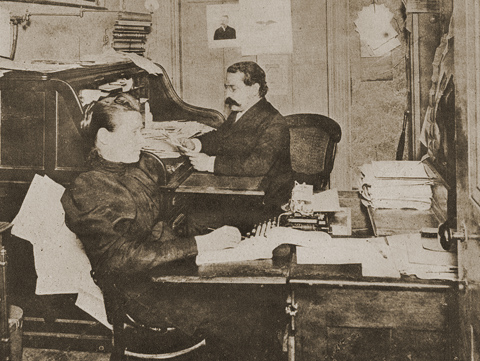

This is part three of our series examining the origin of paid staff and paid union officers, by labor historian Robin J. Cartwright (the name is a pseudonym). In this segment, he shows how early AFL unions came to rely increasingly on paid, professional staff as contracts and union insurance plans proliferated, and union finances stabilized. Read Part I of the series here and Part II here. Image: Samuel Gompers in the office of the American Federation of Labor, 1887.

At the end of the 1870s, a group of trade union activists, including cigar maker Samuel Gompers, pledged “under no circumstances will we accept public office or become interested in any business venture of any character or accept any preferment outside of the labor movement.” Noting that many previous labor leaders had drifted out of the labor movement, they swore to “devote our entire activity and influence to the labor movement and in furtherance of the interests and welfare of the toiling masses.” Thus, in the aftermath of the 1877 great strike and the end of the 1870s depression, the Knights of Labor were not the only union determined to rebuild the labor movement. Craft unionists also began organizing international trade unions, either by establishing new unions or by reviving moribund organizations. Initially dwarfed by the Knights, they grew to a combined membership of 100,000 in 1890 and after that overshadowed the KoL. In their early years, these trade unions relied primarily on volunteers and kept paid employees to a minimum, but over the course of the next thirty years they gradually expanded the ranks of full-time paid officers and staff. This change was a byproduct of other policies pursued by the trade unions, including signing contracts with employers, stabilizing membership numbers & union finances, and offering insurance benefits to members.

In the late nineteenth-century, it became increasingly common for labor organizations to negotiate contracts with employers. Unions have not always signed contracts. Prior to the 1880s, labor relations were highly unilateral. Employers would impose changes by fiat and refuse to negotiate except on an individual basis. Labor unions would issue demands and strike (or use other actions) to make employers grant them. Formal negotiations often did not happen, and were generally minimal and piecemeal if they did. When things were put in writing it did not take the form of a comprehensive document covering all disputes for a fixed amount of time. In the 1880s, the Knights of Labor championed a greater level of negotiation but without signing contracts, arguing all disputes should be resolved by arbitration. Employers generally refused to arbitrate matters except where the union was extraordinarily powerful and could force them into it.

Local contracts signed by AFL affiliates began slowly proliferating in the late 1880s, and they negotiated several national contracts in the early 1890s. Contracts are comprehensive written agreements between management and the union that last for a specific amount of time and settle disputes on a variety of subjects. The earliest contracts, and almost all subsequent contracts, contained no-strike clauses; unions could not negotiate a contract and then go on strike the next day demanding something different from what they had just agreed to. In the early twentieth century, the practice of signing and administering contracts became the dominant form of labor-management relations. In 1918, the economist and pioneering labor historian Selig Perlman noted, “at present the trade agreement [contract] is one of the most generally accepted principles in the American labour movement. It is professed by the ‘pure and simple’ trade unionists and by the great majority of their socialist opponents. Those who reject it are a very small minority composed principally of the sympathizers with the Industrial Workers of the World.”

The transition to contractualist unionism had the effect of encouraging unions to employ their officers on a full-time basis and hire full-time staff. Formulating, negotiating, administering, and interpreting contracts is a labor-intensive activity that requires mastering a specialized body of knowledge and developing specific skill sets. Many contracts are long, complicated, and written in obscure legalese. It is easier to navigate the world of contracts as a professional who can devote your whole working time to it than as an unpaid volunteer in your spare time. Full-time professionals can improve their skill at handling contracts, and become real experts, at a faster rate than volunteers because they spend their entire work week on it while volunteers can only spend a few hours a week.

The reverse applies as well: once a union has full-time officers and staff, it is more likely to start negotiating contracts, as they already have the union professionals needed to do so. Signing contracts and employing union professionals were thus mutually reinforcing trends. Contractualism encouraged AFL trade unions to employ more union professionals, and employing union professionals then encouraged AFL trade unions to sign even more contracts and eventually make it the standard way of doing business.

The same process also encouraged contracts to become larger and more complicated. The more convoluted the contract, the more the union needed professionals to negotiate and navigate it. Union professionals thus tended to allow contracts to drift in a longer, more complicated, and legalistic direction. That drift usually was not the result of a sinister conspiracy, but a byproduct of union practices. If one accepts that union professionals are good for the labor movement, then practices that heighten the movement’s dependence on them (such as long and complicated contracts) are themselves good for the movement (or at least neutral) because they encourage unions to employ needed professionals.

