Nick Driedger describes how the grievance process pushes unions to act more collaboratively with management and settle for less. This article is based on a talk he delivered to the Canadian Organisation of Faculty Association Staff (COFAS) at their annual conference on June 1st, 2019.

Boundaries

I’ve been asked to put together some thoughts on setting boundaries with management when you are a union representative working on grievances.

I want to start out with a story about another union. Like a lot of stories about grievances, this story begins with bargaining. The union in question had what they considered a “good” relationship with the employer. There was a give and take: while some grievances went the distance, a lot were settled early.

Bargaining was referred to as “collegial” by both parties involved. During bargaining, the union had managed to get a very strong piece of language, and they were pretty proud of the progress they had made on the issue. A year later, the employer violated the agreement and the union found themselves grieving that.

The union was caught off guard when their staff rep handling the grievance got a very angry phone call from the labor relations people with the employer. They said they felt “betrayed” and said they believed the union had pulled one over on them. After that grievance, which they settled in the union’s favor, the employer made sure they had a very aggressive labor lawyer with a union-busting reputation at the bargaining table.

Now of course, the union was just doing their job. There is really nothing to be ashamed of in striking a good bargain and if the employer did not understand what they were signing it was on them. It is also just as likely that the employer knew what they were signing.

The simple fact is that any attempt to hold the “relationship” over the grievance representative’s head is basically making their ability to settle issues into just another bargaining chip. It is actually a low-key attempt to undermine the union’s independence.

A lot of trade unionists who work with the grievance procedure will tell you that your relationship with the employer is important when you are doing the delicate work of settling disputes and carrying them to arbitration. However, in any relationship it only takes one party to decide it’s a “bad” relationship. So what do you do? If the employer can always simply hold “the relationship” over your head, how do you deal with that?

The history of the grievance procedure

Before I answer that question, I want to talk in very broad strokes about the history of the grievance procedure. You see, in the past, unions were much less legalistic and they used much more direct means of pressuring management. While it would be simplistic to say every issue was dealt with by a strike, a variety of means of disrupting management were used to pressure the employer to back down or compromise on day-to-day issues on the job, and to enforce the contract. Some unions resisted the move towards a more legalistic kind of unionism, but they were marginalized and sidelined as the CIO and AFL consolidated their power and established what unions looked like. By the post-WWII period, respectable unionism meant that contracts were negotiated, violations of the contract were handled by the grievance procedure, and ultimately arbitration settled most disputes in between contracts.

Now if you look at the Preamble to the Alberta Labour Relations code, you can see that the overriding priority is that there needs to be an orderly means of settling disputes, in the interest of remaining competitive in the international economy. So it’s pretty clearly a political document, and it isn’t remotely a socialist one.

The grievance procedure was never a popular demand from the shop floor; it was a system for sorting out problems, and triaging issues between union officers and the workers at any given enterprise.

But if every grievance went to arbitration, the costs for the union would be outrageous. (They would also be outrageous for the employer.) It would be a huge drain on the union’s resources: hearings require a lot of staff time for prep, working on the files, working with the lawyers to get the case together. It is a structural feature of the labor relations system that it is expensive, and much like divorces, the real winner in a lot of disputes is actually the lawyers. The main difference being that under capitalism, a divorce can end. Between employers and unions, you re-live that legal battle every time both parties won’t back down.

