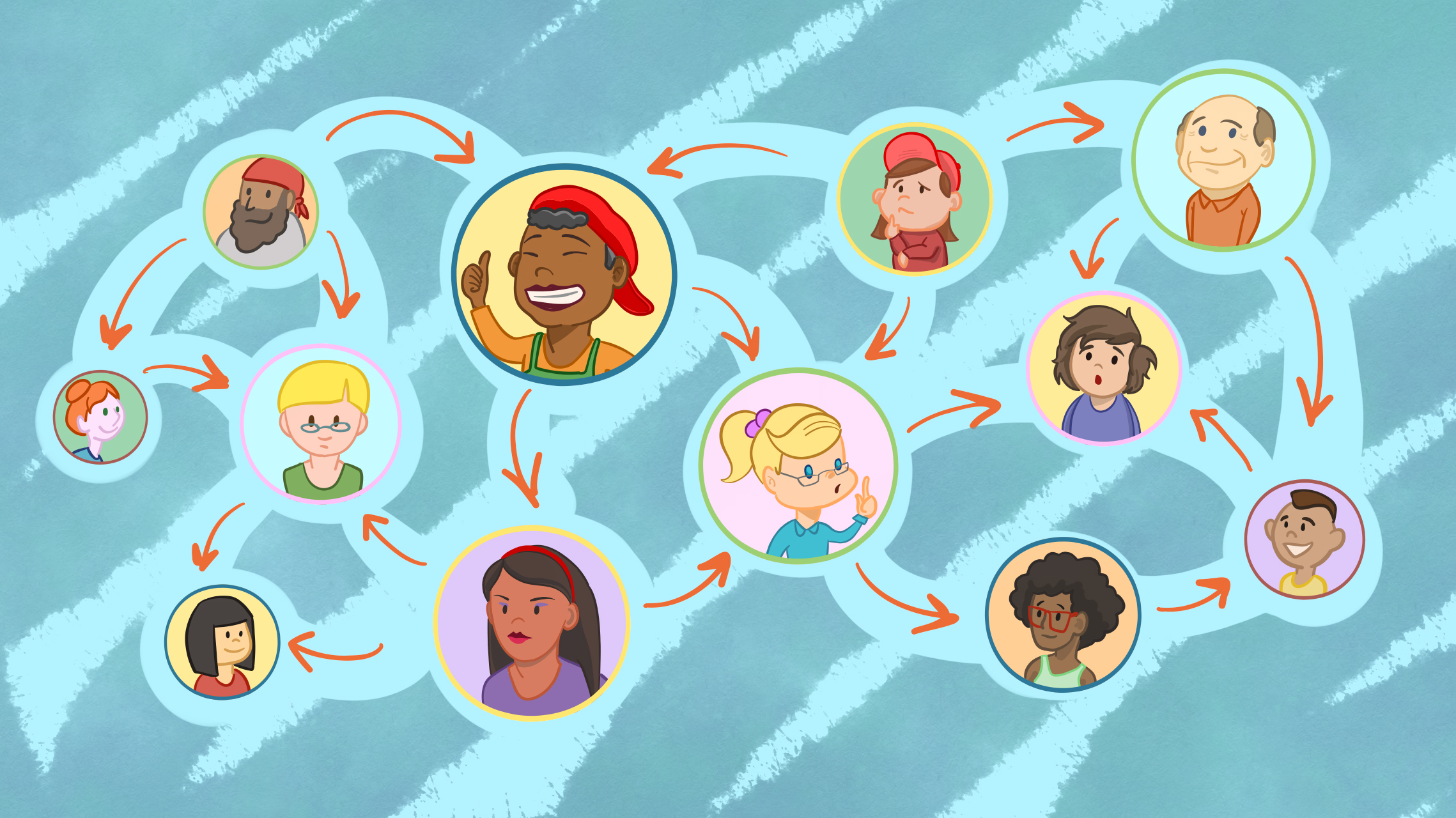

Nick Driedger argues for the importance of delegating union tasks. Image © Emé Bentancur, 2022.