Another reason for the growth of paid labor inside trade unions was their improved finances and growing membership. In the late-nineteenth century, many unions instituted measures to stabilize their membership and thus their income (which almost always came from dues paid by members). Those measures included the closed shop or union shop, the inclusion of insurance as a benefit for all members, high initiation fees, and the union label. Closed shops and union shops ensured the union was able to retain members by making union membership a job requirement. Even if a worker would otherwise leave the union and stop paying dues, they maintained their membership in order to keep their position. Insurance had a similar effect: workers who would otherwise drift out of the union kept paying dues so they could benefit from union sickness, death, and/or out-of-work benefits. High initiation fees also deterred leaving the union, as they made it cheaper to continue paying dues rather than leave the union and possibly rejoin again at a later date. Union labels meant a certain portion of the market would produce union-made goods, which insured unions would retain a certain portion of the workforce as members.

None of these measures were completely new. Some of the earliest craft unions had death benefits and/or closed shops, but these were not employed on a widespread scale. Even though some Knights of Labor locals had closed shops, most did not. Terence Powderly, leader of the KoL, devoted a chapter of his autobiography to criticizing the closed shop, arguing that forcing workers to join unions when they were hostile or indifferent weakened the labor movement. What changed is that trade unions began instituting these measures on a larger, more systemic, scale. They did so deliberately with the intention of attracting and maintaining a larger and more stable membership.

As mentioned, a byproduct of a larger and more stable membership was that unions could now afford to hire staff and officers on a larger scale than ever before. A union with little funds cannot hire anyone, while a union with wildly fluctuating membership numbers might be able to hire people temporarily but will be forced to let them go after its finances take a turn for the worse. Stable and large union finances are a prerequisite for turning union positions into a profession.

This process also worked in the reverse. Once established, union professionals had a vested interest in ensuring the union continued to have a large, stable income, to ensure it could continue to afford to employ its staff and officers. Consequently they and their supporters tended to campaign for measures that maintained membership and secured financial stability. These actions were not necessarily motivated exclusively by selfishness. If one believes it is good for the union to employ staff and pay its officers, it follows that measures which ensure it can consistently afford to do so are also good for the union.

The bundling of insurance with union membership, meant to maintain membership when it would otherwise fall, was itself also a reason why the use of paid labor by trade unions expanded in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. If only a few members file claims for benefits, that can be administered by volunteer officers, but once insurance programs exceed a certain size the union will need to hire people to administer them, process claims, and manage the money.

As the reliance on paid officers and staff grew, it created a feedback loop where the bureaucracy expanded to meet the needs of the expanding bureaucracy. The growth of paid labor in one part of a union created a precedent that was cited to justify expanding paid labor in other parts of the union. It established a stratum of union professionals with a vested interest in expanding the use of paid labor so as to secure their own jobs and create greater opportunities for career advancement. Union professionals, like most other professionals, generally attempt to convince others that they are reasonably competent at their job and the position itself is worth the money paid. Failure to do so risks being fired or otherwise disciplined, or even the abolition of the position. Success in doing so can lead to praise, raises, and promotions. In a union job, that means doing work that cannot be easily done by volunteers, which creates an incentive to expand that type of work. Union professionals thus have a tendency to increase the total volume of union work, reorganize it, and/or make it more complicated, so that it cannot be easily done by volunteers.

Finally, although the growth of paid labor in trade unions meant the conversion of officers into full-time jobs, it usually did not significantly increase the total number of officers. Officers generally preferred to increase the number of subordinates rather than the number of rivals, and so established hierarchies of paid staff rather than allowing the number of officers to proliferate.

This article will show that the AFL and its affiliates initially continued the tradition of keeping paid officers and staff to a minimum and that signed contracts, stable union finances, and union insurance benefits caused them to gradually transform into unions that heavily relied on paid officers and staff, turning union positions into long-term careers for the first time in history.

The Early Years

Arguably the most influential trade union of this era was the Cigar Makers’ International Union. Founded in 1864 by a convention of local cigar workers’ unions, the CMIU was initially named the National Cigar Makers’ Union, but changed its name in 1867 after some Canadians joined. Membership reached 5,900 in 1869, but dropped significantly due to the onset of the depression in 1873, declining to 3,771, then to 1,016 at the start of 1875, and finally to around 500 at the end of 1875 after losing a strike. Most labor unions did not survive the 1870s depression, and the CMIU could easily have died as well.

Several CMIU activists made a commitment to reorganize and rebuild the union, the best known of which were Samuel Gompers and Adolph Strasser. Gompers immigrated to the United States from the United Kingdom as a child in 1863. As a young man in the early 1870s, he sympathized with Marxism, but soon drifted away from it and towards what he would later call “pure and simple unionism” – the idea that unionists should organize for better pay and working conditions within the current system rather than seeking the overthrow of capitalism as the long-term goal of the labor movement. Until the twentieth century, Gompers usually voted for left-wing third parties in Presidential elections. He was offered a well-paid position with the Treasury Department in the late 1870s, but turned it down because he wanted to focus on building the labor movement.

