Marianne Garneau traces how the IWW carved out a unique training program and novel approach to organizing.

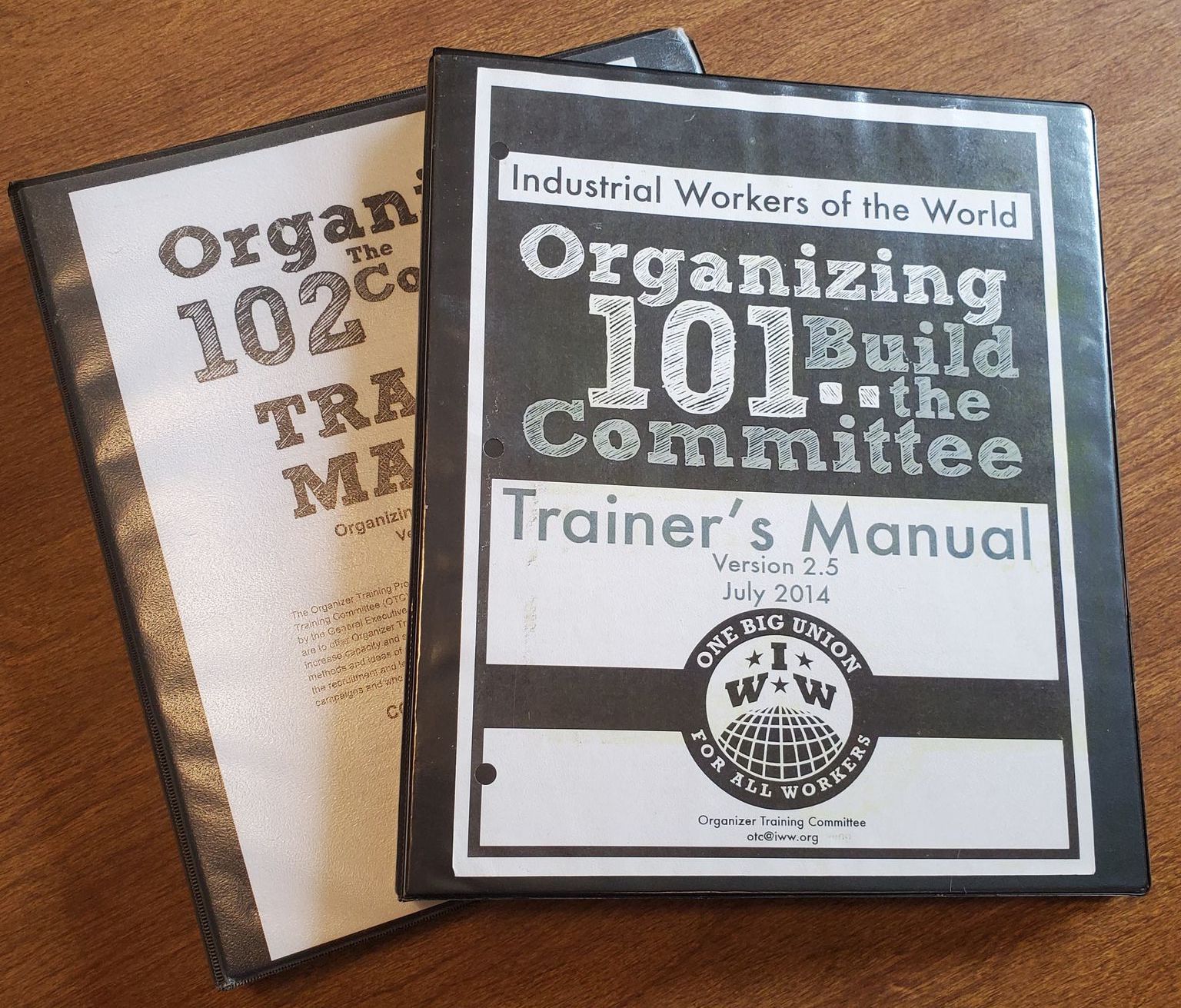

The IWW has a rather unique organizer training program among labor unions. It involves two intensive, two-day workshops, open to any member or worker, building the skills they need to organize their workplace, from gathering contact information for their coworkers, to having one-on-one conversations with them, to building an organizing committee, to collectively handling grievances. The first training, “Organizer Training 101: Building the Committee” is meant to take any given participant from zero prior organizing experience or knowledge, to undertaking their own campaign at work and even mounting a modest direct action with coworkers to settle a grievance or win a demand. The second training, “Organizer Training 102: The Committee in Action” presents a systematic grievance handling process based in workplace action, as well as the nuts and bolts and strategic questions involved in maintaining a functioning shop committee.

