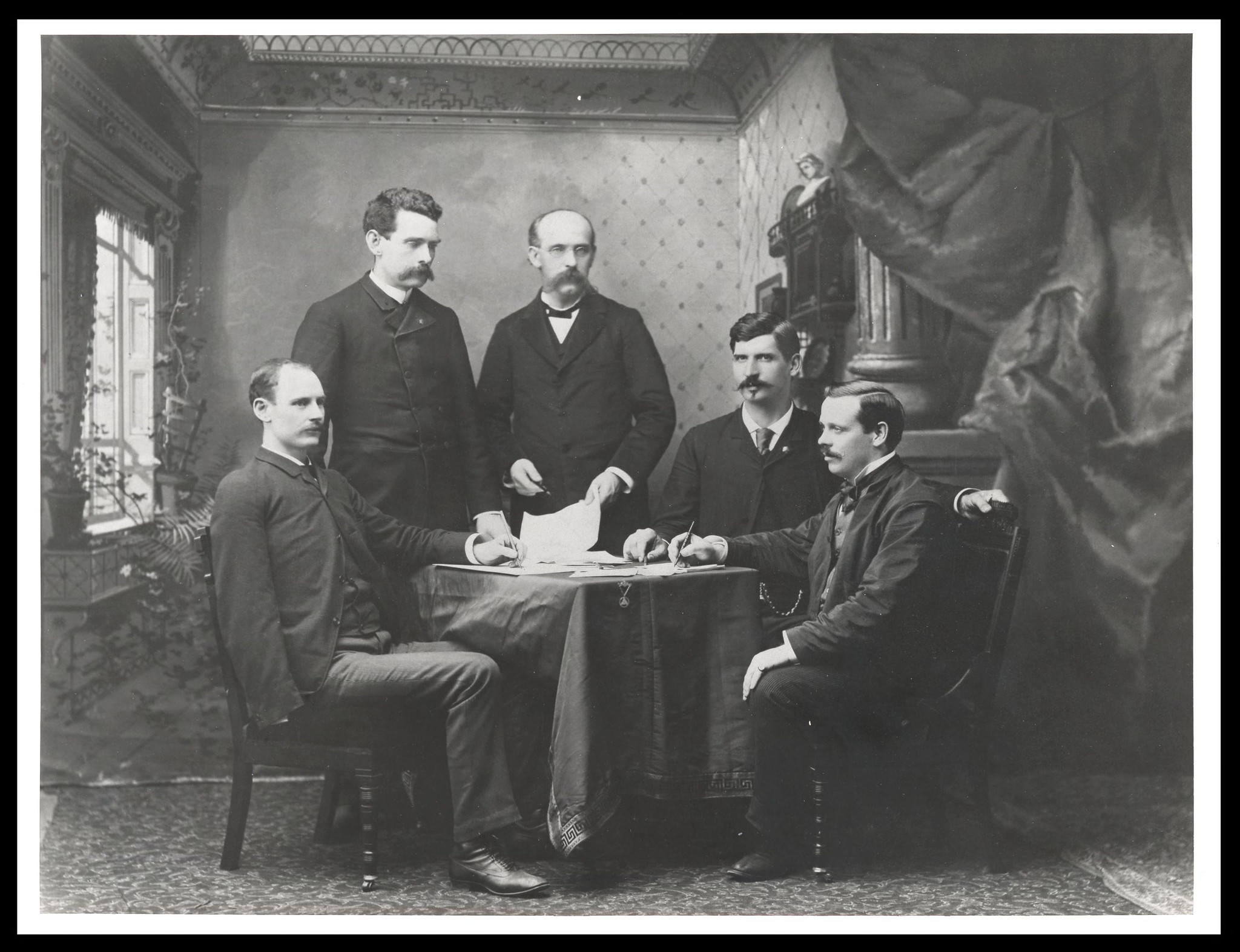

Robin J Cartwright explores the rise of paid officers and staff in the Knights of Labor and the corruption that ensued. The second in a multi-part series exploring the history of paid officers and staff in labor unions. Read the first installment here. Image: Knights of Labor John W Hayes (standing, left) and Terence Powderly (standing, right), circa 1886, via Washington Area Spark (Flickr).

