Dave Powell breaks down the history of organizing in professional wrestling, and why these workers need a union.

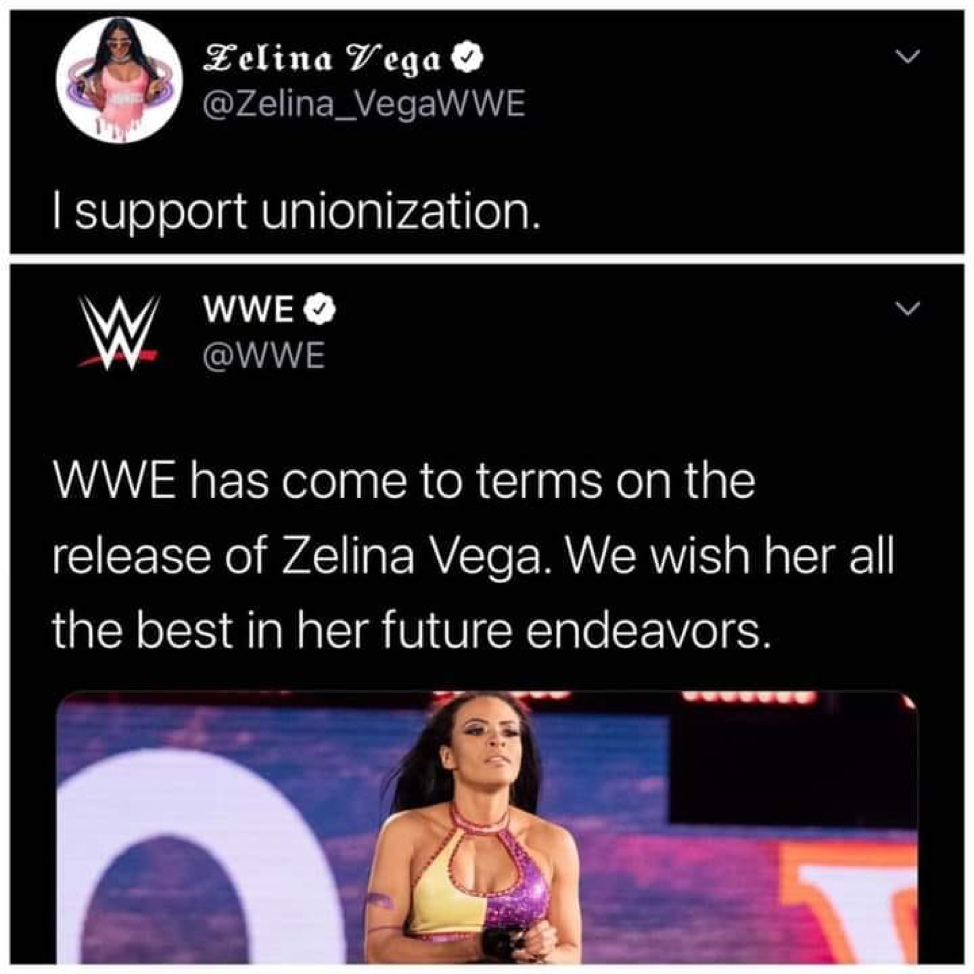

Recently a tweet from WWE professional wrestler Zelina Vega went viral, wherein she supported unionization. She was fired by WWE around ten minutes later. The actual cause of her termination is more complicated, but her tweet kickstarted widespread conversations about unionizing professional wrestlers.

Many wrestlers themselves have long supported unionizing, with famous names such as Bret Hart, Roddy Piper, Jesse Ventura, Sgt. Slaughter, Chris Jericho, Sting, Terry Funk, and Goldberg publicly speaking up about the idea. The first major documented push was in the 1970s and 1980s, led by Georgia wrestler Jim Wilson, who tried to get the sport regulated in Georgia and wrestlers placed in a union. The attempts went nowhere and led to him being blackballed by the National Wrestling Alliance (NWA), the umbrella organization governing most wrestling promotions which worked on a regional territory system (each wrestling promotion claimed a part of the US or Canada, and would tour shows; years of turf wars resulted in a code to respect each other’s territory, which the WWE broke). Jim Wilson’s efforts went nowhere, though he continued the efforts for the rest of his life with little success.

