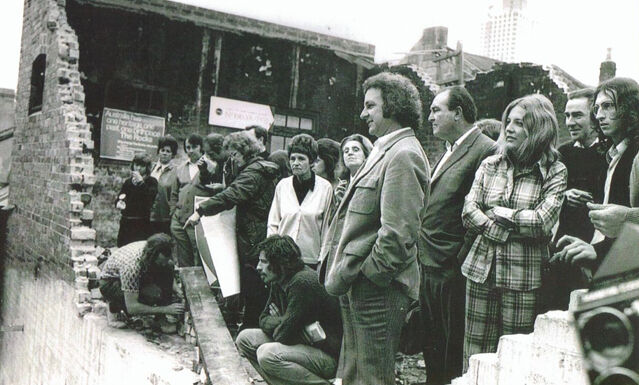

Ben Purtill recounts when building laborers in Australia stopped work, first over wages and working conditions, and then to protect the environment, among other “social” causes. Image: Jack Mundey, Building Labourers’ Federation members and local residents at a Green Ban demonstration, 1973.

Jack Mundey, who died aged 90 in May 2020, first made his name as the union leader associated with one of the most inspiring moments of class struggle of the last 50 years: Australia’s green ban movement. As a secretary of the New South Wales Builders Labourers’ Federation (BLF) from 1968, Mundey — a member, then president, of the Australian Communist Party (CPA) – was widely credited with coining the term “green ban” to describe a form of strike action undertaken in defense of environmental causes. Members of the NSW BLF also downed tools in defense of the gay community, indigenous Australians, and feminists, at a time when these causes were far from the mainstream of Australian society.

Reviled and vilified at the time, Mundey received a State Memorial Service in March 2021. Attended by the great and the good of Sydney, Mundey was hailed as a savior of the city — a renegade who broke with the base concerns of economistic trade unionism to focus on more refined issues than wages or workplace conditions, while prefiguring a social liberalism the nation would only begin to embrace decades later, and a green politics that it has yet to.

While the perceived content of Mundey’s unionism now sits quite comfortably with liberal — even conservative — values and principles, the form of unionism pursued by the NSW BLF at their peak in the early 1970s would undoubtedly be condemned were it revived today. Militant, democratic and regarded as quasi-syndicalist by critics and supporters alike, the story of the Mundey and the NSW BLF is one of both the power of the rank and file and the limits of leadership, no matter how left-wing.

Black Bans, Green Bans and everything in between

Most historical accounts suggest the green ban movement for which Mundey is best remembered began in 1971 at Kelly’s Bush, an area of parkland in Sydney’s affluent Hunter’s Hill suburb. A group of local women contacted the BLF having exhausted all conventional means of halting the development of the area by construction firm AV Jennings. With luxury houses set to be built on what was the last remaining patch of native bush in the suburb, the BLF called a community meeting attended by over 600 local residents and announced a ban, meaning no work would take place on the site. Unions had been using the term “black ban” to designate disputes aimed at an economic end, for example a wage increase, but since this action was being taken to defend the environment, “green ban” was decided to be more appropriate.

Over forty green bans followed until 1974, when the NSW BLF was deregistered as a union, resulting in billions of dollars worth of development being prevented in Sydney; the tactic was also deployed in other towns and cities across Australia, most notably Melbourne. All green bans were declared in a similar manner as a point of principle: the union did not decide to initiate a ban, local residents did so through a public meeting. If it was decided that a site would not be developed, BLF members would not work on it. In following this tactic, large areas of the historic centre of Sydney were saved from development, and the union joined alliances with an unlikely range of characters: early environmentalists, heritage campaigners, and middle-class homeowners.

The NSW BLF also applied the tactic to other causes and concerns, for example the expulsion of a gay student from Macquarie University, the demolition of houses occupied by indigenous Australians in the Redfern suburb of inner-city Sydney, and the right of two women academics to teach a women’s studies course. In each case, the campaigns were won. More broadly still, the BLF campaigned against apartheid South Africa and the war in Vietnam. As union secretary of the NSW branch during this period, Mundey is now typically remembered as the brainchild of this movement, even earning him a speaking slot at the United Nations Conference on the Built Environment, but it reflected much wider changes occurring both within the Australian left and among rank and file union members.

Communist splits and class reawakening

In the ten years preceding emergence of the green bans, the CPA had undergone a series of significant splits, resulting in three separate parties, each with a degree of influence in the union movement, within both the union bureaucracy and rank and file. The first was over the Sino-Soviet split and saw the formation of the Communist Party of Australia (Marxist-Leninist) (CPA-ML), not itself unique for the period; less normal however was the CPA leadership strongly condemning the Soviet response to the Prague Spring, eventually leading to a split and the formation of the pro-Soviet Socialist Party of Australia. This left the CPA a free agent at a time when revolution seemed to be in the air, with the party’s leadership keen to embrace the trends emerging from university campuses, the antiwar and women’s movements, and counterculture more broadly. So keen, a party newspaper once positively reviewed an Abbie Hoffman book.

In this context, it becomes tempting to understand the NSW BLF as a function of a liberalizing official Communist Party inspired by the New Left. After all, Mundey and other key members of the NSW branches’ leadership were CPA loyalists, and many of their actions were entirely consistent with the direction the party was taking at the time. In turn, the eventual demise of the union’s NSW branch receives an even easier explanation: a sectarian struggle between the Maoist federal leadership of the BLF under the general secretary Norm Gallagher (CPA-ML), who sided with the state, developers, and the Master Builders Association in choosing to expel the NSW BLF leadership.