Adolph Strasser immigrated from the Austro-Hungarian empire in 1872, after which he befriended Gompers and joined the International Workingmen’s Association (“First International”) led by Karl Marx. He would later be active in the Social Democratic Workingmen’s Party of North America. Strasser remained a socialist longer than Gompers, but also abandoned it for pure and simple unionism by the 1880s.

Strasser and Gompers first attempted to revive the CMIU in their home of New York City and then shifted their focus to the International. The CMIU convention elected Strasser Vice President in 1876, and then President in 1877. In 1875, local 144 in New York City elected Gompers president; he would also represent it as a convention delegate several times. In 1880, with Strasser’s support, Gompers was able to push through a set of reforms centralizing power in the national leadership, significantly increasing dues, and providing all members with life and health insurance. The previous year’s convention had already decided to offer members loans to help with moving expenses when taking a union job in a different city, and later, in 1890, it would also provide all its members with unemployment insurance.

Gompers’ changes were meant not only to rebuild the union but also to insure it would survive future challenges. He wrote:

A problem which demanded our thought from the beginning was how to stabilize the union … we had to do something to make it worthwhile to maintain continuous membership, for a union that could hold members only during a strike period could not be a permanent constructive and conserving force in industrial life… An out-of-work benefit, provisions for sickness and death appealed to me. Participation in such beneficent undertakings would undoubtedly hold members even when payment of dues might be a hardship… Developing financial strength was the foundation of stable unionism. Cheap unionism we were convinced did not contribute to stability or effectiveness… As protection to the benefits proposed we recommended that every union obtain permission from the Executive Board before inaugurating a strike.

For most of the nineteenth century, union membership fluctuated wildly, with workers joining unions during periods of intense conflict and drifting away when conflict subsided or high unemployment made it hard to gain concessions. Gompers wanted to put an end to this pattern. Insurance benefits were provided to all members in good standing, so long as they continued to pay their dues and satisfy membership requirements, even if they were out of work, were not covered by a union contract, or did not work in a factory with a closed shop.

In 1882, with Gompers’ support, President Strasser invalidated the election results in Local no. 144 in New York City to keep his local supporters in power. The opposition, largely made up of recent immigrants who did not speak English, was led by members of the Socialist Labor Party who disagreed with Gompers’ and Strasser’s lobbying tactics. They appealed Strasser’s decision to the International Executive Board, which visited New York City to investigate and then ruled against him at an in-person meeting. Gompers and Strasser refused to accept the board’s ruling, claiming it was unconstitutional on the grounds that “the constitution of the International Union provided that the Executive Board’s business should be transacted by mail or telegraph and made no provision for any [in-person] Executive Board meeting.” The CMIU then split, with the opposition forming the Cigar Makers’ Progressive Union, which enrolled two-thirds of all cigar makers in New York City at its height. Initially, the CMPU was aligned with the Knights of Labor, but they later fell out and New York City was the scene of three-sided union competition in early 1886. Later that year the CMPU agreed to dissolve and its locals re-affiliated with the CMIU.

Despite this split, Gompers’ reforms were ultimately successful at attracting and retaining members. CMIU membership increased from about 1,000 in 1877 to 24,000 in 1890 to 43,837 in 1910. It went from 17 locals in 1878 to 276 in 1888. The CMIU became a model, copied by many other craft unions. At the time it was called the new unionism. Later generations would call it business unionism.

One of the unions influenced by the CMIU was the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners, which chose to offer a less generous version of its insurance benefits. For its first twenty years the Carpenters had only one full-time paid international official, their Secretary-Treasurer Peter J McGuire. McGuire met Gompers at school, and they remained lifelong friends. As a young man, he joined the First International, although he preferred Ferdinand LaSalle to Karl Marx. At the start of the 1873 depression, McGuire joined a radical group named the Committee for Public Safety, which organized demonstrations for unemployment relief (the Committee for Public Safety was also the name of the government agency in charge of guillotining people during the 1789 French Revolution). He led a sit-in at a police station demanding the Committee be permitted to hold a protest in Tompkins Square Park, prompting his own father to publicly denounce him as a communist and a loafer. The police granted the permit but revoked it the night before and then the police rioted when the protest happened anyway.

McGuire spent much of the 1870s working as a carpenter while engaging in electoral activism on behalf of various left-wing third parties, including the Social Democratic Workingmen’s party, the Socialist Labor Party, and the Greenback-Labor party. He moved to New Haven in 1875, and then to St. Louis in 1878, where he began shifting his activism towards organized labor. He became an (unpaid) leader of a local carpenter’s union and edited a newspaper, The Carpenter. According to McGuire’s account in The Carpenter, he “was then engaged as a journeyman at the carpenter trade, and after his day’s work, devoted his time to his humble Journal and its work.”