The curriculum is geared not towards staff organizers but towards workers, teaching them how to organize their workplace themselves, without the intermediary of paid union staff. The ultimate objective of the IWW approach is to build a horizontal, majoritarian effort of workers, led by a representative shop committee from among their own ranks, capable of organizing direct action in the workplace to address issues and secure new gains. The approach is an alternative to the steward system and the standard bargaining, grievance and arbitration processes, which take place away from the shop floor and rely on lawyers or other professionals. The IWW’s position is that, besides being expensive and slow-moving, these processes are meant to forestall shop-level action, especially economically disruptive action — “work now, grieve later,” as the saying goes.

All of this makes the IWW’s training exceptionally democratic among union training programs. It is also democratic in its structure, built around a “train the trainer” approach. Any member can take the courses, and any participant can then apply to attend a certification and become a trainer themselves. The program, which is overseen by an elected committee of five trainers, is remarkably stable and sustainable for being completely volunteer-run, on a limited budget (trainers are compensated for travel and given a small per diem). It has grown in capacity — number of trainers, frequency of trainings — consistently since its inception almost 20 years ago, and has probably trained thousands of individuals in that time. It is one of the most popular and beloved aspects of the IWW for members and the cornerstone of the union’s most effective organizing campaigns.

The development of the IWW’s organizer training is an interesting story, for it tracks the union’s formulation of its own unique approach to organizing over the last few decades. For a long time, especially after the loss of the Cleveland machine shops in the 1950s, the union floundered with almost no workplace presence and a voluntary activist membership (anyone other than a boss can take out a “red card”) numbering only in the hundreds. Every time the IWW tried to re-invest in worker organizing, it borrowed from mainstream union approaches, with mostly disappointing results. The impetus for the training program was yet another “let’s get serious” moment in the late 1990s and early 2000s, with campaigns springing up around the union; the training was an attempt to deliver best practices to do-it-yourself, boom-and-bust campaigns.

At first, the IWW again borrowed materials and techniques from mainstream unions, courtesy of members who were “dual-carders,” working as organizers or stewards elsewhere, or having been trained by other unions, including at the AFL-CIO’s “Organizing Institute.” What began with fairly widespread techniques and strategies, with an added political critique of labor law, evolved into a genuinely different approach to building worker power, as the shop committee system was carved out.

The current “fight for gains, not for recognition” approach makes the IWW an outlier in the labor field, as it always has been, but finally brings the union back to its revolutionary roots rejecting comprehensive contracts and labor-management cooperation. “The Industrial Workers of the World do not recognize that the bosses have any rights at all,” testified Big Bill Haywood before Congress’s Commission on Industrial Relations in 1915. “We say that no union has a right to enter into an agreement with the employers … because it is the inherent mission of the working class to overthrow capitalism and establish itself in its place.” Throughout its long period of dormancy – while comprehensive contracts including no-strike clauses and management rights clauses became the norm – the IWW maintained the position that labor relations law was no gift to the working class. But this was somewhat academic as the union had no distinct organizing approach and few shops.

Although in recent decades, other unions have grown more cynical about the National Labor Relations Board and the courts, the IWW is unique in presenting a model for workplace bargaining outside of recognition elections and contracts, without relying on foundation-funded advocacy or election-driven coalition-building either – just shop-floor worker power.

What follows is a nearly five-decade history of the IWW carving out its organizer training and its approach to organizing in general. I begin with some manuals on organizing made available to the membership in the 1970s, and end with the latest developments in the current program. The research is based on a review of every training manual the union has produced since the 1970s, as well as archival materials such as the Industrial Worker newspaper and General Organization Bulletin, and a dozen in-depth interviews with current and former members.

Prehistory of the current program: Organizing pamphlets and manuals from the 1970s through the 1990s

A Worker’s Guide to Direct Action (1974)

Prior to the development of the in-person training program helmed by the Organizer Training Committee, members had access to a number of pamphlets and manuals about organizing, put together by members and available through General Headquarters or branches.

