A teacher in Cleveland Heights describes an unusual turn of events during recent contract negotiations.

Employers will go out of their way to undermine workers’ exercise of power and negate worker agency. But one school district on the edge of Cleveland took that to a new level by pretending that a strike wasn’t even happening.

Cleveland Heights-University Heights is an economically diverse inner-ring suburb. There are million-dollar homes, and subsidized housing a short walk away. While the district is very diverse, the schools are not. The affluent and even many middle-class parents send their children to private schools. Since the state of Ohio created Ed Choice vouchers, those parents can raid the public schools’ coffers to help pay for tuition at the school of their choice, taking up to $6,000 out of their child’s designated school, regardless of whether the student had ever attended. The result is a public district that is high poverty, mostly minority, and deeply underfunded in a liberal island of independent shops, “no nukes” stickers and people bicycling to work.

The Cleveland Heights Teachers Union sought to negotiate a new contract in this economic morass, but this time things took a turn. The teachers had not been on strike in this town since 1983, having continually pushed for labor management peace and shared governance as guiding principles. Further, the teachers have had a habit of sacrificing pay raises for better health care. This is not a firebrand union. But this is 2020 and nothing is normal.

A new superintendent would be on the other side of the table for bargaining sessions. The district delayed for months. At the first meeting in June, they opened with an offer that drastically increased health care costs — by 250% — while slashing the quality of the plan. Ironically, they cited COVID-19 as the reason to cut health care. The teachers counteroffered, but the board closed discussions. After weeks of negotiating sessions with a federal mediator, in September the board declared their first offer as their last, best and final offer. Then they took the unusual step of imposing the contract on January 1, 2021. To add insult to injury, they filed an Unfair Labor Practice against the teachers for not bargaining in good faith. It seemed that the very idea of meeting teachers as equals to bargain fairly meant acknowledging worker power, and they would not do that.

The teachers convinced the reluctant board to put a school levy on the November ballot, which they did. The district and teachers agreed to a truce in an effort to get the levy passed so that they could negotiate with more economic breathing room. The levy passed by less than one percent. When the teachers sought to reopen negotiations, the board refused. They were adamant that their offer was the only offer that would be entertained. The teachers took a strike vote and 97.5% agreed that the imposed contract should be rejected. The Friday before Thanksgiving, the teachers’ union gave their legally required 10 days’ notice to strike, which would put teachers on the picket line on December 2 for the first time in 37 years.

Within minutes of the strike notice, the district launched their strike plan. They had prepared threatening letters for teachers, and lined up scab contractors. One of the first talking points on the letter was that any teacher going on strike would immediately lose their health care benefits. Citing an Ohio law that gives school districts the option to suspend pay and compensation (benefits) in a strike, they presented it as a requirement. Removing a family health care benefit by choice during a pandemic seemed like the 19th century tactic of evicting striking workers from company housing during poor weather. In a Zoom board meeting, the board president broke into tears when voting to end benefits. This set the community on fire. They weren’t buying the narrative, and they weren’t accepting the administration using health care benefits as a club against workers. General Motors had tried to do the same thing last year and backed off due to public pressure. Besides, this community had just passed a school levy to avert a labor stoppage and the district was coercing teachers. Letters, phone calls and emails came in from around the country, but the district did not budge.

As the zero hour got closer, the district realized their push to bring teachers back was not going to work. Further alienating the community, they suspended all special education services during the strike. Their plan to hire infamous strikebreakers Huffmasters to staff the classes wasn’t working either: they had entire middle schools with only 11 teachers for all students. The community understood that with the new contract and levy they would be paying more and receiving less because the district did not want to negotiate with the teachers. The pressure campaign on the district was beginning to get some results. On December 1, less than 12 hours before the pickets were to begin, the district began actually negotiating for the first time.

This district sits in the Great Lakes Snow Belt, and the morning of December 1st delivered ten inches of snow. But since the schools are all remote, it did not impact classes. There are no snow days for remote school. By the morning of the 2nd, the snow was done. Teachers arrived at 7am to begin shoveling the sidewalks that the district had not plowed, and picket lines outside of empty buildings began half an hour later. Teachers brought clever signs from home or dutifully collected the local’s pre-printed picket signs — ones that had been in storage since the 1983 strike! It was quiet and cold, punctuated by sharp car horns of support that earned smiles and waves back. Throughout, everyone was checking their phones for updates from negotiations.