In 1886, workers across the United States went on strike for the eight-hour day, local labor parties in state and municipal elections proliferated, and a growing anarchist movement achieved unprecedented levels of notoriety. Commenting on these events, Friedrich Engels, co-author of the Communist Manifesto with Karl Marx, wrote, “a revolution has been accomplished in American society such as, in any other country, would have taken at least ten years… On the more favored soil of America, where no mediæval ruins bar the way, where history begins with the elements of modern bourgeois society as evolved in the seventeenth century, the working class passed through… two stages of its development within ten months.” In the midst of this tumult, a labor union, the Knights of Labor, reached the height of its power, with more members than any other labor organization in nineteenth-century America. Engels described the Knights as:

An immense association spread over an immense extent of country in innumerable ‘assemblies,’ representing all shades of individual and local opinion within the working class; the whole of them sheltered under a platform of corresponding indistinctness and held together much less by their impracticable constitution than by the instinctive feeling that the very fact of their clubbing together for their common aspiration makes them a great power in the country; a truly American paradox clothing the most modern tendencies in the most medieval mummeries… The Knights of Labor are the first national organization created by the American working class as a whole; whatever be their origin and history, whatever their shortcomings and little absurdities, whatever their platform and their constitution, here they are, the work of practically the whole class of American wage-workers…

The Knights chose to use their unprecedented size and income to pay their officers and hire staff on a far larger scale than any previous labor union. Prior to the Knights, labor organizations paid their officers poorly or not at all, and almost never hired staff. The Knights’ decision to establish the first real union bureaucracy was something of an experiment, one that had unforeseen results.

In 1873, the economy crashed again. Widespread unemployment made it easy for employers to replace fired union members, making nearly all strikes fail and destroying most labor unions. Founded in 1869, the Noble & Holy Order of the Knights of Labor was one of the few unions to grow during the 1870s. It was able to do so partly by relying on extreme secrecy to avoid firings, and also by using sub-cultural appeals to attract and retain members even when the union could not deliver any concessions from employers. In its early years, the Knights resembled an anti-capitalist version of the Freemasons. They were founded in Philadelphia and did not spread outside the city until 1873. Initially they had no national structure or organization, only local and, later, district assemblies. After they grew to approximately 10,000 members, the Knights decided they needed a national structure and held a founding convention in January 1878. Unlike previous unions, the Knights were open to workers of all crafts. They believed the unification of labor into one big union would be a more effective means of checking “great capitalists and corporations.”

Initially, the Knights used paid labor sparingly. Terence Powderly, who would lead the Knights in their heyday, wrote of his early experience in the Knights in Scranton, “We had no organizers, paid or otherwise. Every member carried a message to his fellows, and in a short time assemblies [locals] began to grow and flourish all through the coal fields.” In 1877, the number of KoL local assemblies in Scranton grew to the point where they decided to organize a District Assembly. The delegates to the district chose to elect a paid organizer, Joshua R. Thomas, who was to “give his whole time to the work.” To pay his salary, delegates voted to require every affiliated local to pay one cent per member per month to the district. It is tempting to view Thomas as an early example of a staff organizer; however, as he was elected not hired, he was really a paid officer, not staff (officers are elected; staff are hired).

When the Knights established a national organization they included a mix of paid and unpaid officers from the start. Initially their national officers included a Grand Master Workman [President], Grand Worthy Foreman [Vice President], Grand Secretary, Grand Assistant Secretary, Grand Treasurer, five members of the Executive Board, and many ceremonial positions that played a role in their subculture. The term “grand” in all these titles would later be changed to “general” in 1883.

The Knights’ constitution required officer pay to be set by their convention, which they called the General Assembly. In 1878, it set pay at $200 per year (equivalent to $5.3K in 2021 dollars) for the GMW, $800 per year (equivalent to $21K) for the Secretary, and $50 per year (equivalent to $1.3K) for the Treasurer. In 1879, the GMW’s pay would be doubled to $400. The union also covered expenses. All other positions were unpaid. Officers typically had other jobs in addition to their union duties.