One was “A Workers’ Guide to Direct Action,” a 15-page pamphlet which gave short descriptions of such tactics as slowdowns, work to rule, sitdowns, sick-ins, and whistleblowing. The pamphlet was actually an abridged rewrite of one put out by Solidarity in the UK in 1971. The IWW’s version presents these tactics as an alternative to two things: the “clumsy and slow” step-grievance procedure “whereby a dispute goes through a series of conferences and ends up being decided by ‘arbitrator’: usually a lawyer or professor.” And the “long strikes” which “cost too much and are too exhausting to be used often.” Besides, it notes, “the AFL-CIO-CLC officials… hoard up big strike funds.”

The pamphlet was reformatted and very modestly updated over the years, for example by the Lehigh Valley branch in the 1990s, which rewrote the introduction, now describing the historical origins of the legal labor relations framework as trying to contain the class war, and framing direct action as “guerrilla warfare.” It was also republished by the Edmonton branch in the 2000s as “How to Fire Your Boss.”

While the use of shop-level job action is consistent with the IWW’s historical approach, the writing is addressed to the individual worker and contains no advice for agitating or developing coworkers, nor about campaign-building, nor about handling retaliation for deploying these direct action tactics. It notes that to use these tactics, you need “job organization,” at least in the sense of a “general agreement that conditions on the job need changing,” but the colorful examples taken out of context are somewhat aspirational if not irresponsible.

Organizing manual (1978)

Another series of pamphlets – this time written by IWW members — was produced in the 1970s. These included an Organizing Manual and a Bargaining Manual. “The problem of how to grow – how to reach out and organize – dominated the [1971] Convention,” according to the memoirs of one Ottilie Markholt, a long-time labor activist from the Pacific Northwest but at the time a new wobbly; a “deceptively grandmotherly looking woman who was in fact a hard-nosed unionist” according to a posthumous tribute in the Industrial Worker some thirty years later. Markholt says, in light of this new priority, “A group of delegates met informally to plan an IWW organizing manual… The convention approved our plan and named me coordinator.” They “mulled over the problem of Wobblies as organizers, with an ever widening circle of correspondents,” including IWW luminary Fred Thompson. They eventually produced a 23-page manual for sale at GHQ.

On a practical level, the manual echoed good, standard organizing advice of the time: it instructed the reader to get a list of workers – although with little technical advice – and do house visits. It emphasized the importance of face-to-face connection, but also described hosting large meetings for the purpose of talking to workers about the union (using mass meetings for outreach has been abandoned in the current training program: it is too vulnerable to leaks, and caters to the lowest common denominator). It soberly advised building a committee that was representative of the whole workplace – including “each department and/or shift” and “each ethnic and racial group… balanced for age and sex according to workplace ratios.” It insisted that the union “must be a majority movement, or it will be nothing” and talked about the importance of developing “democratic working rules.”

The manual tracks mainstream union approaches all the way to campaigning for an NLRB win. Most of its advice centers around winning an election or formal recognition through other means like picketing or striking (trainers today would counter that formal recognition through these other means no less sets one upon the path of formalized labor relations). The section on union-busting is focused on legal employer stall tactics around an election. A sample authorization card is included.

Fascinatingly, this focus on elections comes despite a warning that:

contrary to official Liberal-Labor myth, the right to organize and bargain collectively was not written … out of love for Labor. Rather, that legislation was passed to contain Labor’s growing rebellion… Therefore, while you may encounter sympathetic examiners and attorneys in regional NLRB offices, you are essentially being governed here by a hostile body of law.

In fact, a lengthy section towards the beginning of the manual laments the IWW’s recent capitulation to the labor relations framework, arguing that in doing so the union has lost track of its foundational insight that worker power is based in worker action, and not government intercession (emphasis added):

In recent campaigns, we have ignored the basic difference between the IWW and every other union: recognition of the class struggle, and the fact that the only way to end that struggle is by abolishing the wage system. We have come on as a bargain union with cheap dues and low or unpaid officers. We have blamed bureaucratic and/or corrupt officials for the failures of other unions.

The authors are clear that other unions are not corrupt because of their officers’ moral failures of character, but because they are ensnared in a governmental framework that ties workers’ hands (emphasis added again):

The conventional unions are based on the premise that Labor and Capital are partners, with the Government as umpire, in a system of class collaboration that will benefit both parties… in recognizing the government’s right to umpire the partnership, those unions renounce their one real source of strength, economic power…

The local officials reflect those contradictions. They may be very honest and sincere people, but they are immobilized by those contradictions. Even if they, themselves, understand the class struggle and would really like to see their locals bargain on that basis, they simply can’t accomplish much against the weight of the rest of the union.

