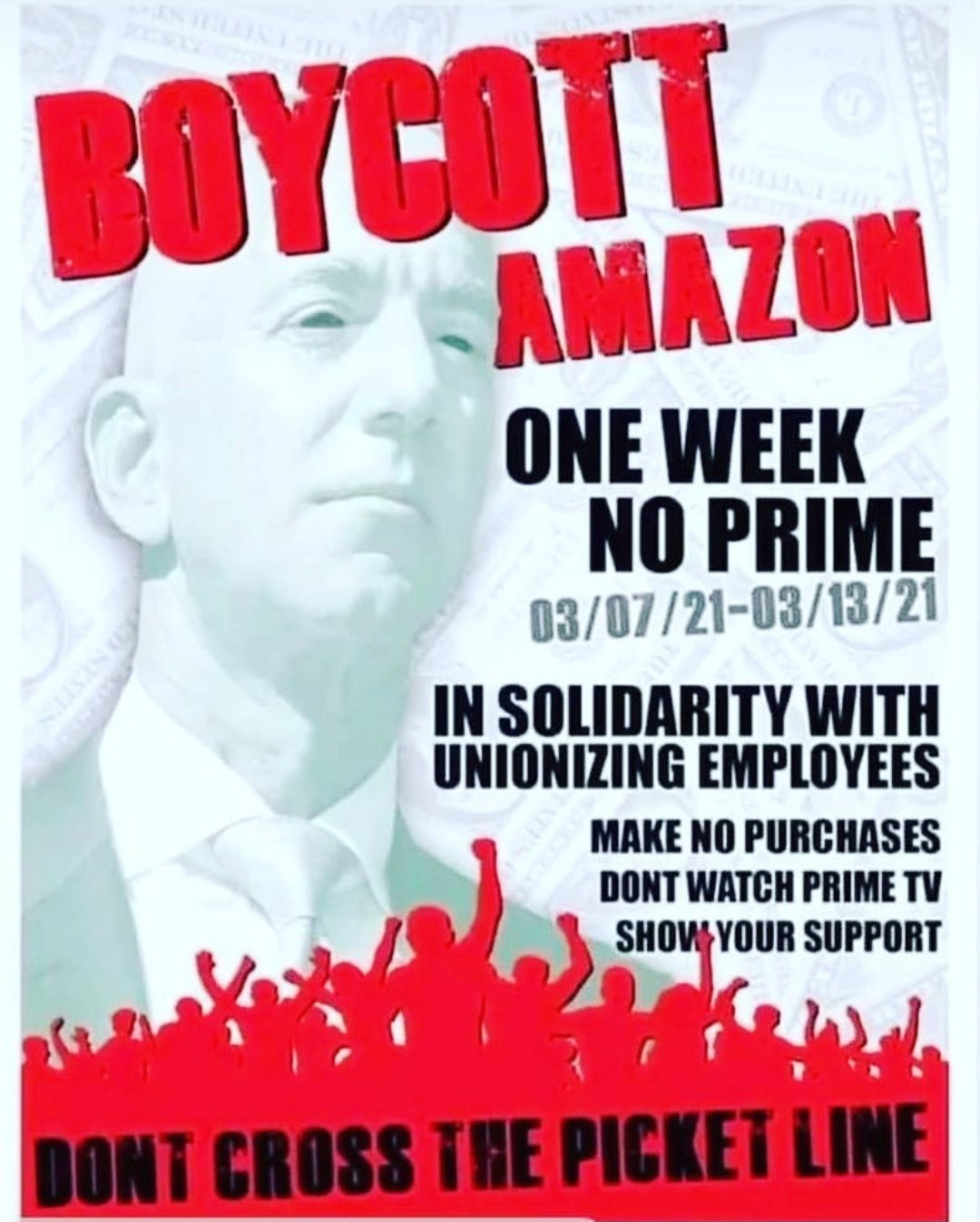

This week, an image calling for a one-week boycott of Amazon started making the rounds on social media. “In solidarity with unionizing employees,” the call also used the slogan “don’t cross the picket line.” The source for most users sharing the call seemed to be a blog post from a union PR firm. Soon, the content of social media shares evolved: although the blog post is clear that the boycott is intended to support workers taking part in an NLRB election with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union in Alabama, popular tweets claimed that Amazon workers were on strike.

As the posts propagated and multiplied, Huffington Post labor reporter Dave Jamieson tweeted confirmation from a spokesperson for RWDSU that they had nothing to do with the boycott call: “I’ve seen a bunch of viral tweets about boycotting Amazon in solidarity with the warehouse workers in Alabama. To be clear, the union involved in the election @RWDSU has NOT called for a boycott and has nothing to do with this, a spokesperson confirms.”

Why wouldn’t the union call for a boycott? Amazon is a widely hated company and, as we saw, boycott calls can gain significant traction online and make more people aware of the election and maybe even of Amazon’s union-busting practices if they start looking for more information. Despite this, no union with members at Amazon has ever called for a boycott. Workers at Amazon warehouses in Germany and Spain have gone on strike and still not called for a boycott. So what gives? What is a “digital picket line” anyway?

If you cross a picket line of an incompletely struck grocery store, do your shopping, and leave with your food, the company gets what they want. If you order on Amazon during a hypothetical big strike, you don’t actually get your order, and more importantly, Amazon doesn’t get your money. They don’t charge your card until the item is in a box on a truck. This is where workers’ power is. Amazon has a whole set of tracking systems to ensure that orders make their delivery time “promise,” and broken promises are taken very seriously. The most important metric when a worker or manager is told to write up a document on an incident that disrupted production: how many promises were missed? Within a warehouse, for every order, the system calculates the last possible time it needs to come off the shelf to make sure it’s on the truck it needs to be on to make that time, and there are workers whose whole work assignment is to rush orders that are at risk.