There was another push for unionization just as the WWE (then WWF) began to emerge as the first national, rather than territorial wrestling company. In 1985 Sgt. Slaughter was allegedly fired for attempting to form a union. The most famous drive was in the following year when Jesse “The Body” Ventura attempted a direct action right before Wrestlemania 2. He later described the incident on the Steve Austin Show podcast:

Two weeks before it, all the publicity had gone out. The advantage was ours. See, Jesse Ventura studies business. The advantage was ours. I stood, I waited, so there weren’t agents around. I stood up in the dressing room and I gave a speech to the boys and this was at the time we were still battling Charlotte [North Carolina – Jim Crockett Promotions], and I said, “if we go together and simply tell the media we are not wrestling unless union negotiators by federal law come in and give us the opportunity to unionize.” [sic] And I said, “guys, the people that turn on the lights in these buildings are union.” I said, “they have to do it by law. It’s in our favor. Then, if we engage the Charlotte guys to do the same thing, we can have a union in wrestling.” I gave this big speech, I left it at there, I went home. The next night, I got a phone call from Vince who basically threatened to fire me if I ever brought it up again and read me the riot act. And I then did WrestleMania 2 and immediately left and did Predator and was a member of the Screen Actors Guild now, my union that I get retirement from now, healthcare from, all of that from. And so, when I came back, I told Vince point blank, “Vince, I won’t ever bring up union again.” And I said, “if these guys are too stupid to fight for their rights, I have my union now. I’m a member of the Screen Actors Guild. I get healthcare, I get retirement, I get everything from them. I’ll pay my union dues [there].”

By his own description, Ventura’s strategy sounded terrible, stuck on the magical thinking that a good speech and righteous cause (and the law) will somehow result in labour power. However, it made perfect sense for a wrestler.

Dave Meltzer of the Wrestling Observer Newsletter has spoken of an old tradition of top wrestling stars refusing to “go on” seconds before a main event they were booked in. Knowing the promoter would make far, far more than any of the wrestlers, a top wrestler could hold up the show and refuse to go on until getting a pay increase to match the size of the audience. This was common enough, continuing well into the televised era but was never done collectively. Ventura’s attempt to turn this old wrestler’s strategy of dealing with the boss into a collective action made sense, but without any organization his plan was doomed to fail.

A deposition later revealed that Hulk Hogan was the company rat who went to Vince McMahon. Following Ventura’s failed action, there were no major drives to unionize pro wrestlers until recent years.

The lone exception to this unorganized industry is in Mexico, where wrestling has been unionized since the 1950s as a way to protect wrestlers from wage theft by promoters and collect dues for pensions. The most significant action was a wrestlers’ strike in 1991 over the repeal of a law banning wrestling on television. At the time, Mexico City had over twenty nightly live wrestling shows and television was seen by the wrestlers as a way to consolidate and suppress audience interest in going out to see wrestling as much. The strike was partially successful and resulted in restrictions on when televised wrestling could air. Afterwards the Mexican union wrestling scene was rent by infighting, from which the union SNL emerged as the only one still standing today. Only wrestlers for the CMLL Lucha Libre federation are unionized under SNL, and it is commonly considered a company union today that takes its share of the gate and offers little in return to its wrestlers.

Wrestling’s history of abuse

At its core, wrestling is a carnival grift and a uniquely American one. It arose in the post-Civil War era as a carnival act to showcase the different forms of folk wrestling around the US. Over time, fixed matches became ‘worked’ matches where the fighting rode a line between real and simulated (which it does to this day). The spectacle moved from carnivals into regional promotions united under umbrella organizations. The NWA formed in the 1950s and worked collaboratively to squash ‘outlaw’ promotions that refused to join, or nationally blacklist wrestlers like Jim Wilson who tried to unionize.

Promoters varied, as do all bosses, but were legendarily exploitative of their workers. Wrestling is rife with stories of wrestlers starting their careers working for almost nothing, being lowballed or cheated by promoters, or being forced to wrestle in appalling conditions or when injured.

One of the sport’s most notorious grifters, the Fabulous Moolah, effectively owned all women’s wrestling in North America for 30 years. After her death in 2007, multiple allegations of terrible abuse sprung up around her. She was the most successful trainer and promoter of women’s wrestling, and sole controller of the NWA Women’s Title. Her trainees were then loaned out to promotions and booked according to Moolah’s wishes, where they would be expected if not forced to have sex with the promoter and wrestlers. Any pay was heavily skimmed by Moolah, who was rarely without the top title she invented and owned.

This and other shadiness is possible because of the incredible secrecy of wrestling. “Kayfabe” is the carnie term for protecting the fact wrestling is a “work” or predetermined, which is protected at all costs, even violently. It has become a kind of wrestlers’ code. Wrestlers also have a strange relationship to trust. Wrestling is extremely dangerous, and as such wrestlers must trust each other in the ring as you are effectively allowing another person to do what they want with your body. Wrestlers routinely call each other “brother” and consider themselves a part of an exclusive club very few get in to. However, the sport is also highly individualistic. Each wrestler is a mercenary looking for the best pay and to get a spot that somebody else wants, which is a culture promoters weaponize against the wrestlers. Unlike in typical combat sports, your place on that card is determined by your ability to sell tickets, not how many matches you win. Drawing power is abstract and difficult to measure, particularly in mid-tier talent, which gives promoters a lot of leeway. If you can’t wrestle, you lose your spot. So you wrestle. So although the close bond between wrestlers is tantalizing for an organizer, promoters have incredible power to destroy a career simply by not booking a wrestler who steps out of line. This culture of fear continues to this day, with wrestlers working during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic out of justified concern about retaliation.