Again, the authors point out the folly of thinking that the IWW can participate in the labor relations system without falling into the same traps as other unions. And they point out how participating in that legal framework constitutes an abandonment of the idea the IWW was founded on:

We have tried to chop the IWW in two and separate the Preamble [which states that the working class and the employing class have nothing in common, and that the wage system must be abolished – MG] from the union as a vehicle for winning immediate demands. The thrust of our campaigns has been, in effect: forget about these visionary ideas. We believe in them, but we don’t expect you common working people to. Just take us as a pure and simple union for the present. We have tried to sell ourselves as a good, young, poor, clean union versus a bad, old, rich, corrupt union. These campaigns have been uniformly unsuccessful.

In other words, worker action at the point of production is essential to building working class power and winning demands, and yet this is what the NLRB system has worked so hard to whittle away. The IWW, entering into that system, can do no better.

With this Organizing Manual, we are left with the contradiction of a clear-eyed analysis recognizing these constraints, which yet could only advise IWW members to pursue the same legalistic strategies as other unions. While the IWW had set itself the goal of wresting itself from historical irrelevance and once again organizing workplaces, it did not yet have a model to pursue this. In this early manual, strategy did not match goal — or practice, theory. There was no way of institutionalizing the commitment to worker-driven or class-struggle-based organizing. The IWW did not yet have its own organizing program.

Collective Bargaining manual (1978)

The Organizing Manual was released alongside a 33-page Collective Bargaining manual, also spearheaded by Markholt and seemingly all the more authored by her hand.

It too reflects on worker power in the introductory sections. It frames bargaining as fundamentally a fight over control of the workplace and working conditions. But the advice that follows is orthodox material about the technicalities of defining the bargaining unit, and the three categories of security clauses, working conditions, and compensation. It does acknowledge that the IWW Constitution forbids dues check-off, since “the increased efficiency does not offset the loss of personal contact between members and the union.”

All told, the Bargaining Manual is somewhat pie-in-the-sky, or disconnected from the realities of worker power that would have to be leveraged to see its prescriptions through. For example, it contains a note about how “shorter hours at no reduction in pay should be a long-term objective for all union people” and suggests “as a start, try for a 30-hour week of five 6-hour days” – without much thought to how you would develop the kind of bargaining power to make your shop an outlier in an industry, and for that matter the whole economy.

Updates to these manuals

Both of these manuals were updated over the years, albeit not really in relation to any kind of campaign successes or losses. The bargaining manual was updated in 1983 by Paul Poulos and Rochelle Semel, two long-term members in upstate New York, who were likewise eager for the IWW to get “serious” and begin organizing workplaces and bargaining contracts. This was, again, a time when the union was mostly a home for radicals – labor-oriented anarchists and communists; union officers with a class-struggle outlook; old-timers who recalled the union’s heyday; hangers-on and fellow-travelers. The union’s total membership was still in the low hundreds.

Poulos and Semel removed Markholt’s framing introduction about workers’ power struggle with the boss. They added yet more technical sections (e.g. on probationary periods) with sample, template language for each section of a contract.

It’s unclear either the Bargaining manual or Organizing Manual were ever used, however. The IWW did achieve recognition and bargain a handful contracts in the 1980s: University Cellar Bookstore, the People’s Wherehouse (a grocery warehouse), and Leopold Bloom’s restaurant in Ann Arbor; Eastown Printing in Grand Rapids; SANE and Oregon Fair Share in Portland; and recycling plants in the Bay Area. Other than the People’s Wherehouse (which lasted ten years) and the recycling plants (which have IWW contracts to this day), the campaigns were mostly short-lived, often ending when the business closed. Many more attempts at recognition – often with a strike – simply failed.

Updates of the Organizing Manual were produced in 1988 and 1994 or 1996 (the record is unclear), incorporating feedback from across the union. The latter version backed off from the model of organizing a majority and filing for an election, noting that “a great deal can still be accomplished by a small group on the shop floor working to mobilize their fellow workers around particular grievances and to coordinate direct action campaigns…” Where the first version acknowledged the various legal tactics bosses could use to subvert or defeat a union election, the updates took a harder line, noting that

even when you ‘win’ through the labor laws, you end up losing — endless hours are eaten up pursuing the case, momentum is lost, and power is shifted from the workplace to the bosses’ courts. While you should know the law in order to make informed decisions about your options, the workplace remains your real source of strength.