Unlike the Knights of St. Crispin, the Knights of Labor had paid organizers. Most organizers were commissioned by the Grand Master Workman; in locations where a District Assembly existed, he usually commissioned whoever the DA recommended. The founding 1878 General Assembly voted to give the GMW, as well as the District Master Workman of each District Assembly, “power to authorize the organizer of any [local] Assembly to retain so much of the charter-fee as may be necessary to pay his actual expenses in organizing said Assembly.” In the 1880s, they would adopt a more generous policy, voting to pay organizers up to $6 ($160 in 2021 dollars) per local assembly organized, in addition to mileage and expenses. The responsibility for paying organizers lay with the new local they organized, not with the international. In the early 1880s, the Knights also employed four people as organizers at large, who were expected to reach areas distant from a current local. These positions were paid a salary of $15/day, but were abolished 1883 because there were no longer parts of the country distant from a local. Although the KoL employed paid organizers, they were primarily geared towards setting up new locals — organizing additional workers in the jurisdiction of an existing local was the responsibility of the officers, or of the members themselves. Most organizers had another job and did organizing part-time, although it would have been possible to make it a full-time job in 1885-86, when the Order was expanding rapidly.

Early 1880s

Terence Powderly was initially elected Grand Worthy Foreman, and then Grand Master Workman in 1879. Originally a machinist, Powderly was elected mayor of Scranton in 1878 on the ticket of the Greenback-Labor party, a left-wing third party. From 1879 to 1884, he simultaneously served as mayor of Scranton, leader of the Knights of Labor, and Corresponding Secretary for his District Assembly (the latter position was unpaid). He had started studying law but gave up his studies to focus on the labor movement upon being elected GMW. During this time, he derived most of his income from his mayoral salary, which paid $1,500 per year (equivalent to $39K). Powderly claimed he used his union salary to pay his expenses as GMW and “devoted what was left to the building up of the Order.” Additionally, he also worked on a tea & coffee venture with his brother-in-law for a year, and briefly worked in a grocery store. There were multiple proposals brought to the General Assembly to raise the GMW’s pay, but Powderly opposed them all, even threatening to resign if they passed, because he did not want the additional work and responsibilities that came with the pay boost. Until 1884, leader of the largest labor union in the country was not a full-time job, let alone a career.

Although Powderly stymied attempts to raise the GMW’s pay, the General Assembly used its additional income from a growing membership to gradually expand the Order’s use of paid officers. In 1880, it increased the Grand Secretary’s annual pay from $800 to $900, and made the position of Assistant Grand Secretary a paid one, with a salary of $750 (equivalent to $19.5K). In 1882, they started electing a co-operative board to oversee the Order’s efforts to promote and organize cooperatives (co-ops could directly affiliate with the union), but every officer on the board was unpaid. They also further increased the annual salary of the Grand Secretary and Assistant Grand Secretary to $1,200 each (equivalent to $31K), and increased the Grand Treasurer’s pay to $100 (equivalent to $2.6K).

In 1883, the General Assembly doubled the GMW’s salary to $800, which was a compromise from an initial proposal to raise it $2,000. They also started relying on office staff by abolishing the position of Assistant General Secretary and authorizing the General Secretary to hire a chief clerk and pay him $1,000/year. Regular clerks, also hired by the Secretary, were paid $12-$18 per week, which would work out to $16.3K – $24.5K annually in 2021 dollars if they worked fifty weeks a year. The GA made the secretary of the General Executive Board, previously unpaid, into a full-time job paid $1,200 annually. They also started paying the General Statistician $300; this position would be abolished in 1885 and its responsibilities transferred to the General Secretary-Treasurer (the offices of secretary and treasurer would be combined and split apart several times).

In 1884, Powderly ended his political career and decided to work for the Knights of Labor full-time. The General Assembly increased his salary to $1,500, matching what he had been paid as mayor. It also gave him additional responsibilities, including a requirement that he spend a total of at least 16 weeks per year in the field, equally divided between different parts of the country. Powderly would continue to live in Scranton rather than moving to the Order’s headquarters in Philadelphia, but traveled frequently. This GA also made both the General Master Workman and the General Secretary-Treasurer members of the General Executive Board.

The slow growth of paid officers and administrative staff was made possible by the steady growth of the Order, which went from approximately 10,000 members in 1878 to roughly 100,000 in 1885. The decline in unemployment beginning in the late 1870s, as well as the impetus provided by a wave of riots and strikes by non-union workers in 1877, created a climate favorable to the growth of organized labor. At Powderly’s urging, the Knights also adopted a series of policies that facilitated its growth. It scaled back secrecy and sub-cultural elements, making it easier to recruit workers not interested in freemasonry. It also began organizing black workers and, after a group of female shoe workers applied for membership, women workers.