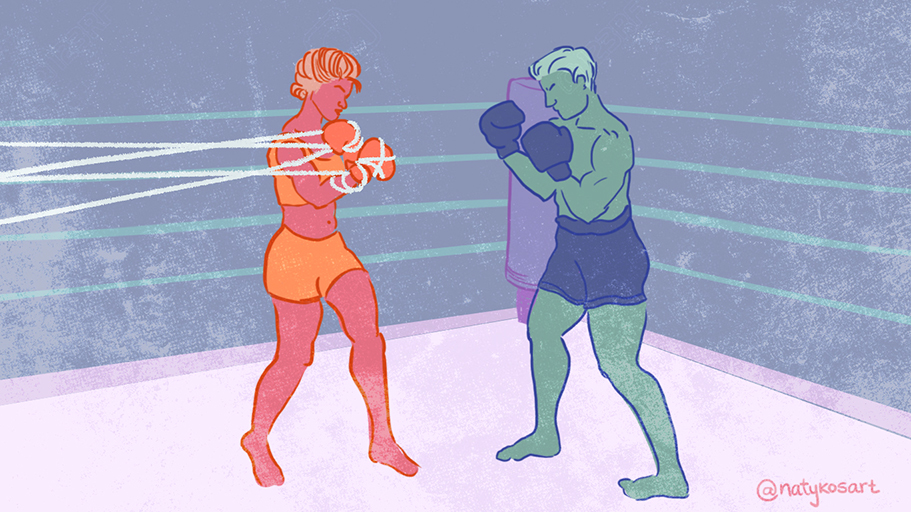

There appears to be an equal relationship under this system: bosses can’t lock their staff out just like the union can’t strike. But because employers and workers are not equal parties in our economy, any sort of equality under the law is just a sad joke. Just like the poor and the rich alike are forbidden from sleeping under bridges the boss is absolutely not allowed to conduct a wildcat strike under the law. The important thing is that unions cannot challenge management’s rights to manage the workplace, and a lot of stuff that is to the workers’ detriment is covered by that. While on paper you can’t simply shut down a business to drive out the union, you can do all sorts of things (layoffs, speedups, automation, forced overtime) motivated by “business considerations” that are really at root political.

Under capitalism, bosses and workers often see things differently, and if there isn’t a limit on how often workers disrupt production, there is a real danger that will eventually cause problems for the overall stability of the political system. The labor relations laws and the requirement for no-strike clauses are what enforce this limit under our system. This means there is a strong structural incentive for unions to find other ways to settle disputes.

Holding the relationship hostage

This brings us back to our problem: if you need a “good relationship” to settle grievances, what do you do when the employer tries to use the relationship itself to leverage demands against the union? All contract disputes are at root power struggles, and the union is the junior party, legally speaking. Not only can you not legally strike over everything, there is the practical concern that you can’t lead everyone out the door over the fact that the employer used Jimmy’s vacation time instead of sick time on the tracking system because they didn’t agree with his doctor’s note. Some issues are just more conducive to a mass campaign than others, and some issues are better handled with a bit of discretion and finesse in the interest of not making everyone’s personal life the subject of giant battles that span the whole workplace.

I want to tell another story now, this time about a pretty conservative workforce: university professors. In this workplace, there was a piece of language in the contract that said teaching staff who were on fixed-term contracts were supposed to get any permanent jobs that became available if they were already doing that same work without any issues. However, the language had gone largely unenforced for a number of years.

In academic jobs, the staff sit on a hiring committee and are often kind of led around by the human resources people and the dean. In this case, though, the staff brought forward concerns that one of the candidates for a job was basically performing the work already as a fixed-term staff member and should simply be given the job. The dean and the human resources people tried to block this, but all of the rest of the members of the committee threatened to publicly resign from the committee and tell the entire university and the broader academic community what had happened if the fixed-term staff member was not hired for the permanent job. Eventually, the dean and the human resources people backed down and the individual was hired.

Now, what does this have to do with having a relationship with the employer? It doesn’t. The relationship didn’t matter because it wasn’t a formal grievance process. All of these concerns about relationships and boundaries are concerns for those navigating the grievance process and enforcing the contract, in a system that is designed to force both parties to compromise. When you step back from that system, the “relationship” becomes a lot less important. Under these less formal circumstances, there are still opportunities to compromise and head things off when they don’t need to turn into major issues, but it then becomes a more honest calculation about who has the power needed to resolve the issues in question, and what are the best possible terms of settlement.

Disputes between the union and management are a power struggle. The legal process is designed to obscure this and make it look like you are settling a dispute like two neighbors arguing over where the property line is. But that’s inaccurate. And you should never get into a power struggle without a clear idea of where your power really comes from.

Nick Driedger is a former member, shop steward, Local Organizing Officer and National Organizing Coordinator for the Canadian Union of Postal Workers. He is currently the Executive Director of the Athabasca University Faculty Association and a member of the Industrial Workers of the World.