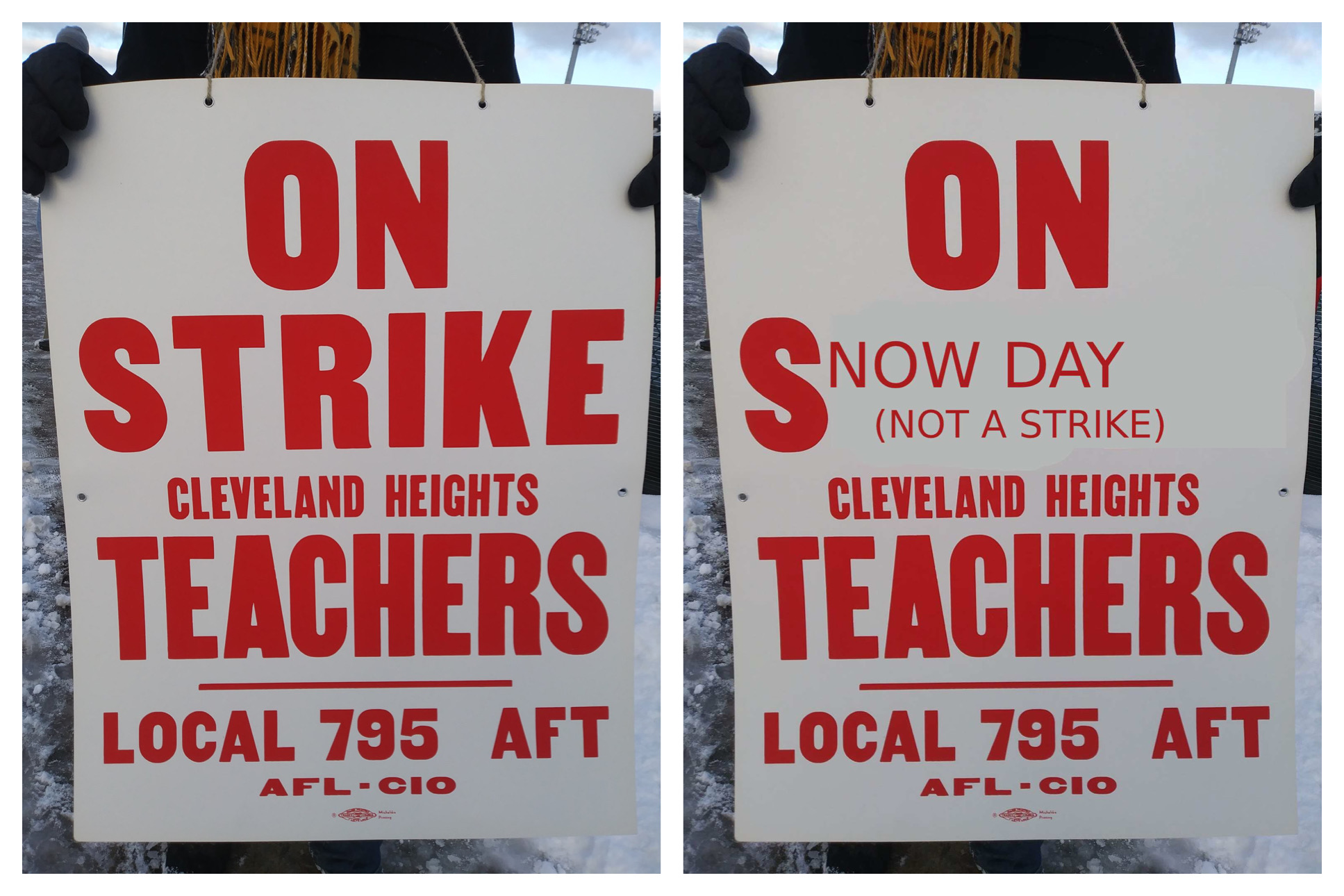

Then a loud laugh rolled down the line as teachers saw the district had cancelled school for the day due to inclement weather. They speculated about whether this meant that they would be paid for the snow day. Spirits were high. As the buildings were empty anyway, in calling a snow day the administration was attempting to remove the efficacy and legitimacy of the picket line. However, the consensus on the line was that this was a strike, and the results that came soon after were pretty obviously not the consequence of a snow day, but of collective action.

Three hours after striking, a message went out to all teachers that there was a tentative agreement and to break off the pickets and meet on Zoom at noon. The contract would be concessionary on health care, but only about 20% as damaging as what was to be imposed. Essentially, it would be a break-even contract overall for two years.

But the district wanted so badly for this to not be a strike that they declared two unnecessary snow days — December 2nd and 3rd would be paid days during which teachers did not have to work — and paid the teachers for the time spent on the picket line. The press release even claimed that a negotiated agreement was finished by 7:30 AM but some teachers just had not heard and so mistakenly showed up to picket (yeah, about 470 of 500!). Just like in negotiations, it was important for the district to be in control. The changes to the contract were not because teachers took action, but because the district had decided to make changes. In not challenging that narrative, the local was able to secure paid time that actually cost the district more in salary than they clawed back from membership in austerity cuts to benefits.

Whether it was a snow day or a strike is not just semantic, but a reflection of a deeper struggle over power, including narratives about who has it. The teachers understood well that their actions were the reason for a significantly better (but still bad) contract. By going on strike for the first time in 37 years, the local of 500 teachers had blazed a new pathway after decades of dormancy.