It acknowledges that with the ULP process sometimes a “sweeping ‘victory’ [is] five or seven years down the road. By that time the union has almost certainly been busted and most union supporters have moved on to another job.” This was most likely a reflection on the IWW’s experience at Mid-America in Virden, Illinois, where in 1977 the IWW signed up six of seven workers, and petitioned for an election:

the long march through the courts allowed union membership in the shop to dwindle down to one by June 1978… Two years later, in the fall of 1980, with all appeals exhausted, Mid-America finally agreed to recognize the union and begin negotiations. By this time, of course, there were no union supporters in the shop… The Industrial Organizing Committee … [sent] letters to current Mid-America employees to brief them on the organizing campaign and to find out if they wished the IWW to bargain on their behalf. There was no response and the Virden campaign became history.

This experience would be repeated almost verbatim decades later, when the IWW won an election at Mobile Rail Systems in Chicago in 2013, only to lose all presence in the (relatively small) shop while it failed to negotiate a collective agreement, before finally disclaiming interest in 2020.

However, even as this version of the organizing manual was more critical of the labor relations framework, and even as it acknowledged that “It is possible — even legal — to fight for specific demands, or even to demand union recognition, without going through the NLRB,” still, most of its advice was geared towards formal recognition in anticipation of bargaining a contract.

The inception of the current training program

It is worth noting again that these manuals did not seem to get a ton of use. 1996, the year the Organizing Manual was seemingly last updated, also saw a number of high-profile IWW campaigns, and yet members of those campaigns this author interviewed did not report using it, although some were aware of it. Wobblies around the union fumbled their way through their heady campaigns, with the guidance of whoever happened to be around, with mixed success.

Also in 1996, the IWW narrowly lost an NLRB election at Borders Books in Philadelphia. A core organizer was fired, and a high-profile, national campaign was launched to boycott and protest the chain, with heavy participation from over a dozen IWW branches. In the wake of this, there followed a spate of new organizing – at the MiniMart convenience store in Seattle, Applebee’s in New Orleans, Wherehouse Entertainment in the Bay Area, Snyder’s Pretzels in Pennsylvania, Sin Fronteras bookshop in Olympia, and a string of workplaces in Portland.

Alexis Buss, a member from Philadelphia who later became General Secretary-Treasurer, says “After Borders we were getting nibbles, and people didn’t have any other way to engage. ‘What makes a union’ was still cast in this ‘how many contracts do you have?’ mold.”

She was often personally sent to assist these campaigns. John B, who would go on to serve on the Organizer Training Committee, describes the situation this way:

We had a number of national, very public, visible campaigns that totally imploded… it was basically that situation [of] a hot shop with three guys who stood up on the table and said “Workers of the world, unite!” and all the leaders got fired, etc. Alexis was just looking at these campaigns, and basically put together a one-day best practices for organizing.

Buss acknowledges, “we did try to take some time to kind of learn and do better after each failure.” She began running one-day workshops for campaigns and branches:

Say you have a [name redacted] from Applebee’s contacting your branch, what do you do with them? You don’t hand them authorization cards and make flyers for them about how bad their boss is, and say “good luck, kid.” So it was really about trying to build a committee on the job. …It tried to show the deficits of outside organizers doing the organizing work, what would happen if there was no committee, what would happen if you ignored shopfloor leaders…

Soon, a group of four IWW members began gathering materials in earnest, from mainstream unions. They included Buss, John Hollingsworth in Ottawa, a table officer of then-OPEIU Local 225 and research staffer at the Canadian Association of University Teachers, Josh Freeze, a member of the Amalgamated Transit Union and later shop steward with the Association of Flight Attendants, and Chuck Hendricks in Baltimore (later Connecticut), who became an organizer with UNITE HERE. Hendricks recalls that they “started pulling together training material from the AFL-CIO, UNITE HERE, and some other unions to try to create an organizing manual” and “classroom-style trainings.”

Hendricks was among a number of wobblies who had attended the AFL-CIO’s Organizing Institute. The three-day workshop drilled the skill of doing a “house visit,” most notably by using roleplays, at the end of which successful participants would be recruited to unions. This classroom model with roleplays became the basic structure of the OT 101.

