Marianne Garneau reviews Feminism for the 99%: A Manifesto.

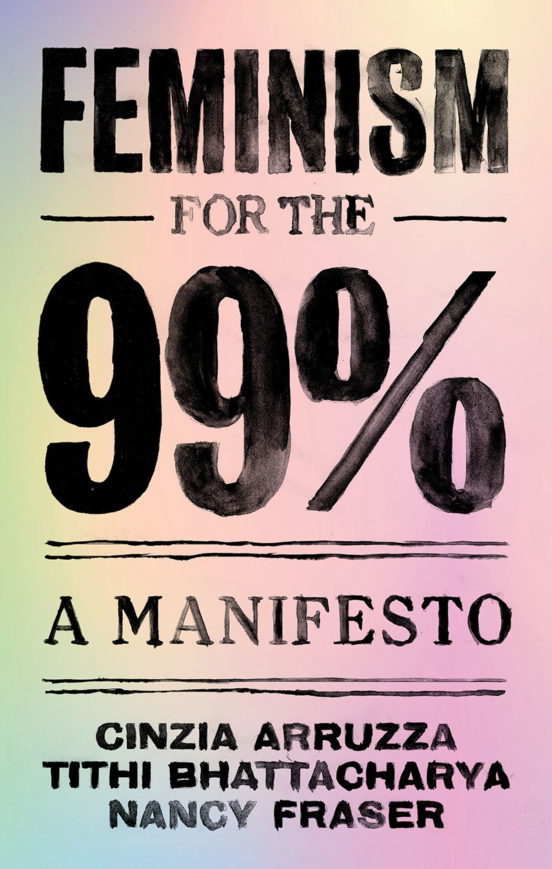

In a new book, Feminism for the 99%: A Manifesto (Verso, 2019), Cinzia Arruzza, Tithi Bhattacharya and Nancy Fraser put forward the “women’s strike” as the much-needed reinvention of the strike tactic.

The authors are also the organizers of the “International Women’s Strike.” Originally inspired by large-scale protests in Spain (against sexism and patriarchy), Argentina (against violence against women), and Poland (against a total abortion ban), the IWS involves simultaneous one-day demonstrations in cities around the world on March 8, as well as smaller events throughout the year. Although March 8 has been celebrated as International Women’s Day for some time, the International Women’s Strike dates to 2017. With the IWS entering its third year, this book is the authors’ and organizers’ mature reflection on the tactic.

I am reviewing this book as a contribution to the area of “critiques of the strike” – I launched this site with such a critique (written by a woman), and I am very much interested in these debates, and in rethinking the strike in general.

The women’s strike, the authors of the Manifesto say, is a new form of class struggle, and seemingly the only one able to address the multitude of oppressions women face, from sexual harassment and violence, to the erosion of reproductive rights, to economic exploitation, to the disappearance of the social welfare state.

Most acutely, they argue, the typical workplace strike does not reflect the fact that women’s exploitation and suffering under capitalism doesn’t just come from paid work. Women not only work for a wage, they generally bear the responsibility for the entire system of unpaid work that reproduces society and sustains capitalism – the “people-making” reproductive labor that undergirds “profit-making.” Women reproduce the workforce by having babies and raising children, they feed and care for working adults so they can show up for their shifts, they maintain households and families and communities.

The typical union strike, the authors of the Manifesto argue, only fights on one terrain of women’s struggle, and therefore cannot address the multifaceted nature of women’s oppression and exploitation under capitalism, or, by the same token, the various dimensions (political, ecological, social, economic) of the current capitalist crisis. The women’s strike – also sometimes called “A Day Without A Woman” — is a new way to strike that can address all of these, by “democratizing and expanding [the strike’s] scope.” It “anticipates a new phase of class struggle” where we no longer have to choose between economic issues and social issues, between Marxism and identity politics.

Unfortunately, the “women’s strike” is built on two shaky premises: a needless hostility to labor unions, and a total elision of what it would mean to strike effectively in the area of reproductive labor.

