Eric Dirnbach and Marianne Garneau talk about the possible impact of the NLRB’s proposed rule stripping student workers of the right to organize.

Last week the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) announced it was proposing a new rule covering students. The draft NLRB rule would establish that “students who perform any services for compensation, including, but not limited to, teaching or research, at a private college or university in connection with their studies are not ‘employees’ within the meaning of Section 2(3) of the Act.” In other words, student workers would no longer have the same legal protections in forming unions, would not be allowed to file for union elections, and their employer — the university — would no longer have the same legal obligation to recognize or bargain with them. The reason is that the Board would consider students’ relationship to the university to be “primarily educational” rather than economic. The Board will collect comments for 60 days and then make a final ruling.

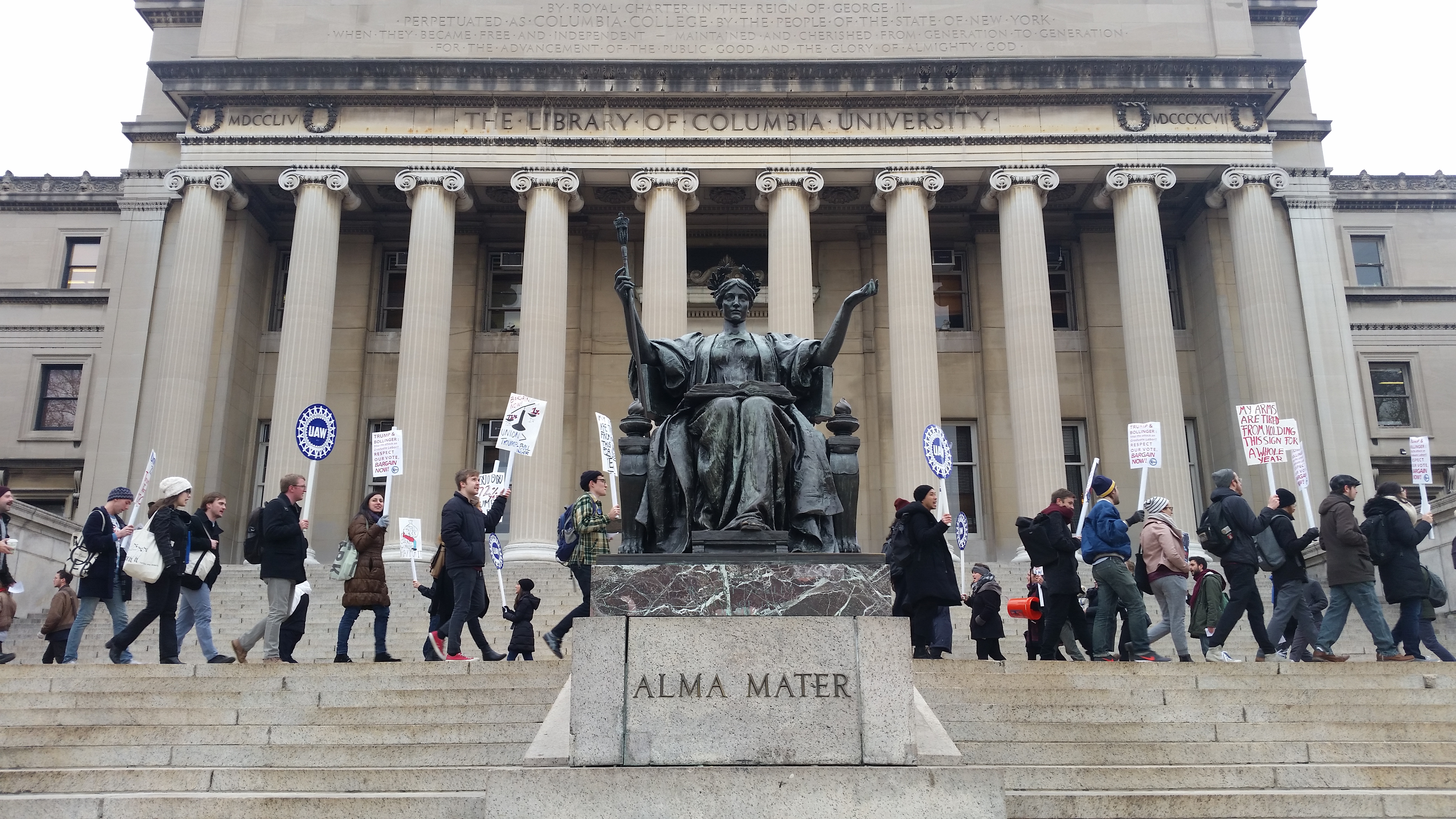

For folks following the many twists and turns of the student worker unionization movement over the past 20 years, this was an anticipated move. The NLRB has changed its mind three times on this issue, ruling in 2000 (the NYU case) that graduate students who do work for the university can be considered employees under the National Labor Relations Act. Then it reversed itself in 2004 (the Brown University case) and back again in 2016 (the Columbia University case). These changes coincided, of course, with changes in the politically-appointed leadership of the NLRB, and now Trump’s conservative Board is poised to change course again. If the Democrats win back the presidency, it wouldn’t be surprising to see another change in the future.

This decision comes during a flurry of organizing in recent years. Graduate employees have held 15 elections at private universities, voting for a union in 12 cases, and negotiating a contract at five schools —American University, Brandeis University, the New School, New York University, and Tufts University. Four schools with certified unions—Harvard University, Columbia University, Brown University, and Georgetown University—are bargaining over their first union contracts now. It’s unclear what will happen with those negotiations, but if this proposed rule goes into effect, the universities can choose to cease bargaining and withdraw recognition.

It’s also not entirely clear what the implications would be for existing contracts. Outside of NLRB jurisdiction, no “Unfair Labor Practice” complaints can be filed for violations of a contract. It is possible, however, that civil suits could be brought by either party if the other side violated the collective bargaining agreement.