Wrestling is also not easy. Wrestlers peak in their mid-30s, a good ten years later than in other athletic sports because of how difficult it is to beat somebody up and make it look fun. Everything in a wrestling ring hurts. When wrestlers began to ‘work’ matches they learned that to make a punch look real, you have to really hit someone. A wrestling punch makes full contact, unlike an actor’s punch. The ring is a wooden platform with thin padding. The ropes are elevator cables and hurt like hell to bounce off of.

Wrestlers work constantly as well. This leads to a high rate of injury, particularly when wrestlers are trying to prove themselves. An injury, a family emergency, basic illness, or upsetting the promoter can cost you everything. Thus, wrestlers often work injured and wind up turning to drugs or alcohol to manage the pain of fighting to keep their top spot. A wave of this behaviour in the 80s and 90s led to a huge number of early wrestler deaths, particularly in the mid-00s.

All of these factors combine into an industry that is (like most) hard to organize. There’s no evidence that unions ever seriously looked at wrestling during its territory days. It was – and to some extent still is – insular and individualistic, with wrestlers moving all over the place, where selling one another out is a normal part of the business.

In the 1980s, the WWE (then WWF) was purchased by Vince McMahon Jr from his father. McMahon broke the longstanding rule of not promoting in someone else’s territory. He used new technology like closed-circuit which allowed fans to travel to event centers and watch Wrestlemania on a huge screen, and the explosion in cable television to create wrestling’s first truly national product. The great wrestling boom of the 80s saw the territories bought up by WWE. All the while, stories of drug abuse and sexual exploitation dogged the company. WWE defeated its main rival WCW in the 1990s and has remained nearly the only name in wrestling until today. Throughout its tenure as top promotion, there has been virtually no talk of unionization since Ventura’s failed action back in 1986.

Nowadays, there are legions of retired wrestlers who speak candidly about the once-secret days of the wrestling business, particularly as they have seen so many of their colleagues die from the long-term effects of drug abuse. Calls for a union come regularly as they now look to their own futures with many of their colleagues dead from hard living, and no pension or capacity to pay their own health care bills. Just recently “Super Genie” Melissa Coates, a minor women’s star from the 90s, had a leg amputation that she has started a GoFundMe to pay for. Such news is common in wrestling circles.

Organizing wrestlers today

Wrestling is in a very different place now than it was during the territories. Nowadays wrestlers are premier athletes with multi-year long contracts, with top stars netting millions of dollars. However, wrestling’s carnie ethos and exploitative management practices are still there. WWE has a constantly touring live show — the life of a wrestler is like a rock band that never stops touring 300 days a year while getting punched in the face for real. Thanks to strong political connections (Vince McMahon’s wife Linda is the head of Trump’s largest PAC), WWE has managed to classify their employees as independent contractors in way that works only to the advantage of the employer. As independent contractors, WWE wrestlers are expected to pay for their own health care, training, most travel, food, insurance, hotels, costumes, and so forth, as detailed in this copy of Chris Benoit’s contract from 2006. However, their rights are solely owned by WWE and they cannot work for another company while on contract, or for an additional 90 days after their contracts are terminated. Wrestlers can’t even quit their jobs and must work for the WWE for the entire duration of their contract, which is of course extended if they are injured. Former wrestlers have sued WWE over this status, which was unsuccessful despite the obvious abuse of the contractor status.

However, with corporatization of wrestling, the culture has also significantly changed. The newest generation saw the wave of deaths fifteen years ago and are predominantly clean-living athletes with college educations who spend their evenings in the hotel playing video games rather than at the bar. Wrestling fans have changed too as the sport has lost many of its blue collar fans and instead become a favorite hobby of online geeks.

The endless online discussion of wrestling means that complaints about wrestlers as independent contractors is old hat. John Oliver has covered it, and Andrew Yang has recently made it a key cause of his, one he hopes to address in the Biden administration.

Younger wrestlers themselves have begun to push for unionization more openly, most notably David Starr. The upcoming star in the UK wrestling scene openly spoke about unionizing and other left causes but as a top talent continued to be booked. This all collapsed when he openly held a training clinic on how to unionize and was promptly blacklisted by WWE, which has become a major power in the UK. Starr later had his career legitimately destroyed under a wave of abuse allegations in the UK’s #SpeakingOut movement about sexual abuse in wrestling. Appropriately, this led to the union he was working with, Equity UK, to sign a code of conduct with EVE’s Riot Grrls of Wrestling. Notably, this was spearheaded by EVE’s owners. It’s unclear whether Starr’s attempts to unionize have resulted in any improvements for UK wrestlers.