Height of the Knights

In 1885, the Knights won a series of strikes against the railroad mogul Jay Gould, prompting workers to join the union in droves. Officially, membership went from 103,335 to 702,924 in the space of a year, although many historians estimate that its membership actually reached one million. Such rapid growth created administrative difficulties for the union’s staff and leadership; they received more charter applications and dues money than they could process. New members often were not well informed about the Order, and there were several hundred cases of organizers signing up new members with jobs that were prohibited from joining the union, including lawyers, bankers, and Pinkerton detectives. The GEB thus decided to suspend all new organizing for forty days and instructed organizers to focus on educating current members instead. Their organizers only got paid for organizing new locals, not for educating current members, so they continued organizing but held on to their charter applications until the forty days were up and then sent them in all at once.

The Knights chose to use their sudden influx of money and members to expand their staff and pay most of their officers, giving some of them salaries substantially higher than the average worker’s pay. At a special session of the General Assembly, held in spring 1886 to respond to the rapid growth of the Order, they voted to increase the size of the General Executive Board by six people and to adopt a rule that “no organizer shall be permitted to organize two or more Assemblies in any one day,” effectively putting an upper limit on organizer income. It further instructed the GMW to appoint an examining organizer in each state, to act as supervisor over the other organizers, with pay rate left up to the GEB.

At the regularly scheduled General Assembly, held in Richmond in October, they voted to raise the General Master Workman’s pay to $5,000 per year, the equivalent of $150K in 2021 dollars. That is an unprecedented salary – vastly more than any previous labor leader – yet it is still not as high as what the AFL-CIO currently pays its executives during an era of decline for organized labor. The GA also voted to set the pay for General Secretary and General Treasurer at $2000/year each (equivalent to $56K) and pay GEB members $4 per day. The Knights then spent $50,000 (equivalent to $1.4 million) to purchase and repair a headquarters building in Philadelphia.

The Richmond session also voted to create a full-time salaried women’s officer, initially titled the General Investigator of Women’s Work. The position was proposed by the women’s committee, which had been elected by the 1885 GA and consisted of several unpaid female Knights. The GIWW was a full-time job that paid about the same as GEB member. The GA elected Leonora Barry to the office and would consistently reelect her unopposed until 1890, when she chose not to run for reelection. In 1887, the GA abolished the women’s committee, replacing it with a Women’s Department headed by the General Investigator, giving her greater authority to hire staff and making her position a general officer on par with other international KoL leaders. In 1888, at Barry’s request, they changed her title to General Director and Instructor of Women’s Work. Barry’s decision not to run for re-election in 1890 was partly the result of harassment by General Secretary-Treasurer John Hayes, and had the effect of mothballing the department, ending female participation in the highest levels of the Order’s leadership.

As the KoL reached its height in 1886, employers began organizing a counter-offensive against it. They founded employer associations which coordinated a series of lockouts against the union, eventually defeating it. The government also engaged in repression against the Order, deploying the state militia against the Great Southwest Railroad Strike and massacring Knights in Milwaukee and Louisiana. The union’s decline caused a rise in infighting, increasing criticism of Powderly and other international leaders. Membership declined to roughly 100,000 by the end of the decade, and dropped further after losing the New York Central Railroad Strike of 1890. It continued to bleed members for the remainder of its existence.

Changes in the Union

The transformation of the Knights from a few moderately paid officials with a small staff into a real bureaucracy with well-paid leaders changed how the Order operated. Allegations of corruption became more common; some of those allegations were true, others were not. Internal democracy declined. Salaried officers doubled down on the organization’s cautious and conservative tendencies, bringing it into conflict with a more militant rank & file.

Leaders did more to insure they retained their well-paid jobs, including resorting to less than democratic measures. The terms of several offices were lengthened to two years while Powderly formed a series of shifting coalitions to stay in office. Using various pretexts, his allies expelled several prominent Powderly critics from the Order and manipulated the credentials committee to gerrymander the composition of the General Assembly by selectively denying delegate credentials to their enemies. In 1889, Powderly and several other leaders, including Secretary-Treasurer John Hayes, formed a 19-person secret society named The Governor to maintain control over the union.

Joseph Buchanan, who was one of the main organizers of the 1885 strikes against Jay Gould, wrote in his autobiography that “General Master Workman Powderly seemed entirely to lose his head immediately following the Richmond session.” Powderly sent out circulars denouncing strikes for eight-hour days and forbidding local assemblies from collecting financial aid for the Haymarket defendants. In 1888, Powderly told the General Assembly, “The chief trouble with our Order is because of the lack of one-man power… A pandering to ignorance by some has given rise to the impression that the man who railed against one-man power was a friend to the masses. No greater mistake was ever made.”