McGuire participated in the founding convention of the Brotherhood of Carpenters, where he was elected general secretary. Pay was initially set at $15 per week (the equivalent to about $400/week or $20K/year today), but he repeatedly forfeited part of his salary in the early 1880s because the union’s finances were initially not in good shape due to low membership numbers and inconsistent reporting. McGuire was a better organizer than administrator, and made many administrative mistakes, including poor record-keeping and improperly intermingling union property with his personal property. Each time convention decided to move headquarters to a new city, he moved with it. McGuire remained a socialist for the rest of his life. When his political opponents within the union accused him of being a socialist, he wrote, “I forgive them for they deem it a term of disgrace while I regard it as a title of honor… Socialism is my faith, my religious ideal.”

In 1881, the Carpenters, CMIU, International Typographical Union, and five other international trade unions came together to form the Federation of Trades and Labor Unions of the United States and Canada, an umbrella group for all the craft unions. The FOTLU had no staff or paid officials; its single largest expense was publishing and distributing copies of its convention proceedings. It also had no central office. As was common in the nineteenth century, members of its legislative committee (executive board) mostly made decisions by paper mail or telegram. Each committee member was given a blank book and told to record all official acts in it. Samuel Gompers was elected to the legislative committee most years.

In 1886, the trade unions decided to reorganize and rename the FOTLU, founding the American Federation of Labor in its place. This time they gave the organization a central office and one paid official. According to Gompers’ autobiography:

The convention provided for a president with a salary of $1,000 per year and added as part of its constitution, ‘that the president shall devote his entire time to the interests of the Federation.’ I was nominated for president, but I was greatly disinclined to accept any salaried labor office and therefore declined. John McBride of the Miners was nominated, and he frankly stated that could not afford to accept a position to which he would have to devote his entire time upon such a meager salary. The office fairly went begging, and finally I was again nominated and persuaded in the interest of the movement to accept the nomination and election. That was the first salaried office I held in the labor movement. The convention elected as the officers of the Federation: George Harris and J.W. Smith, vice-presidents; P.J. McGuire, secretary, and Gabriel Edmonston, treasurer.

$1000 in 1886 is equivalent to roughly $28.4K in 2021 dollars. In their early days, the AFL and its affiliates thus continued the tradition of using paid labor sparingly and keeping pay low for the few officers who were paid.

Thirteen years later, in 1899, AFL Secretary Frank Morrison told the AFL’s convention:

Several of our national unions have Secretaries or Presidents who hold their office more as an honorary position receiving a nominal salary for services rendered. They work at their trade during the day and devote their evenings and Sundays to the duties of their office… National and international organizations should be urged by this convention to have at least one paid officer who should devote his entire time to the work of organizing his craft or calling.

As late as the turn of the century, there were still unions in the AFL that kept paid officers and staff to a minimum, at least on an international level.

Over its first twenty-five years, the AFL and its affiliates gradually expanded the ranks of paid officers and staff until they had a larger bureaucracy than the Knights of Labor or any previous labor union, although they still fell somewhat short of the AFL-CIO’s bureaucracy today. Gompers later wrote of his time as AFL President:

My earliest official efforts were concentrated in promoting stability of labor organizations. This had to be done by making the idea an inseparable part of the thought and habits of trade unionists by establishing a business basis for unionism and then driving home the fallacy of low dues. Cheap unionism cannot maintain effective economic activity. Sustained office work and paid union officials for administrative work have become the general practice since the Federation was organized.

Gompers correctly perceived that paid union officials were linked to the stability of labor organizations. That stability, combined with high dues, provided sufficient finances to make it possible to substantially expand the ranks of paid officials.

The process of converting officer positions into full-time careers and hiring staff varied from union to union, but it was usually done in a slow and piecemeal manner. The parts of unions involved in negotiating contracts or administering large insurance programs tended to adopt paid labor faster. Once one component of a union started paying its officers or hiring staff it tended to encourage other parts of the union to do the same, causing paid labor to spread from local to local, from locals to the international, from the international to locals, or sometimes from international to international. The Bookbinders, Carpenters, Machinists, CMIU, and the AFL itself illustrate these trends.

International Brotherhood of Bookbinders

Like other unions, the International Brotherhood of Bookbinders initially had no staff or paid officials. The growth of paid officials and staff initially occurred on a local level because contracts were negotiated by local unions. As late as 1904, the international had no full-time paid officials or staff. Officers were paid several hundred dollars per year, but still worked in the trade in addition to performing union duties. That year, the international secretary claimed he had to take a total of 100 days’ worth of leaves of absences from his regular job to take care of all union-related work his position required of him.