The work of the union never ends. As soon as you start being seen as effective by your coworkers, it seems like the workload only goes up. The only way to get on top of this is to delegate work.

Delegating, like everything in organizing, is a skill — it’s something you practice, and the more you do it, the better you get at it. The surest sign you are becoming a veteran organizer is that your first move in any situation is to task work to other people and explain how it is done.

Not delegating leads to a smaller and smaller circle doing more and more work, which leads to burnout. The active few find themselves really busy and yet the campaign isn’t really advancing. Once this dynamic sets in, they start to blame each other (and get angry at the membership).

The more you delegate, the more you can replace yourself, and the larger a pool of people there is to take on the tasks. The union or campaign becomes more competent with a greater number of competent people overall.

Delegating means assigning tasks to others but that doesn’t mean it is any less work for the organizer. In fact, delegating is more work at first, because you are simultaneously developing people while still making sure (from afar) that tasks get done. Building up other people takes more effort than just doing a task yourself. After doing that enough, however, your own workload goes down a bit, and eventually you can take that step back. And that’s good, because organizing is something you should be able to step back from without it collapsing.

How to Delegate

I remember being a young shop steward at Canada Post and telling an older veteran about all of the problems in my local, the apathy of the workers, the arrogance of management, and the fact that no one was circulating information from the local to the floor.

She smiled and walked over to a stack of bulletins and put them in my hands, and told me I should go to work 20 minutes early tomorrow and drop a bulletin off at every case, then use my break to talk to one row of letter carriers a day until I had covered the whole depot. She took my complaining and turned it around on me. I was already agitated but she made me put my money where my mouth is.

It does not take much for a conversation about work to turn to complaining; organizing is the art of taking that energy and directing it somewhere useful.

Delegating has a few components to it:

Always start with Agitation. If a coworker approaches you with an issue, rile them up and then transform that into a task. If they’re not already approaching you, go to them. Ask a lot of questions, until you find out what they care about. Make them feel heard and make the issue feel urgent. Then task them with work related to that, even if it’s asking other coworkers if they have the same issue.

Trust others. This work is not just for people who “get it.” You can’t delegate if you don’t respect someone’s abilities, and if you don’t respect their abilities, get over yourself — organizing is not rocket science and if someone is smart enough to be doing a job alongside you, they can organize it too. Trust also builds over time, and with the trust you build, you can start giving tasks that are more ambitious but also more outside what that particular member cares about. That way they become more invested in the organization and not just in the demands that affect them.

Break the job down into manageable tasks. Think about what you are trying to get someone to do and take each step and spell it out. What seems like a thousand mile journey seems more manageable when you take it one step at a time. The bigger your organizing goal and the more workers being organized, the more tasks there are to reach it, and the more hands are needed to do the work.

Delegate delegating. Delegating starts with not doing the work for people. But it has to move quickly to also making sure other people are not taking everything on themselves. It’s okay to intervene and tell some that they have too much on their plate and suggest someone else does it. It’s also okay to tell someone that something that you want done should not be done by them. If you need to, role play and plan how you are going to ask someone to do something. Practice it — it’s not easy for everyone to ask someone else to do something but it’s a skill people in a campaign need to learn if the campaign is going to grow.

The bigger the struggle, the more logistics matters. Planning out the different tasks and delegating on a large scale requires coordination. This coordination usually happens through a committee, and the bigger the job the more the work gets pushed out into sub committees. Tasks can be tracked through spreadsheets and regular check-ins but if you are going to have levels of committees you are going to want to decide what decisions are made at what level. Bylaws, minutes, and reports all become very important for this process.