Caroline, a fourth-year philosophy graduate student at NYU, who has previously worked as a unit representative for the union there (GSOC-UAW), says, “It’s not clear how it affects our position, because NYU voluntarily recognized our union in 2013. There’s no automatic effect, though it doesn’t help our position.” The current contract expires in August of next year. “The university hasn’t given any clear signs they won’t negotiate with us for our new contact,” Caroline says, “though something similar happened earlier in our history” — when the NLRB ruling in 2004 stripped students of the right to organize, NYU waited out their contract with GSOC (it expired the following year), and then stopped recognizing the union. There followed a nearly year-long strike “which [the administration] resorted to desperate, dirty measures to break,” and ten years elapsed before students bargained another contract.

Bahareh, a sociology student at The New School, and chair of the graduate student union there (SENS-UAW), says “We expect the New School to abide by the contract that we’ve got, which is valid until 2023” — it was just negotiated this past December — “And we expect them to negotiate a new contract with us when this is over.” She points out that NYU’s administration began negotiating with GSOC before the 2016 Columbia ruling again recognized student workers’ right to organize. If the new rule goes into effect, she says, the union will continue to file grievances on behalf of student workers — they’ve filed several since the contract went into effect in February, and two have already gone to arbitration. While she hopes the rule gets reversed, she also points out that “who really should be worried is the administration, because now the only way that students can show that student work is work is by going on strike.”

Other university administrations were likewise talking to unions even before the Columbia decision. Some negotiated framework or neutrality agreements, whereby the administration agrees to recognize the union should a majority of students vote for it (at Cornell, however, the framework agreement did not stop the administration from fighting the union, resulting in a narrow loss for Cornell Graduate Students United). Framework agreements are a way for both parties to hedge against uncertainty — useful when the NLRB flip-flops as much as it does. Nothing about the new rule prevents universities from recognizing student worker unions and bargaining with them; they would just no longer be legally obligated to. Ultimately, it will all come down to how much pressure students can bring to bear — this is basically the universal truth of organizing.