Yet while a global ‘68 undoubtedly influenced the development of the NSW BLF, the heating up of industrial militancy at home was of greater importance. In 1969, Clarrie O’Shea, Victorian Secretary of Australian Tramways Union and leading member of the CPA-ML, was jailed for refusing to acknowledge a court order that the union pay over $8,000 in fines under the penal sections of the Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Act, the law that controlled industrial relations until it was superseded in 1988. O’Shea’s sentencing led to strikes across Australia, with 500,000 workers in Victoria alone taking part in strike action, effectively paralyzing the state. He was released after six days, and though the laws used against him were not revoked, the penal powers were never used again.

The victory of the movement against O’Shea’s jailing, an expression of a much wider movement against compulsory arbitration laws, opened an opportunity for more militant unionism. Union officials of both right and left — indeed, of the “extreme left” — often used penal powers as a reason to urge militant workers back to work, such that many workers could not tell the difference between officials from the right, left or centre. In Mundey’s own words, an “arbitration mindedness” meant that conflict was avoided at any cost, and giving it a left sheen often simply meant justifying it as being “in the interests of the class as a whole.” In the 1960s there was an average of 1,341 disputes per year, with an average of 86,2000 work days lost to industrial action; in the 1970s, there was an average of 2,368 disputes per year, with 314,6000 work days lost. Like the USA, the UK, and much of western Europe, Australia also had a long, hot 1970s.

Union democratization

The BLF stepped into this long ’70s a different union to the one it had been even a decade earlier. Some twenty years had been spent by rank and file activists — Mundey among them — to reform one of the most corrupt, right-wing unions in one of the most dangerous and poorly paid industries in the country. Some accounts claim that BLF organizers in the early 1950s were paid from site to site to turn a blind eye to safety conditions, with workers who did complain often being on the receiving end of violence. The fact that builders’ laborers were unskilled and casually employed made the process of democratization harder — members were more likely to keep their heads’ down and move on to another job or industry than challenge the prevailing conditions, including union corruption.

Changes to Australia’s political economy helped those rank and filers fighting for reform: the same construction boom that spurred the BLF to take action against development had grown the ranks of the union in the late 1950s and early 1960s, while bringing workers closer together on the job. Previously laborers would typically work on smaller suburban sites spread out across Sydney’s sprawl, but increasingly they were brought together on larger, more complex Central Business Districts sites — much more dangerous but with much scope for disruption (downing tools during a single concrete pour could end work for days, for example). With the stakes far higher and opportunities even greater, the continuation of the corrupt, business-as-usual BLF became untenable.

By the end of the 1960s the process of democratization brought unthinkable changes to the BLF: limited tenure was introduced for officials, who did not receive payment during strikes, and whose wages were tied to that of members; mass meetings were held — often on the job — with interpreters present for the many recent migrants among the unions’ rank and file; elected strike committees ran strikes, including the formation of “vigilantes” that moved from site to site to destroy the work of scab labour; members had access to the unions’ financial records, and significant say over all union matters. The results spoke for themselves, with substantial wage increases won throughout the early 1970s, and conditions that were once practically Victorian finally brought into the twentieth century.

The success of the BLF over “bread-and-butter” campaigns, and the power handed to workers in managing the affairs of the union, went hand in hand with the action that was taken for social or political ends. With wages and conditions improving, so too was confidence. As strike action was now a regular, almost daily occurrence for members, taking action over issues with less tangible or immediate benefits was less daunting — it was another instance of downing tools and winning. However, the extent to which this aspect of the BLF’s militancy was led from above remains open to question. When the NSW BLF was ultimately deregistered as a union in 1974, the federal leadership denied that it was over the green ban policy — which was policy of the entire union — but “adventurism and irresponsibility” at a leadership level. Now members would have the choice of joining the new, federally-run union formed in agreement with the Master Builders Association or face an immediate lockout. The NSW leadership recommended the former course of action.

Mundey’s misremembered legacy

In the collective popular memory drawn upon both to memorialize Mundey and celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the start of the green ban movement, the BLF was a moment of Australian flower power, a legacy of the late 1960s that married the concerns of counterculture with the blokey machismo of builders’ unionism, thus softening the latter. Militant rank-and-file disruption on the job doesn’t fit so easily into this popular image. But if Mundey died a hero of those who might have otherwise despised him and all that he represented, it’s not simply because time has a habit of softening feelings.

Taken out of context, of course the notion of a union of laborers striking for socially-oriented causes appeals to middle-class liberals — even more so when it often involved members of the middle class and working class lining up side-by-side. If industrial militancy is a menace when it is concerned with economic demands, it appears to be a lot friendlier — almost quaint — when it is used for saving heritage buildings or grassland. This was a calculation Mundey appeared to be well aware of, and one that operated entirely within the CPA strategy of the time.

Yet for a few short years in the early seventies, the BLF also demonstrated that class power has the potential to remake society, that the organized working class can decide questions far greater than the limits imposed by laborism, which seeks to police the legitimate concerns of the class (wages and conditions) from the illegitimate (the nature of society), and that economic and political questions are intertwined in the class struggle.

Ben Purtill is an amateur labor historian living in Australia.