Thus, the IWW took the original core of its initial training program from the other unions: gathering contacts, socially and physically mapping the workplace, identifying leaders, having one-on-one conversations with coworkers following the AEIOU script of Agitate, Educate, Inoculate, Organize, and Union. To this was added an analysis of how the IWW differed from other unions (no paid staff, no political party affiliations, no dues check-off), and a critique of labor law, including a cautionary “Timeline of a ULP” written by Buss, meant to warn participants of how slow-moving and ineffective legal processes could be.

The first Organizer Training 101 was held in Portland in August of 2002. Per the Organizer Training Committee’s (OTC) report to Convention,

Forty members came from all over the western United States for a weekend of formal discussions, lectures and role-plays. We covered topics from developing contacts, activists and leaders to mapping the workplace; from pushing people to take on commitments and responsibilities to negotiations; from the challenges of high turnover shops to US labor law… Without a doubt, the most frequent comment we got in the evaluations was th[at] there should be more role-plays. The trainers agree and for most trainings in the future, they will be significantly expanded.

In the ensuing years, other IWW members, again often with mainstream union experience, built out more modules: two organizers in Minneapolis who both had experience with AFSCME wrote a captive audience meeting, and a “One Big Organizer” exercise where trainees take turns asking questions of a potential union member, to Agitate and Educate them. Overall, the development of the IWW’s organizer training has been a transformation from lecture format to a popular education model.

In this way, from roughly 1996 to 2003, the training program was solidified, from informal workshops put on by Buss, to a formal program run by the Organizer Training Committee, which wrote and maintained a trainer’s manual, coordinated trainings, and credentialed new trainers. By the time the committee structure was up and running, a stable resource had been created that did not depend on Buss’s talents, who had by then moved on to other projects.

Having borrowed heavily from mainstream unions, however, the early organizer training program still bore the marks of mainstream approaches. MK Lees, who would go on to become a trainer and serve on the Organizer Training Committee, recalls taking an early OT 101 in Chicago in 2002, while he was organizing bike messengers with the IWW’s Chicago Couriers Union. “The training was still moving towards solidarity unionism… It was heavily critical of NLRB organizing, but it still had its foot in both worlds. It provided that it could be used for NLRB organizing or not” – such as among bike messengers classified as independent contractors and not employees – “but so many of the examples were from NLRB-style efforts.” While the workshop did not train or encourage participants to file for an NLRB election, the arc of the two-day training culminated in going public, like recognition campaigns do. It also presented the “stages of a campaign” as culminating in a “recognition strategy” and then “bargaining” – the IWW was basically spinning a mainstream approach that skirted the NLRB.

In other words, the union was still carving out its own approach to organizing.

Campaign applications, and revisions to the program

From 2003 onwards, the organizer training program evolved in light of IWW campaign experience.

Although the OT 101 never advised filing for an NLRB election, and instead warned participants about labor law, that lesson was underscored by the certification-oriented organizing in Portland in the late 1990s / early 2000s. In 2003, Portland released a document titled “Learning From Our Mistakes,” reflecting on four different campaigns, at a bike messenger company, two separate grocery stores, and a social-services nonprofit. The conclusions are unequivocal: “NLRB slowed down organizing”; “Bureaucracy of NLRB slowed down process, took away momentum and required a lot of time from multiple people”; “Did not have a vision of the campaign that did not include NLRB recognition”; “Did not recognize that direct unionism was working well without NLRB recognition”; “Organizing focus shifted to NLRB election rather than remaining on worker issues and the fight for real gains”; “Things to avoid doing again: Going to NLRB election”; “Using the NLRB”; “Seeking official recognition of the union”; “Aiming to win an official collective bargaining agreement”; “Abandoning democracy building amongst organizing committees to focus on the immediacy of an NLRB election”. At a campaign where the election was won: “Real issues not addressed in bargaining”; “Union was more real on paper.” “Things to do differently next time: more direct unionism tactics.” “Experiment with more minority / direct unionism tactics.”

Nevertheless, both the Starbucks Workers Union that launched in New York in 2004 and the Jimmy John’s Workers Union that launched in Minneapolis in 2010 initially sought formal recognition by filing for an NLRB election. The former abandoned this effort when the bargaining unit was deemed to include every store in Manhattan. The latter narrowly lost an election, only to have that result overturned at the NLRB, but never subsequently filed again.