Are students workers?

As for the issue of whether students are workers, the controversy is most acute in the case of graduate students. It hinges on how we should understand their relationship with the university. Of course they are there as students, working on advanced degrees. But in the process, they also do research and teaching work that is real and compensated. That’s where the supposed confusion comes in. Does that compensated work make them employees or should that be considered some sort of financial aid for students?

For us the issue is settled when we consider that the work grad students do is essential for the functioning of the university and not just make-work solely to help them learn. Grad students make up between 20 and 30% of instructional faculty at research institutions.

Caroline observes that “The more they exploit our labor, the more keen they are to argue that our labor isn’t labor. But any grad student knows how much work we do for the university, and that the university absolutely couldn’t run without us. Even granting that we do get an educational experience out of this, this doesn’t have any bearing on the fact that what we do keeps the university running, and generates value for it.”

Bahareh says, “If you read the text of the ruling, the Board is so out of touch with the realities of our lives as workers at a university. For the most part, students need to work because they need to pay their bills, they need to eat. Anyone connected to universities in any capacity knows that. So this is an orchestrated attack on labor in general.”

The American Association of University Professors has noted that teaching assignments for graduate students are “often billed as ‘professional apprenticeship’ for graduate students” but many “come with little or no training for the teaching profession.”

Further, most teaching assistantships do not advance progress toward a degree; in fact, they often hinder it when graduate students’ work duties take so much time that they detract from studies. While teaching a few courses can be a valuable learning experience, many teaching assistants instead operate as a source of cheap labor for the academy, teaching section after section of introductory or developmental courses.

Source: https://www.aaup.org/sites/default/files/10112018%20Data%20Snapshot%20Tenure.pdf

This issue has been clear at the state level for decades: over 60,000 grad students have unions at dozens of public universities. A list of graduate unions from the Coalition of Graduate Employee Unions is here.

When one of the authors was in grad school at the University of Michigan in the 1990s there had been a union for about 20 years, and while the relationship with the university was often rough, it was non-controversial that graduate workers were organized and bargaining contracts. The university president at the time was Lee Bollinger, who is now at Columbia. Bollinger dealt with the union at Michigan but resisted recognizing the Columbia grad union after their 2016 union vote. In an open letter to Bollinger in 2017, one of the authors reminded him what the NLRB stated in the Columbia case:

The Board has the statutory authority to treat student assistants as statutory employees, where they perform work, at the direction of the university, for which they are compensated. Statutory coverage is permitted by virtue of an employment relationship; it is not foreclosed by the existence of some other, additional relationship that the Act does not reach.

The NLRB was right in that case and it’s actually really simple. There is a clear employment relationship, even if grad students also have an additional relationship.

Why graduate students need to organize

Organizing among graduate employees has to be understood as part of the ongoing crisis in higher education employment. Over the past decades, tenure-track faculty jobs have been growing much more slowly than the production of new PhDs. Moreover, universities have increasingly relied on graduate employees and non-tenure-track lecturers and adjuncts, who themselves are also organizing unions. A 2018 Economic Policy Institute study found that almost 75% of the academic workforce are these non-tenured-track workers:

Higher education has a firmly entrenched two-tier teaching system, with good jobs for tenured professors and precarity for the vast majority. For graduate students, their long years in school will likely no longer lead to a job as a tenured professor, which is itself an incentive to organize a union for improvements now, and to support adjunct organizing efforts as well.

Where to go from here

Even with this decision, student workers will still continue to organize, of course. And unions showed little sign of drawing down their investment in student organizing in the ten years that the NLRB didn’t consider students eligible for protections under the Act.

The danger with the new rule (and we point out that this would be the first time the NLRB has made a decision about graduate students’ rights outside of hearing a particular case) is not only that these student employees won’t be able to hold NLRB elections if they want, but that their NLRA section 7 organizing rights won’t be enforced. Thus it would be possible for grad workers to be legally fired for engaging in job actions. They may not be eligible for expulsion as students, but their ability to continue their studies may thus be undermined. In 2005, NYU threatened to take away stipends and teaching assignments from graduate students on strike.