In 1904, the Bookbinders’ convention in St. Paul approved constitutional amendments to make the President and Secretary full-time paid officials, required to devote their entire time to the union and paid an annual salary of $1,500 each (equivalent to $45,000 in 2021 dollars). Some of the duties previously given to other officers were transferred to the Secretary, while the President was now expected to travel to locals experiencing trouble, organize new locals in locations where they did not already exist, and hire staff organizers.

Constitutional amendments in the IBB had to be ratified by referendum to be valid, leading to a lively debate after convention. Several locals sent out circulars encouraging members to vote against the amendment, prompting the President and Secretary to send out their own circular arguing that the union should give them full-time jobs. The latter argued that “it is a physical impossibility to carry on the work of the [Secretary’s] office after a day’s work at the bench and Sundays and holidays” and that “a peculiar feature issued by three of these circulars is that those issued by locals 2, 18 and 22 warn the membership against salaried officers when the fact is that all three of them have a salaried officer… and certainly if it is necessary to have an officer look after a local union, how much more necessary should it be to have officers to look after International affairs.” The initial growth of salaried officers on a local level thus legitimized the use of paid labor by the labor movement, and set a precedent that encouraged it to spread from locals to internationals.

IBB members wrote to the union newspaper arguing for and against the amendments. A member of Local 94 argued in favor of the amendments, writing: “The greatest benefit derived through association in labor unions is that of increased wages. Is it consistent for a body of men to eternally strive for better conditions themselves and at the same time protest against a law which would give their international officers equal advantages?” A member from Los Angeles similarly argued “You cannot forever retain the services of good men without fair remuneration. Why should we expect them to give their entire time to promote the usefulness of this stock company from which we all draw dividends in the shape of hours and wages without just remuneration for their toil?… Why do many locals maintain headquarters, salaried business agents? We acknowledge they are a good business proposition. In a like manner the growing affairs of the International require a paid executive head.” For these members, paying officers was an extension of their desire to make capitalism fair; union officers deserved a fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work just like everyone else.

Both supporters and opponents of the amendments agreed that the international union should have salaried officials when it was large enough and had sufficient finances to afford it, but differed on whether the union was at that point. A member of Local 31 wrote, “the financial standing of our international treasury is not good … I believe that our international should have salaried officers, who could devote their whole time to organization work, etc.; but the existing financial conditions warrant me in believing that we are a little premature.” A member of Local 2 made a similar argument, writing “our organization [is not] large enough at the present time to pay the increased salaries, as a good many locals are now in debt.” In contrast, a supporter of the amendments wrote, “Objectors to the salary idea object solely on the ground of cost… The pro rata cost or burden to each of the estimated ten thousand members will be 30 cents per year. Can it be this 30 cents some are kicking about? Is there anyone mean enough among stockholders [union members] to acknowledge he begrudges this munificent item of expense for the services per annum of these men the capacity of which they have proven to possess?” This debate highlights how financial stability was connected to the growth of paid union officers and staff in the late 19th & early 20th century.

The Bookbinders’ rank & file chose to split the difference: they voted in favor of the amendment to make the Secretary a full-time salaried officer, but rejected the amendment to do the same for the President. Their decision was something of a partial rebuke to convention, which had approved both measures by a large majority. Voters also rejected a dues increase which would have helped pay for the Secretary’s salary, imposing austerity on the International. The IBB highlights that some unions still tended to keep the use of paid labor to a minimum as late as the early 1900s and that the rank & file were generally less enthusiastic about changing that than many union officers. It shows that the growth of paid labor was often a slow, piecemeal process, and that financial stability and signing contracts tended to encourage it. It also shows how the growth of paid officers or staff in one part of the union has a tendency to encourage its growth in other parts of the union. That tendency still happens even when full-time salaried officials refrain from actively campaigning to expand the use of paid labor.

Coup in the Carpenters

Unlike the Bookbinders, the Carpenters had a single full-time paid international official from the very start. For the first twenty years, their use of paid labor did not change on an international level, but steadily grew on a district level, primarily due to the employment of walking delegates. The first walking delegate was James Lynch, who was hired by the New York City district council in July 1883 to act as what we would call a staff organizer today; his instructions were to organize carpenters working on brownstone fronts. An article in the American Federationist, the AFL’s official newspaper, would later label Lynch the first walking delegate. He was certainly the first walking delegate to be called a walking delegate, although a handful of earlier unions had experimented with similar positions before. Over the course of the decade, other district councils copied New York City and hired their own walking delegates; by 1890 one hundred had their own.

Districts gradually expanded the use of their walking delegates, piling additional responsibilities on their full-time employee, such as collecting dues, inspecting workplaces to insure compliance with union work rules, negotiating with employers, coordinating strikes, and various administrative tasks. As the carpenters began signing contracts in the late 1880s and 1890s, walking delegates were renamed “business agents” and given the responsibility of negotiating and administering contracts. As part of the contract’s closed shop provision, the union was responsible to ensure each unionized employer had an adequate supply of competent skilled union carpenters. The business agent thus became a labor recruiter — a middleman between the employer and new hires. Business agents were normally targets of hostility by employers, and sometimes of violence or threats of violence as well. Consequently, they had to become something of a tough guy. Many other AFL unions would gradually imitate the carpenters and hire their own walking delegates / business agents over the next twenty years.