Follow Up. Did someone fail to do a task? Call them and ask what happened, dig deeper than their first answer. When in doubt go back to agitation — get them talking about their problems at work again. Sometimes you have to hand the work off to someone else to get it done; people are busy. Sometimes it just won’t get done and that’s okay. A lot of us are the kinds of people who just find it easier to do things ourselves: resist that temptation. Delegating isn’t just about pushing the work out, it’s also about building people up so find a new task that may be a better fit for that person. If the job doesn’t get done that’s a problem but a worker losing confidence in their ability to do something about the problems they face is a bigger problem. It’s longer and harder to get people to do things on their own but it’s the only way people gain the confidence to act independently.

Opportunities to delegate

Every job that needs to be done, including figuring out what jobs need to be done, is an opportunity to delegate.

A lot of radical unions back in the good old days rotated the chair of the meeting and minute-taker. If everyone needs to learn the rules of order, everyone is on an even playing field. Tasks like booking the room to meet, setting up the online meeting space, or sending out the announcement email are all great jobs for someone just getting involved.

Coordinating making the signs for a picket, coordinating rides to and from an event are all great jobs to delegate because they get people to build relationships. Most people find talking to strangers hard but it gets easier the more you do it.

Workshops and trainings are also a great way to divide up tasks and get different people to do the work. If lots of people are counting on it getting done make sure you check in lots and have a backup to step in if someone has something come up.

Public speaking is always a good job to rotate; make sure you have people help prepare the speech together. Coffee break meetings or parking lot meetings are where almost every great trade unionist learned to do public speaking. Switching up who speaks builds everyone up and also lets you give each other pointers.

Why people don’t complete tasks, and what to do about it

In general there are really only a handful of reasons that people did not follow through.

You didn’t delegate properly. If you call someone up and try and drop something on their lap at the last minute they are not going to have the time and probably resent you for doing so. If you give someone a really long time to do something and never check back in they are going to forget about it and feel abandoned. You don’t delegate because it’s less work for you; you delegate because it means work gets done by more people. Checking in with the people you delegate work to every week or two is reasonable.

The task was not clear. As an organizer sometimes people just don’t understand what you are asking and sometimes the task isn’t as obvious as it looked at first. They don’t want to argue with you so they just agree because it’s easier than feeling dumb by asking a bunch of questions. When that happens the main problem you need to address is them feeling like you care what they think, then you can circle back to what needs to be done.

Something came up. People have lives and children or eldercare; maybe they have another job or their car broke down. Check in with them, ask them about how they are doing and try again. Being patient with people and developing a strategy that lets you be patient with people by not imposing unnecessary deadlines on the work makes this a lot easier.

The person didn’t care about it as much as you did. You’re the one with the big ideas, you’re the one who wants to change the world. You either need to make people care about this as much as you do (and this is hard and takes time and a lot of trust) or work on what the workers care about (this is much easier). What is revolutionary about the working class is not that they are all potential converts to your cause; what is revolutionary about them is that they can only improve their lives in this world by working together in solidarity and that creates a new world. So what do you do when someone doesn’t follow through and there is no one to pick up the job? Wait and listen. Either people just aren’t ready yet or the issue that will push the organizing forward is something you haven’t identified yet. Never let the urgency we all feel about the need for a better world get in the way of letting it happen.

Delegating builds the kind of unionism we want

The biggest question people have about direct action-based unionism is: how does it scale? They can understand the need for militancy and they see lots of examples of small groups taking action and winning but the larger groups, big militant unions, are treated as if there is a certain kind of magic. There isn’t. A few factors go into big militant organizations but the biggest one you can actually control is the culture of having the work done by the rank and file. This doesn’t necessarily mean there is no role for officers and staff but it does mean the spotlight should be on the workers doing it themselves.

There is not a job in the union that should not eventually have a member directing the work and knowing how to do it. This is an important part of the political content of our kind of unionism: if workers are going to run the world they need to start by running their own unions.

Nick Driedger is the Director of Labour Relations and Organizing for the Alberta Union of Provincial Employees and a frequent contributor to Organizing Work.