However, in the absence of formal NLRB protections, the full range of organizing and protest tactics are still available, and they do get results. Ultimately union strength and solidarity will be the best protection against retaliation, as always.

Nor does the absence of NLRA protections strictly imply that graduate students can’t win recognition and force universities to the table. NYU students finally bargained their second contract in 2015 (after a tough, ten-year slog) — before the Columbia decision again recognized graduate students as workers. NYU students did so by pressuring the university through tactics ranging from petitions to sit-ins, culminating in a strike authorization vote.

Students at NYU have also won gains beyond the scope of the contract. Caroline relates that at Steinhardt (a division of the school), they won guaranteed funding packages. What started with a grievance — “NYU was charging fees that our contract expressly forbade them from charging,” Caroline says – broadened to a fight for further gains. “Our goal is always self-organization and empowerment at the department level.”

For that matter, student worker organizing doesn’t have to pursue formal recognition and negotiation, but may take a less traditional approach. Real gains can be made even without elections and contracts.

To give an example, in 2009, students at the New School won a 25% raise for teaching assistants, and 67% raise for teaching fellows. There was no union at the time: that raise was secured through direct pressuring of the administration. Students diligently researched graduate pay rates across the country, put together their case, and presented it to the administration at meetings and town halls. The administration dragged its feet until a group of students (motivated by this and other concerns) occupied a building on campus, drawing significant public attention and skirmishing with police. The administration quickly conceded on the raises.

Compare that situation to roughly ten years later when graduate students won formal recognition through the UAW. Many were hoping for a 70% raise — their pay had been stagnant since 2009. Ultimately, the contract (like many modest first contracts) secured 2% per year.

An example of sustained organizing outside of the contract model is to be found in the CWA’s United Campus Workers, which has a presence across several campuses in the southeast. In most of those states, the law impedes rather than facilitates bargaining, through “right-to-work” laws or a ban on public sector bargaining. Jacob, a graduate student in anthropology at the University of Georgia who sits on the UCW’s steering committee, notes how these legal restrictions can be turned into an advantage: rather than worrying about carefully-carved bargaining units, “we can organize wall-to-wall — that includes clerical and maintenance staff, graduate student workers, faculty, and so on.” Indeed, students and faculty have won concessions for custodial staff. Kate, a researcher with UCW, notes that “We have no legal permission but all the worker power we need.”

UCW fought the University of Georgia about graduate student health insurance, with some success — they got a proposed increase to premiums cut in half, and the Board of Regents committed to designating a staff person to represent graduate students’ interests to the health insurance company. They are now working on a campaign to reduce institutional fees, which can run upwards of $1,000 per semester, on top of tuition costs.

There is a security to formal contracts, but it’s also possible for a campaign to stagnate when it becomes fixated on that goal. A recent article in n+1 magazine gave some insight into the 47-year campaign at Yale to obtain recognition from the university, as yet unsuccessful.

Finally, it’s worth noting that the withdrawal of NLRB jurisdiction cuts both ways. Robin J. Cartwright, a former adjunct professor with a PhD in labor history, notes that “it’s no longer an ‘Unfair Labor Practice’ for the union to violate a no-strike pledge, or engage in secondary strikes or boycotts.” Absent NLRA coverage, “The union and management have broad freedom to make up their own rules.”

Labor law is a political compromise that tames unions in exchange for employer concessions. If the NLRB wishes to remove that political compromise, graduate student workers should heed the signal that all tactics are back on the table. Indeed an NLRB board member’s dissenting opinion on the proposed rule anticipates a rougher era of labor relations, stating “today’s proposal will raise the specter of renewed unrest on campus. That result is directly contrary to the Act’s stabilizing purposes.”

Comments for the new proposed rule can be submitted here.

Eric Dirnbach is a labor movement researcher and activist in New York City. Marianne Garneau is an organizer with the IWW and the publisher of Organizing Work.