Left-wing Knights criticized the new practice of paying officers significantly more than their members on the grounds that it perpetuated economic inequality. In his newspaper, the radical Burnett Haskell cited an article written by Powderly discussing poorly treated workers and asked of Powderly, “Is it not a fact that the wages of these women did not average 40 cents a day, that they paid dues into the Knights of Labor, and do you think that you are justly entitled to receive from their contributed many mites fourteen dollars a day while they still live in that Hungry Hell?” Powderly treated Haskell’s (numerous) questions as a kind of harassment, but General Secretary Charles Litchman defended high officer pay at the 1887 General Assembly:

I have given service which in any other direction and for any other than the cause of labor would have yielded me a far larger compensation. When among other unjust and insulting attacks I have been taunted with the exorbitant salary paid I have wondered if any corporation in the land would requite so poorly the work done by your General Officers. A man who accepts official position in a labor organization at once makes himself the target for all the attacks that envy, malice, jealousy and hate can direct against him… That these attacks should be made by the agents of monopoly is not strange… But when these attacks… are seconded and encouraged and ammunition for them furnished by malignant members of our own Order he who holds official position may be pardoned for sometimes feeling that the organization he serves is too ungrateful to properly appreciate the sacrifice made.

Underlying this argument is the principle that labor leaders ought to be paid by unions for the services they provide the labor movement. That principle is similar to arguments used by the Knights and most other unions to argue for increasing the pay of their members: they do valuable work and thus should be paid the full value of their labor or at least a fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work. The radical critique of high officer salaries was also based on a common unionist principle: that economic inequality is bad and we should strive to avoid a situation where a small percentage of the population makes substantially more than the majority. When the Knights became an employer it set these two principles in conflict with one another: it had to choose between paying its employees well and maintaining equality between its members and employees. The General Assembly chose the former option.

The salaried international leaders of the Knights were often more cautious than rank-and-file members when class conflict reached more intense points. During a strike in Chicago’s stockyards in fall 1886, Powderly sent a message ordering the termination of the strike, telling KoL officials in Chicago, “if men refuse take their charters. We must have obedience and discipline. By order of General Executive Board.” At the same time, Knights at the Langdell textile mill in Philadelphia went on strike, demanding higher wages and the firing of a supervisor they claimed was “tyrannical” towards female workers. After strikers assaulted scabs, the conflict escalated into a series of additional strikes and lockouts, with the employer association threatening a city-wide lockout. Several international KoL leaders, including Powderly & John Hayes (then a GEB member) went to Philadelphia to negotiate with employers, where they agreed to set wages by arbitration, drop all other demands, and terminate the strike. Many local Knights felt sold out. Female Knights in Langdell wildcatted rather than return to work, and persuaded all of their male co-workers to do the same. Langdell’s owner gradually replaced all of the strikers and stopped negotiating with the Order. Most international KoL leaders felt that strikes were generally ineffective, unnecessarily exposed the union to repression, and endangered its finances. The transformation of the Knights into an employer with a hierarchy of staff and long-term officers paid more than its average member caused it to have less in common with the workers it was founded to fight for.

Corruption and the End of the Order

As the Order’s finances declined in the early 1890s, General Secretary-Treasurer John Hayes became enthusiastic about investing in companies and get-rich-quick schemes, putting union money into them and encouraging other officers to invest their own money. Powderly initially went along with this and even invested some of his own money, but then told Hayes to sell his shares and stop using Knights’ funds for these financial schemes. Hayes quietly disregarded the direction and began shifting funds from accounts earmarked for specific purposes into trust funds under his control, which he spent on whatever he felt like. He also started spying on other officers, stealing their mail and having his staff keep tabs on them.

Hayes had a sexual relationship with one of the Knight’s staffers, the stenographer Maggie Eiler, who he also used to spy on other officers. By the end of 1892, she had started telling other KoL officers of Hayes’ actions, including embezzling and misappropriating funds, prompting him to threaten her. In a January 1893 letter, Hayes wrote to her:

You and me can’t be anything but friends for the reason that you know too much about my business. You see, I am still G.S.T., and I intend to remain G.S.T. in spite of Powderly and the entire General Executive Board trying to get me out… I once told you I had the power to make you tired of living, didn’t I? Well, after [what] the d[am]n Board has done to try and get rid of me don’t it prove that I am more powerful than they are? Keep my business to yourself… By G[o]d, I trusted you with matters I wouldn’t trust anyone else with, and then you turn around and tell the d[am]n Board everything you know. It’s all right; no harm done. You see I am still G.S.T. and intend to remain G.S.T. till I get d[am]n good and ready to step down and out… I was a good fellow as long as I let them into money-making schemes but as soon as I shut down on them they had no further use for me.