As these multi-shop campaigns progressed, however – and expanded to other cities – they honed their ability to exercise direct action tactics in and around the business to win gains, including floor mats, tip jars, temperature controls, scheduling changes, bathroom breaks, raises, paid time off, and an end to management bullying, as well as turning around some firings.

With campaigns enjoying more success from direct action than from legal approaches, more training curriculum developed around that. What began as supplementary workshops sometimes given in conjunction with a 101 became a standalone 102 training, “The Committee in Action,” in August of 2010. Nick Driedger, a former member of the Organizer Training Committee and veteran of the IWW’s dual-card organizing at Canada Post (see below), notes that the program was created after a number of IWW organizing efforts took hold:

The 102 was created after we had as many as a dozen shop committees running in different workplaces and so we started to develop a system for taking in issues, targeting the right level of management and seeing the demands through in a concerted way (the direct action grievance procedure). The emphasis of the 102 was on making these committees that could last over the long haul; some of our committees existed for about six or so years.

The training involved a couple of components. One was the “march on the boss” tactic, where multiple employees confront a boss about a particular policy or staff treatment. Early long-form notes on the exercise were rewritten as roleplays that assigned roles (signal-giver, demand-deliverer, interrupter, etc.), with the trainers playing the boss.

Another component of the 102 was a section called “Parts of a Direct Action,” which analyzed the latter into ten parts, from “demand” to “participants,” “witnesses,” “target,” “tactic,” “results,” among others, and emphasized the importance of escalating pressure. In addition, remarks were made about the difference between “workplace contractualism” and the IWW’s approach, now called “solidarity unionism.” It reflected on how mediators make decisions they don’t have to live under, how contracts make most strikes illegal and push many shop floor problems off until the next round of bargaining, how they “Disempower workers during the life of the contract, usually through no-strike, management rights clauses, and recognizing the legitimacy of bosses in spirit, practice, and law.” In contrast to this, the training presented the model of a “shop committee.” It also addressed integrating new hires, effective picketing, dealing with retaliation like firings, and holding good meetings.

As campaigns continued to spring up and the training program grew in popularity, the direct action components were moved into the 101 training, which was offered far more frequently than the 102. For its part, the 102 program evolved to become a systematic approach to committee maintenance and a full-blown direct-action grievance handling process. The grievance process was developed after the successful dual-card campaign at Canada Post in the early 2010s. IWW members within the Canadian Union of Postal Workers created and ran a training program called “Taking Back the Workfloor.” They would identify social leaders on the floor and put them through the training course, using CUPW’s own education infrastructure. Driedger again:

We put about 160 people through those trainings and then added them to a text message list …that coordinated between the shop committees… We had some really big wins including: forcing Canada Post to hire 200 people when they were trying to cut jobs, through march-on the-boss actions spanning about 2,000 workers, [and] beating back a 30% pay cut for rural carriers through a four-day wildcat. Countless march-on-the-boss actions involving anywhere from 8-120 workers won demands from turning around discipline to enforcing seniority on picking delivery roots, to stopping forced overtime (which we ended for about 1,000 workers for about six years when it was going on across the post office for decades prior to that).

The 102 training’s grievance process now included a grievance sorting and prioritizing activity, and an exercise in telling workers that their own grievance can’t be pursued at this time. It also addressed issues of democratic accountability that arise in campaigns that are horizontally worker-led.

Latest developments

The latest revision to the 101 curriculum happened in 2018-2019. This was again prompted by experience: reflections on the success of the IWW campaign at Ellen’s Stardust Diner, and on the challenges faced by other IWW campaigns.

At Ellen’s, workers went public with their union in August of 2016. The employer retaliated with a staggering 31 illegal terminations over the following five months (16 in one day). The union eventually prevailed in reversing the terminations and securing back pay, in an NLRB-supervised settlement, but the campaign survived – and the settlement was forced – because of the ongoing organizing, including signing up and training replacement workers and continuing to wage direct action campaigns in the shop, in addition to pickets and pressure campaigns on the reinstatement issue. Meanwhile, the union racked up an impressive list of wins, including a new stage, safety fixes, a lactation room, increased staffing, capital improvements, raises for cooks, dishwashers and hosts, and an end to unpaid rehearsals and tip theft, all without formal recognition and bargaining. This was facilitated by faithfully following the directions in the existing 101 training, and by building out formal structure — union membership and dues payment, elected officer positions, meetings and motions, a budget – providing a counterexample to the trend of non-NLRB campaigns being loosely organized affairs orbiting around strong personalities.