As the Carpenters signed more contracts, covering more of the market, they needed more business agents to negotiate and administer them, leading to an expansion of paid officers and staff. Growth occurred primarily on the district level. Locals were often too small to afford their own business agent, but were able to band together in district councils that would pay for them. The Carpenters placed a cap upon the size of any local, but allowed multiple locals in the same city; by the end of the century it was common for cities to have multiple locals overseen by a district council. Contracts were negotiated on a local or district level, not by the international, so the need for additional staff was consequently felt on the local or district level, not the international level, first.

The proliferation of district business agents nonetheless eventually spawned campaigns to expand the use of paid labor by the International itself. Business agents or their allies were generally at the forefront of these campaigns. They felt that since the use of paid staff and officers had worked well for locals and district councils, the International ought to do the same. Additionally, the lack of paid positions in the International inhibited the opportunities for career advancement for business agents.

From 1891 to 1901, the convention, which the business agents and their supporters gradually came to dominate, repeatedly passed a variety of different proposals to expand the number of paid positions in the International, including several different proposals to hire staff organizers, to allow McGuire to hire an assistant, and to make the President and/or other officers full-time paid positions. McGuire opposed all of these proposals, maintaining the International itself should have only one paid position (his own). He supported district councils that wanted to employ business agents, but did not think the International itself should do so. Although convention passed proposals over McGuire’s objections, constitutional amendments still had to be ratified by the membership in referendum and McGuire was able to persuade the majority to vote down these proposals every time. In part, that was the result of McGuire’s continuing popularity with the rank & file. However, the members also voted down dues increases even when McGuire endorsed them. The prevailing sentiment among Carpenters at this time seems to have been to keep both salaried officers and dues to a minimum.

In the late 1890s, the business agents began to turn on McGuire himself. They did so not only over paid positions in the International, but also because they felt he did not do enough to advance the Carpenters’ interests in jurisdictional conflicts with other unions. New technologies and techniques meant it wasn’t always clear whether a particular job belonged to the Carpenters or to another craft union. By the end of the nineteenth century, craft unions in the building trades were increasingly coming into conflict with each other over which union a job should belong to, sometimes even going on strike over the issue. At root the conflict was really over which union got the dues income. McGuire was of the view that it wasn’t very important which union a worker belonged to, just that they were in a union, and so was not inclined to fight other unions when they organized workers that might otherwise be organized by the Carpenters. However, this attitude threatened the union’s finances. As organizations with significant numbers of paid staff, the district councils needed to bring in enough dues income to pay their staff, and their business agents generally found McGuire’s lackadaisical attitude towards the issue unacceptable.

In 1901, the business agents staged what amounts to a kind of coup or palace revolution against McGuire. McGuire had always been bad at administration and made many mistakes, despite being the union’s lead administrative officer. This had been the case for twenty years and was widely known among Carpenters who followed the International, but it became unacceptable now that McGuire was a political opponent. He was both physically and mentally sick at this point, and was not able to maneuver against his political opponents as well as he had done when he was younger. The 1900 convention chose to elect an anti-McGuire majority to the General Executive Board. After a series of conflicts with McGuire, the GEB filed charges and temporarily suspended him. The substitute Secretary-Treasurer found the International’s administration in a deplorable state – correspondence sat unanswered, while ten thousand dollars were missing from the union’s accounts. It is possible the missing money was used by McGuire to pay for medical expenses, but the shortage may also have been a product of neglect or erroneous record keeping. The GEB circulated the charges against him to all of the union’s members and held a referendum on permanently suspending him, which got a majority in favor but fell short of the 2/3rds needed. In 1902, convention narrowly voted to uphold the charges against McGuire and expel him from the union he had founded. Union leadership then pursued criminal charges against him, although they were never able to recover (or find) the missing $10,000. McGuire died in 1906 an absolute pauper.

The next set of leaders were far more corrupt than McGuire had ever been, and rapidly expanded the ranks of paid positions in the International. The President and many other officers were made paid full-time positions, a cadre of staff organizers were hired, and even serving on convention committees became a paid job. The Carpenters now became highly aggressive in jurisdictional battles with other unions. The new leaders abandoned McGuire’s commitment to socialism and adopted Gompers’ pure and simple unionism, becoming one of the most conservative unions in the country.

The Carpenters’ story shows several things. It highlights how employing paid staff and full-time officers goes hand-in-hand with forms of collective bargaining that are labor intensive and require specialized skills, such as signing contracts. It shows that signing contracts encourages the growth of paid labor in trade unions, and that expanding staff on one level (in this case, the district) encourages the expansion of paid staff on other levels. The coup against McGuire is also an extreme example of how employing staff can change how a union operates and erode the values it was originally committed to.