Hostility to labor unions

Again, I am sympathetic to reevaluating strikes, for all kinds of reasons. They’ve become top-down events, largely symbolic and not really rooted in worker power. Jane McAlevey has pointed this out, and argued in favor of a revival of the true, economic strike. As my author put it, however, even when they are a bona fide withdrawal of labor power, they don’t deepen workers’ control of the productive process, but literally and figuratively place workers outside of the workplace. Strikes, whether symbolic or economic, are usually stage-managed by union bureaucracies, who are removed from the rank-and-file, and perennially choose to consolidate their own power and their own control over the workplace, rather than allowing the ranks to run amok confronting management.

So yes, strikes have their problems. But the authors of the Manifesto aren’t advancing an effective alternative. They’re not even advancing a useful criticism of labor union strikes, but a misplaced hostility to them, as a kind of backward-looking territorialism that excludes women:

Making visible women’s power, [women strikers] have challenged labor unions’ claim to ‘own’ the strike. Signaling their unwillingness to accept the existing order, feminist strikers are re-democratizing labor struggle, restating what should have been obvious: strikes belong to the working class as a whole—not to a partial stratum of it, not to particular organizations.

As though unions chauvinistically exclude women from struggle.

The authors frame labor unions as mostly irrelevant to the current struggle because their power and their membership have declined with the decline of manufacturing, and irrelevant to women’s lives in particular because women don’t work in manufacturing jobs, but in low-grade service sector jobs.

There are numerous problems with this story. In the first place, black women, for example, are actually overrepresented in unions relative to the general workforce. The authors of the Manifesto deride those whose image of the working class is “straight, white men” but that is clearly their image of the union member: the white auto plant worker of yesteryear, as opposed to the Hispanic or black woman working in a public sector job today, for a city or hospital or university.

Second, this is a misleading story of union decline. There is no inextricable link between manufacturing and unions (this is a canard of both the left and right). Unions were fought for in that sector, which dominated the labor market in the middle of the 20th century. Before they were organized, manufacturing jobs were poorly paid and had no prestige. The decline in unionization rates over the last 40 years reflects a political battle which labor has been losing, even at times when the number of manufacturing jobs (in the US) has increased. There is nothing fundamentally low-wage or low-prestige about service jobs; the problem is that they haven’t experienced the same unionization rates, although those efforts are on the rise, and they should be encouraged, not sidelined as parochial or irrelevant for addressing women’s multifaceted oppression.

Here’s why: work is a place where women have power, insofar as they have their hands “on the levers of production” – yes, even in a service-sector job. Where women work for paychecks, they have the ability to withhold their labor. That is leverage. That is why the gender pay gap is much smaller among unionized workers than non-.

That power can be leveraged for the particular issues women face in the workplace. To give a minor example: women I helped organize at a restaurant now have a lactation room for when they return to work after having babies. That is unheard of in the restaurant industry in New York, even though it is mandated by law. The owner had refused, for years, to provide such a room, even after being sued. There is one there now because these women have organized, and brought real pressure on the employer through things like strikes and work refusals, and the boss is quite frankly terrified of them.

Is the International Women’s Strike a strike?

For its part, the International Women’s Strike cannot seem to decide whether it is a labor strike or not. It goes to great lengths to differentiate itself from those staid, “merely economic” workplace strikes, but it also consciously brands itself as a strike, rather than a protest. The argument goes: it is a “strike” because, if you are there, you are perforce not at work, and not at home performing domestic labor. But it certainly looks more like a protest: the events are generally brief rallies towards the end of the typical working day, and more to the point, the IWS organization doesn’t develop workers’ capacity to take coordinated, collective action. Instead, women are simply invited to participate, and some teachers and university professors, assessing their own risks, have elected to do so. (To clarify, I am not a stickler that “strikes” can only take place in relation to workplaces.)

Let me put it another way: if IWS is a strike – and there is indeed, in the promotional material, an invitation to workers to leave work – it is a not a very well-organized one. Telling workers not to show up to work, without first building the protective umbrella of collective action, which can only be marshaled by building relationships of trust between workers in the same workplace, is terrible organizing advice. Only when multiple workers are in lockstep can they, and not the boss, decide whether the workplace is to be shut down that day (unless they enjoy the protections of tenure).