Amazon also carefully manages its labor force. When there’s not enough work on a shift, they “offer” a certain number of slots for workers to leave early (unpaid, of course, but not coming out of workers’ tiny budget of flexible unpaid time off). A well enough organized boycott that really cut into the volume of orders would mean Amazon sends workers home without pay.

It would also make a strike have less impact and leverage. That’s why I always assume boycott calls come from outside the house. If a group of workers did call for a boycott, it would be a sign to me that they either hadn’t done analysis of how the business works (unlikely — workers are smart and every Amazon warehouse worker I’ve talked to who’s involved in organizing pays attention to how production and their workplace work) or more likely hasn’t actually organized workers to the point they can use their power, and so hopes to substitute for that with some kind of “public pressure” or “brand campaign.”

Eric Dirnbach’s article Labor’s last resort: Understanding the boycott strategy explored how unions have used boycotts when they lack power in the workplace. Dirnbach cites the most famous labor-related boycott in the US, the United Farm Workers grape boycott, as a success story where the consumer boycott was essential to winning the campaign for UFW recognition and hiring halls in the fields. Frank Bardacke’s Trampling Out the Vintage: Cesar Chavez and the Two Souls of the United Farm Workers paints a different picture of the cost of that success. Bardacke details how the boycott pulled both UFW volunteers and farm workers themselves from their work organizing workers to months-long assignments in distant cities organizing progressive consumers to boycott:

With most UFWOC staffers stationed in boycott cities, a “skeleton crew,” a term visiting journalists typically used, was left in Delano. Large numbers were not needed there, as UFWOC’s primary interest was no longer organizing farm workers. No one doubted that the boycott was the key to victory. La huelga had become a mythic rallying cry, a call to general rebellion rather than a specific reference to workers’ withdrawal of their labor power. The dogs told the story. Chavez’s first German shepherd guard dog, which Jacques Levy helped him train in 1968, was named Boycott. The second dog was named Huelga.

This story points directly to the organization’s change in focus from workers to consumers as the subjects of the UFW’s organizing. That change is the surface level of deeper shifts in workers’, union staffers’, and the public’s mental models of working class identity, power, and solidarity. Farm workers doing boycott organizing were trained as speakers to use their personal stories when addressing audiences of urban activists and consumers. The exploitation and oppression they’d suffered at the hands of their employers was a sad story of injustice intended to inspire sympathy and maybe even guilt in the hearts of middle-class urbanites seeing for the first time the brutality of the system that brought them fresh produce year round. This narrative is even more popular today, perpetrated by worker centers and labor nonprofits as part of their media and fundraising strategy.

This worker disempowerment goes hand-in-hand with the empowerment of consumers. In UFW’s case, the workers they were organizing and the consumers they were targeting with their boycott were disjoint sets: farm workers were not major consumers of table grapes. But from a bigger picture view, all consumers are also either workers or bosses/owners. Encouraging workers to take action in our role as consumers shapes our ideas about where our power comes from. Boycotts aren’t effective at building worker power even if we completely intend them to be or intuitively feel them to be.

What they are really effective at is turning our identities as workers into just another mode of consumption: buy the IWW swag, share the right thing on social media, don’t shop on Amazon this week. Feel connected to a working class movement. Spend your time off on Leftbook and then come into work and overhear your coworkers talking about politics and be reminded they don’t agree with you… well, you didn’t want to talk to them anyway. If they don’t want to boycott Amazon with you this week, they’re hopeless. No use talking to them about your shared issues at work when they don’t seem to share your values. As with UFW’s huelga that grew as a rallying cry in inverse proportion to their efforts towards actual strikes in the fields, third-party boycott calls let working-class people feel like we’re acting in solidarity with a simple act of choice in where we buy the things we need. But it’s an illusion, and a seductive one, designed by capitalism to keep us pointed away from the hard work of building real power.

When questions about the legitimacy of the Amazon boycott call started circulating on social media, some people quickly retracted their previous support, apologizing for being caught up in the moment and not checking the source. Others doubled down: sure, this call may not have come from workers, but we should boycott anyway in a show of solidarity. Or this call may not be legitimate, but if you really want to support Amazon workers and union power, you should find alternatives and never shop on Amazon at all. Buy from local small businesses instead! The idea that we can shop our way out of capitalism is absurd when you look twice at it: every type of employer union-busts; the only reason most aren’t actively engaged in union-busting tactics at any given time is that they have no organizing campaign to fight. A tactical boycott against a smaller company with clear demands and good organization can help workers win specific gains when they don’t have the power built on the shop floor, but unlike a win by workers themselves, it doesn’t build their power and confidence for future demands. And it shores up the idea of consumer “power” through consumer choice, an idea that enlists workers-as-consumers in support of capitalism itself. After all, without a market economy, where is your consumer “power?”

Amazon still makes money hand over fist and their stock prices have gone up 50% during the pandemic. Negative public opinion about the company doesn’t seem to have harmed them in the least. But they’re still dependent on their workforce. And their heavily automated, just-in-time logistics network that extracts maximum value from workers makes them all the more vulnerable to concerted worker action.

Amazon is the second-largest employer in the US, essentially an industry in themselves, and they’ve brought hundreds of thousands of workers together under the same system of punitive discipline and control. This centralization and standardization gives workers obvious shared issues, shared interests, and a shared enemy. The power is there for the taking, if we can build it.

Carmen Molinari is a tech worker and organizer with the IWW.