Eiler turned this letter over to the GEB.

Hayes filed a set of fourteen charges against Powderly and a civil lawsuit against the Order, alleging financial and other misconduct, as well as exposing the existence of The Governor. Powderly responded by suspending Hayes from membership. At the 1893 General Assembly, John Hayes and his allies stopped protecting Powderly and allowed the left to make a direct attack on his position. One delegate, the Marxist Daniel DeLeon, campaigned to vote Powderly out of office, declaring “The K o L under you stands in the way of progress. We have to get rid of you and supplant the order with a more radical form of organization.” Nonetheless, the GA reelected Powderly by a small margin. Furthermore, the GA charges committee completely exonerated him, finding that the union actually owed him $3,200 in back pay. However, the GA also reelected John Hayes to GST and elected an anti-Powderly majority to the GEB. Faced with these results, Powderly resigned. This was not the first time Powderly had resigned — in the past, whenever he resigned, the GA would back off and offer Powderly a compromise to get him to remain as GMW. This time, they (narrowly) voted to accept his resignation and elected James Sovereign the next General Master Workman.

The new leadership of the Knights moved to ensure Powderly could not come back into office. They redrew the borders of Scranton’s District Assembly for gerrymandering purposes, and suspended Powderly’s local assembly. At the 1894 General Assembly, the credentials committee denied seats to fourteen pro-Powderly delegates. The Assembly then proceeded to expel Powderly from the union on the pretext that he had refused to hand over the Philosopher’s Stone Degree, which was important to their subculture, after leaving office. Powderly would later be readmitted at the turn of the century, after settling a wage theft lawsuit against the Order for $1,500, but he would never be very active in the union again.

Powderly’s defeat did not mean the victory of the left. In 1895, the General Assembly rejected Daniel DeLeon’s delegate credentials, prompting him and his allies to leave, reducing the Order’s membership from 30,000 to 17,000. Over the next decade, the Knights repeatedly split, with corrupt leaders of each faction claiming to be the legitimate officers and filing lawsuits against each other for ownership of the Order’s property and bank account. In 1898, the KoL began allowing workers to join and pay dues through mail order in order to boost their declining dues base (previously one could only join in person through an organizer or local), but this resulted in a dispersed set of paper members rather than any real organizing. After another split in 1902, John Hayes emerged as the legally-recognized General Master Workman of the Knights of Labor, its final leader. He disbanded the international in early 1917, after the money ran out. A small number of KoL locals continued to exist as late as the 1930s.

The Knights’ experience shows some of the potential pitfalls of unrestricted growth of paid officers and staff. Paid organizers faced a conflict between their financial incentives and what was best for the Order, leading them to organize unsustainable growth even when ordered to pause by the international leadership. Bringing in an unprecedented amount amount of dues money and legitimizing the principle that labor leaders deserve to be paid several times what their members make created an environment where a greater level of union corruption was possible. Earlier labor organizations did not accept that labor leaders should be paid substantially more than their members, and most could not have afforded to do so if they wanted to.

In its first few years, the Knights’ policies on paid officers and staff looked similar to Reconstruction-era labor unions: the Secretary was a full-time paid officer, but other officers were part-time or volunteer positions. Growth of paid labor in the union occurred in the wake of the growth of its membership and dues income. The Knights not only broke with earlier unions in employing paid labor on a large scale, it also paid its top officers substantially more than its members and employed a hierarchy of staff.

The Knights’ experiment ended in failure but it foreshadowed similar policies that would be followed by later labor unions. Although the Knights established a full-fledged bureaucracy with salaried officials, it was in the craft unions affiliated with the American Federation of Labor that union official became a real profession. The Knights simply did not last long enough to transform union official into a viable long-term career, but the American Federation of Labor had a nearly seventy-year lifespan. Part three in this series will trace the genesis of union professional in the AFL in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries.

Robin J. Cartwright is a former labor historian, with a PhD in late-nineteenth century U.S. working class history. He is a member of the IWW and a former elected department representative of the Communication Workers of America.