If, on the other hand, the Women’s Strike is just an open invitation to show up if you can, then it’s not a strike but a protest. And that’s ok. Protests are nice, especially ones coordinated simultaneously around the globe. I for one plan on going.

Unable to marshal an actual strike (and that’s understandable: such a task would be gargantuan), the organizers of IWS declare that workplace strikes are outmoded anyway. And thus elevate a weakness of IWS to a virtue.

Action without a demand

If the International Women’s Strike is a strike, it is one that has removed the very things that make them meaningful and successful: the leveraging of real power to advance particular demands.

Just as the IWS doesn’t really engage in a withdrawal of labor, it doesn’t really have specific objectives. The goal seems mostly to be to draw attention to the myriad issues faced by women, from environmental collapse to colonial oppression, and relate these problems to capitalism itself. But it’s not clear the women’s strike is actually asking for anything in particular, from anyone in particular – other than “an end to all of these things.”

The authors argue that what is needed – and I agree – is a massive reorganization of social relations. They back away from describing what we are struggling for: “our Manifesto does not prescribe the precise contours of an alternative, as the letter must work in the course of the struggle to create it,” but they do say that it cannot be accomplished through legal reform.

One even gets the sense that they are expressly saying that they will worry about actual change later: “we seek to build an anti-capitalist force that is large and powerful enough to transform society.” That’s rather vague, and seems to hint at building a constituency or coalition now, with transformation to come down the road.

All of this reminds me of a tendency on the left right now to say, quite seriously, that our uncompromising and unrelenting goal is and must be full communism. Free, universal childcare in the United States, on the other hand? Nah, not realistic.

But concrete steps forward, realized one objective at a time, are not only what improves people’s lives, they are a form of accountability, and a way of building class power. If there’s nothing you’re specifically trying to achieve, no one can hold you accountable for not achieving it. And if you don’t take action towards measurable goals, you don’t grow any stronger.

When I train workers in direct action unionism, I emphasize that direct action is not just a matter of deploying cool tactics, like banner-drops and demonstrations and work refusals. Direct action is only meaningful if it takes place within a whole horizon of strategic considerations: a grievance or problem to be addressed (something winnable), a concrete demand to fix it (so you know that you’ve won), with a deadline attached, a target for that demand (someone who can deliver on it), a well-chosen tactic, thoughtfully chosen participants, and an escalation plan if your demand is not met by the deadline.

The IWS has none of these things (the mass protest in Poland, on the other hand, did). And that’s not to say it couldn’t. Two of the authors of the book are high-profile academics at The New School, which has no childcare, underpays its graduate students, and — I am just guessing here — does not promote or pay its female faculty at the same rate as its male faculty. Fraser and Arruzza have been quite successful at mobilizing participation in the IWS from among New School students and faculty. (Full disclosure: I am a former New School student and I am quite fond of both Fraser and Arruzza.) That is leverage at an institution that is already easily pressured. But it is not used.

Frightening symmetries

The terrible upshot to this lack of demands is that it fits hand-in-glove with the contemporary neoliberal capitalism the authors are trying to criticize.

Capitalism, the authors repeatedly warn us, is wily. For example, it has shunted a great many workers – especially women (they are right about this) – into precarious, low-wage, low-prestige, part-time, temporary, service-sector jobs, and it has described this using obfuscating terminology like “flexibility,” the “sharing economy,” and the “gig economy.” This new approach to employment is packaged as versatility for a changing workforce, but it is a calculated strategy to convince workers that they are barely necessary and that employers owe them nothing.

But look at the tactic of the women’s strike. Its flexible, nonspecific, non-withdrawal of labor contains a depressing symmetry with the above. “This isn’t the same old, boring economic strike that you’re used to” beautifully mirrors the “We don’t really employ you” of contemporary casual employment arrangements. The alleged obsoleteness of unions advanced by the authors of the Manifesto perfectly echoes the obsoleteness of unions advanced by… contemporary neoliberal capitalism. The ambiguity of the tactic of the International Women’s Strike suits capitalismjust fine.

Strikes and reproductive labor

The promise of the women’s strike, again, is that it can uniquely address the other reality of women’s exploitation under capitalism: reproductive labor.