In light of this experience, the 101 was revised to remove the original “Timeline of a Campaign” that culminated in “going public.” MK Lees and this author wrote two articles trying to capture the lessons at Stardust. One was “Do Solidarity Unions Need to ‘Go Public’?” noting that the move was a vestigial remainder of a certification drive where employers are formally notified of the union effort, and that, unequivocally in IWW experience, it had resulted only in retaliation and losses, whereas ongoing issue-based fights experienced no such decisive blowback.

The other article, “Boom without Bust: Solidarity Unionism for the Long Term,” was a reflection on how the IWW could maintain its model of non-contractual, solidarity unionism organizing over the long haul, now that it had a few models for doing so. (It must be acknowledged that the IWW Jimmy John’s and Starbucks campaigns lasted around a decade themselves, but had very loose structure and over time came to rely more and more on “air war” publicity, and less on presence in the shop.) The piece described the stabilizing organizational features of Stardust’s solidarity union. The training program, for its part, renewed its emphasis on signing workers up as full, dues-paying members, and adopting a systematic approach overall.

The section in the 101 training on labor law, which had grown to be an incisive but rather lengthy lecture on the political and historical context of the Wagner Act and Taft-Hartley, was now reduced to the inoculation about ULPs, and a general caution about legal processes. The nearly two-hour section had always been very divisive: either most loved or most hated among participants in their evaluations, but the trainers doing revisions realized its length was effectively contradicting its message to set labor law aside and focus on direct action.

The end of the 101 training now culminates in a note about “sustainable committees” and “next steps,” giving guidance on how workers can “level up” their campaigns without pulling the trigger on an election or going public as the payoff for their organizing, whether envisioned as a triumphant moment or pursued as a desperate move to solve flagging energy. The suggestions instead include: “expand membership” and “take on bigger demands.”

Conclusion

The IWW’s current training program now matches the union’s political rejection of class compromise and its cynicism about labor relations law. However, it was not built out ideologically or “a priori;” instead it gradually condensed roughly 25 years of experience in actual campaigns.

While its original materials were borrowed from mainstream unions, it now differs from them in every detail. The IWW’s version of AEIOU, for example, is geared towards direct action and not signing an authorization card. It is about developing broad skill sets and class consciousness among all workers. The assessment scale reflects whether a worker is actively helping the campaign through one-on-ones or direct action or administrative work, or is merely verbally supportive (at the other end of the spectrum: whether they are passively or actively opposed to the union effort).

The approach also reflects the IWW’s own structure: very low dues rates which generally do not support paid staff; committees and boards filled by member-volunteers; and campaigns in low-wage, small-shop, high-turnover industries such as retail, fast food, restaurants, and call centers, where the union’s membership tends to work, and where other unions tend not to try to certify bargaining units for obvious cost-benefit reasons.

Still, not all campaigns in the IWW follow the solidarity unionism approach (and this article has only canvassed a fraction of the drives in the last five decades). There continue to be election and contract campaigns within the union, among other models of organizing, made possible by the fact that the IWW is very decentralized. A string of elections and recognition campaigns in the 2010s – 18 of 20 were formally successful – saw many of those shops close or union presence dwindle to zero within a few years. The Burgerville Workers Union (BVWU) in Portland, which has been a contract campaign from the onset and is currently entering its third year of bargaining, is now petitioning to the rest of the union that it should be allowed to sign a no-strike clause, presently forbidden by the IWW’s Constitution, and has already committed to a (loser-pays!) grievance arbitration system. It reflects the contradictions, the early organizing manual would say, of trying to build worker power within the legal labor relations framework. The experience of IWW campaigns, in other words, even of those that don’t hem to the model laid out in the current Organizer Training, continue to reflect the lessons and warnings distilled in that program, if only negatively. But the union as a whole, through its solidarity union approach, has grown beyond a “bargain union” differentiated only by its “cheap dues and lack of paid officers,” now finally able once again to put its revolutionary ideals to practice.

Marianne Garneau is the Chair of the IWW’s Education Department Board and the publisher of Organizing Work.