To date there is no information showing greater collective power over the employer on the part of wrestlers in the UK or US. Jesse Ventura came the closest, and his idea of organizing was one good speech.

This leads us to Zelina Vega’s release.

The Covid-19 pandemic shut down WWE’s live tours, and as such left a huge number of wrestlers without that income source, and bored at home with only television shows to work at once a week. This led to a proliferation of wrestlers starting streams on Twitch.tv where fans can subscribe to watch wrestlers play video games or just engage with their audience. Many of these accounts have been extremely successful, particularly for lower-paid women’s talents such as Vega and Paige. Vega in particular made more money on Twitch than she did from her WWE contract. Although wrestlers can make significant money, lower-card women may make under $100,000 a year despite the incredible expenses involved with the job.

Paige is a special case, a wrestler born into a UK wrestling family who has been wrestling since she was a teenager. In recent years her career was cut short with neck injuries before she suffered a leaked private photos scandal and fell into a horrifically abusive relationship. She was recently the subject of the movie Fighting With My Family, which Vega also starred in. WWE still employs her as Paige has garnered tremendous goodwill from her recent movie and well-publicized traumas. Releasing her would be a PR disaster.

WWE recently passed down an edict that all talent must cease their Twitch streams, under the likely plan that WWE would re-open their own streams where they would take all the subscriber fees and grant the talent a portion of the money. Wrestlers were furious. Says Paige:

“I’ve honestly gotten to the point where I cannot deal with this company anymore. Now I have to make a very important decision. I’m fucking tired, man. I broke my fucking neck twice, twice for this company.”

Several stars appealed to Vince McMahon as a group but failed to change his mind. Paige and Vega defied the company order and kept streaming, and Paige began publicly talking about unionization on twitter with Vega chiming in. Vega confirmed she was making more money streaming than she was for WWE. Finally, she opened an Onlyfans account (where fans can pay for exclusive pictures), which was also prohibited, and was fired. As a final grenade over her shoulder, she managed to time her tweet about unions just as her release was announced.

It worked, and the tweet went viral, kickstarting widespread talk about why wrestlers need a union. In the past, wrestling has been too focused on live events for SAG-AFTRA to invest, and too televised for Actor’s Equity. However, SAG-AFTRA has now openly stated they will look at WWE.

Wrestlers can, and should organize

Whether or not SAG-AFTRA will certify wrestlers is unknown, but the path has just been explained by a board member on the popular Wrestling Observer Live show. The growing crossover between wrestling and acting is significant and more and more wrestlers are eyeing a post-wrestling career in Hollywood. However, wrestling is not acting, nor is it exactly sports. It is best understood as a performance art, and who knows what union would get the cert for that. Regardless of where they may end up, it is obvious that basic union benefits like a pension and health care would make an enormous difference in wrestlers’ lives.

To get there, the wrestlers must stop falling into the mistakes that doom so many union drives. You cannot shout UNION publicly as Paige did, and then hope a pension plan shows up. Celebrities can easily mistake the adulation of fans for a form of power over their boss – history has shown that power is marginal. Their true power is in their work, or refusal to do it. WWE currently airs three live television shows every week and has returned record profits during the Covid19 pandemic thanks to deals like the one struck with Fox. The networks must be kept happy. That makes WWE vulnerable. Wrestlers should remember the federation’s old motto: “anything can happen.”

Jesse Ventura had the right goal, but he had no idea how to get it. He outed himself as a target, didn’t have any personal conversations, and failed to identify and isolate rats like Hulk Hogan. The strategy for organizing a workplace can be followed in any wrestling company. If wrestlers want to join SAG-AFTRA or leverage their boss to get their Twitch accounts back they need to learn to keep secrets and talk to people one at a time. The best, most classic wrestling matches are one-on-one. That’s how you do it. Keep the code. Kayfabe. Work together and develop that trust with each other like in a ring. Don’t shout what you’re doing to the damn fans, because they can’t organize for you and they don’t have the power against the boss that you do. Grab a headlock, and whisper what happens next, so nobody notices. Do that until you know exactly who is on side. Write the next part of the script collectively, deciding what to do (or refuse to do) next and when. Like a good wrestling match, don’t go too fast but find the right pace so you get maximum effect at the correct time. The old carnies knew a hell of a lot about how to get a dime out of the fans, now wrestlers need to use what they learned to get that dime back from their bosses.

Dave Powell is a lifelong wrestling fan who met his wife on an online fantasy wrestling forum. He is also the President of the Athabasca University Faculty Association.