The Machinists

Founded almost seven years after the Carpenters, the International Association of Machinists began in 1888 as a fraternal labor reform organization similar to the Knights of Labor, but more racist and with membership limited to a single occupation. Initially it had a handful of paid officers and staff, like the KoL in the early 1880s, but gradually expanded the number of employees as it signed contracts, established closed shops, and ran insurance programs. In its early years, the union relied heavily on unpaid, rank-and-file members to organize. Members employed by railroads were especially effective at establishing new locals as their work often required them to travel to a variety of locations, where they recruited additional machinists to the union. In 1892, the international hired two staff organizers, but the President (then titled the Grand Master Machinist), J.J. Creamer, fired one of them because the union could not afford his salary. When the other complained about his poor salary, Creamer concluded that “the appointment of paid organizers was a bad step” and recommended districts employ organizers on a part-time basis instead.

As of 1895, the Machinists still did not provide its officers with expense accounts, prompting President James O’Connell to complain to that year’s convention, “your constitution makes a provision that the Grand Master Machinist must pay his own hotel bills while traveling for the benefit of the organization. This is certainly an injustice to your executive officer… [W]hether I or some other member will have to lead you in the future, you should not ask him to expend the greater portion of his salary for hotel bills; it is not expected that he will go begging from door to door in order that he may not have to pay for what he eats. It becomes the dignity of our order to have its representatives carry the organization to the front instead of going to the back alleys or in the slums to hide it.” In the same speech, O’Connell also encouraged locals to employ organizers, insisting that the international officers couldn’t do everything.

The next year, many locals began implementing O’Connell’s suggestion, while locals in Chicago, New York, Cleveland, and Lynn, MA went further and began hiring members to work full-time as walking delegates. Later renamed “business agents,” the Machinists’ walking delegates were expected to organize workers, do administrative work, and eventually negotiate and administer contracts. Other locals copied them, and in 1899, the international offered to pay half the salary of any local that hired a business agent.

As of 1899, the IAM had three full-time paid officers (President, Vice President / Editor, and Secretary-Treasurer). GEB members were paid a per diem of $4 per day for time spent in GEB meetings, but continued to spend most of their working time in normal jobs as machinists. A handful of additional paid positions were added over the next twenty years, including full-time salaried GEB members, but the GEB continued to have lay members into the 1920s. In 1925, they abolished the GEB and replaced it with an executive council consisting solely of full-time paid officials, eliminating the last part-time positions and completing the IAM’s transition into a full-fledged union bureaucracy.

CMIU in the Twentieth Century

The CMIU in the twentieth century illustrates the extent to which full-time paid positions grew within AFL craft unions. President Strasser left office in 1891 and was succeeded by George W. Perkins, who remained in office until 1927. The 1912 constitution set his pay at $40 per week, equivalent to $1.1k/week or $57k/year. This was more than what most CMIU members made, but below what most other international union presidents were paid at the time. They had seven numbered Vice Presidents and paid the First Vice President $150/year (Gompers held this position in addition to serving as AFL President). The Vice Presidents, President, Secretary, and Treasurer were all members of the International Executive Board (IEB) and were paid a $5 per day per diem plus railroad fare for travel.

The President was empowered to hire a range of staff members, including office assistants, organizers, financiers, and agents. The constitution required him to hire at least six organizers, and authorized each organizer to hire sub-organizers “to be under his immediate control and direction.” Each sub-organizer was to “work at trade whenever practicable, the amount of money so earned to be deducted from stipulated salary.” Although they did recruit new members and organize new locals, organizers and sub-organizers spent much of their time engaged in marketing cigars with the union label. The CMIU constitution set minimum pay for organizers and financiers at $21 per week (equivalent to about $600/week or $31,000/year in 2021 dollars), plus $2.50 per week for railroad fare and expenses, but the IEB could pay more and had veto power over the President’s hiring decisions. Agents were hired by the President to oversee strikes and participate in contract negotiations; they were paid at a lower rate of $20/day plus travel fare and $2 per day in expenses. Additionally, a number of convention roles were paid, including a clerk and stenographer, and a $5 per diem for delegates. The union also paid the international ballot committee, recruited from several different locals, $5 per day plus railroad fare. Most jobs were only open to workers who had been members of the CMIU for a certain amount of time, which was a common requirement for union staff before the 1950s.

On a local level, most officers were paid at least a small amount by the early twentieth century. The local secretary or secretary-treasurer was often a full-time paid officer, although in smaller locals it was usually only a part-time job. A few of the larger locals hired a handful of staff, although in some cases, positions you would expect to be staff were actually elected officers. For example, in Chicago the janitor for the union hall was elected.