I will say that the authors’ emphasis on reproductive labor is extremely welcome. The theory has been around since at least the 1970s and yet it is still largely ignored, even by people on the left. But it is fundamental for understanding capitalism and work. The authors rightfully point out that capitalism draws upon this kind of work while pretending it doesn’t even exist. Under neoliberalism, capitalism demands more and more from the sphere of social reproduction by paying workers less than a living wage and slashing the welfare state, and women bear the brunt.

How can this be changed? This is what interests me most of all: the website is called “organizing work” (and I am myself the mother of two small children). Can reproductive labor be organized?

The authors of the Manifesto argue that the women’s strike addresses reproductive labor too: “Withholding not only waged work, but also the unwaged work of social reproduction, [women’s strikers] have disclosed the latter’s indispensable role in society.” That’s a pretty grandiose claim for this series of protests. But even still: how exactly does the women’s strike work?

After all, there are a number of differences between productive and reproductive labor that make the strike tactic appear ill-suited to the latter. If I strike in a workplace, my intention is for my employer to lose those profits — forever. If I “strike” my reproductive labor – say, to attend the Women’s Strike — it will either create a backlog of work (dishes, shopping) for me to do later, or that work will have to be devolved onto someone else, paid or unpaid. The authors of the Manifesto note that this is exactly the dynamic involved when privileged middle-class women outsource their reproductive work to migrant women, paying nannies and maids to take care of their households and children so they themselves can go to work. And as the authors point out, this doesn’t make any progress towards changing the status of reproductive work under capitalism.

Workplace strikes deploy collective action by workers against bosses and their profits, thus shifting the power relationship in the workplace. What power relationships are shifted in the reproductive labor strike?

For that matter, who are we striking against? I recently learned that the boss of the restaurant that I have been organizing for the past three years describes that period as “the worst years of my life.” I like that; it means we’re winning. But if I strike my reproductive labor, I don’t actually want my children to suffer. One doesn’t have an oppositional relationship with the commanders of our reproductive labor, the way one does with bosses. If we aren’t striking against the objects of our care, the children and sick spouses and elderly parents who cannot stop needing that care, who is it? Our obtuse husbands? Male bosses and politicians and members of society who don’t realize just how much women do?

That is how the Icelandic women’s strike of 1975 is often presented: when 90 percent of women streamed out of work and foisted the children on their dads, workplaces were in chaos, men were overwhelmed, and the stores sold out of sausages (easy to prepare and serve). Society got such a shock that, among other things, legislation was passed guaranteeing gender pay equity the following year.

But of course, striking against individuals and their conscience doesn’t really effect structural change. In fact, that’s not what happened in Iceland either. The real story is more complicated: the one-day protest was part of a much larger campaign coordinated by labor unions, political parties, and NGOs. Sadly, today, women in Iceland are reportedly back to earning 64.15% of what men do.

The terrain of struggle for reproductive labor can only be the institutions administering society – most of all, the state. This is what we must target to make structural changes to reproductive labor, for example by demanding free universal childcare programs, or universal health care, or the buttressing of the welfare state (or, for that matter, wages for housework).

Making such demands and leveraging power in that broader terrain of public policy is admittedly less straightforward than making demands in a workplace, and, the authors are right, it certainly won’t happen by electing the likes of Hillary Clinton. But it does on occasion happen successfully; it’s how we ended up with reproductive rights and public schools and laws against sexual harassment. If, as the authors point out, those policies always leave poorer women and women of color behind, that’s a challenge to formulate better demands and the power to go after them. Protest may even go part of the way toward accomplishing the needed change (although it remains unclear to me how such protest strikes reproductive labor).

The authors of the Manifesto argue that a wholesale renovation of social institutions is needed, not to mention the overthrow of capitalism. They argue that legislative change is inadequate. But again, to withdraw from specific goals using specific leverage against specific targets is a mistake. It mirrors the way that, as the authors describe, capitalism has hollowed out democratic political institutions, devolving decision-making onto technocrats. “We’re not really in charge,” say the politicians blindly slashing social welfare to serve market imperatives. To which the International Women’s Strike responds, “We’re not really asking you for anything.”