The CMIU shows the extent to which the use of paid officers and staff grew over the late 19th & early 20th centuries. The use of paid labor on this scale was only possible because the CMIU’s insurance programs, high initiation fees, high dues, and, in some cases, contracts with closed shop provisions ensured it had a stable membership that provided it with a consistent income high enough to afford its employees. The existence of paid agents to oversee strikes and help negotiate contracts highlights the role that contractualism played in encouraging reliance on paid staff. Insurance administration was primarily carried out by the International President, local Secretary, and local Town Collector, all of whom were paid officers. Union insurance programs thus not only encouraged the use of paid labor by ensuring the union had a larger dues base, but also necessitated that the union pay more people to administer those same programs. The original intention of ensuring that unions had a stable membership and a sizable, steady income was to strengthen the labor movement, not to employ people per se, but the byproduct was nonetheless to increase trade unions’ reliance on paid labor.

A Practical Business Administrative System

The AFL itself also expanded its reliance on paid officers and staff, but at a slower rate than many of its larger affiliates, because it usually was not directly involved in negotiating contracts or managing insurance programs. In 1887, the AFL authorized its President to commission organizers, but they were all volunteers initially. In 1890, the convention authorized the executive council to pay organizers, but pay was low or limited to covering their expenses for several years; it was not a full-time job. Gompers wrote in his autobiography:

Until 1891 I was the only full-time official of the Federation. This meant I had to be responsible for practically all the work of the Federation. Finally, I protested to the Executive Committee urging that I be relieved of the financial work and that a resident secretary be provided to assume full responsibility for that work. This was done in the 1890 convention, and Chris Evans of the Miners was elected secretary.

The 1890 convention thus marked a shift away from its previous policy of only having one paid official, towards gradual expansion of paid labor, with two full-time officers and some part-time staff organizers. This was the same year AFL membership reached 100,000, surpassing the declining Knights of Labor for the first time.

The AFL’s small bureaucracy continued expanding over the course of the 1890s. Its financial records for 1894 show it paid the President $1,800 (equivalent to $56k in 2021 dollars), $1,500 to the Secretary (equivalent to $48k), $100 (equivalent to $3k) to the Treasurer, $748.50 (equivalent to $23k) for a clerk, $663 (equivalent to $21k) for a stenographer, and $224.50 (equivalent to $7k) for an office boy. In his memoirs, Gompers wrote that in 1896, “we added a second stenographer, a typist, a shipping clerk, and an office boy.” (Their records show an office boy was already on the payroll two years earlier; Gompers may have misremembered the exact year he was hired.) Gompers was proud of the extent to which bureaucracy in the AFL and its affiliates had developed by this point, and explicitly linked it to workplace contractualism:

In 1896 the Federation was established as a permanent organization and had no competitors. We had developed discipline as an essential of trade unionism… A practical business administrative system within unions had provided offices, salaried officials, and the beginnings of systemic labor records. All these things were necessary to sustained contractual relations with employers. The trade agreement we had found to be an important instrumentality in advancing toward the goal of trade unionism.

The use of paid labor by the AFL continued to grow over the next several decades. Its financial records for 1899 show that, in addition to (unchanged) salaries for officers, it spent $1,490.84 on clerks, $2,116.67 on stenographers, $15 for a part-time janitor, and $5,324.10 on “organizing expenses” (which probably included pay and expenses for organizers). Convention that year then raised both the Secretary’s and President’s salary by $300 each. The 1912 AFL constitution left the salaries of the President and Secretary up to convention, set the Treasurer’s annual salary at $500, and set “remuneration for loss of time by members of the Executive Council,” organizers, and speakers, at “$6.00 per day, hotel expense, and actual railroad fare.” At the time, the Executive Council consisted of the President, Secretary, Treasurer, and eight Vice Presidents, all of them elected by convention. The President’s annual salary was further raised to $3,000 in 1902, $5,000 in 1907, $7,500 in 1914, and finally to $10,000 (equivalent to $157,805 in today’s dollars) in 1919. That year the AFL also directly employed one-hundred and twenty-five full-time staff organizers.

In the twentieth century, it became increasingly common for unions to pay their top officers substantially more than what their members made. In part that was due to higher income from more members, which grew significantly from 1898-1903 and 1914-1919. It was also a product of unions copying each other’s policies on paid labor. Pay increases were frequently justified by citing the salaries of other labor leaders. A 1907 letter in the ITU’s Typographical Journal argued for raising the salaries of the President and Secretary-Treasurer on the grounds that other unions already paid more:

What do the railway engineers and firemen, who pay their executive officers $5,000 a year, think of us? Or the mine workers, who pay their president $3,000 and their secretary $2,400, or the glass bottle blowers, who pay their President $2,400, or the carpenters, who pay $2,000? Do they not think it queer that we can secure competent help for the salaries we allow?

$5,000 is equivalent to $145,000 in 2021 dollars, while $3,000 is equivalent to $87,000, and $2,000 is equivalent to $58,000. Pay increases tended to spread from union to union within the AFL, much as the conversion of union officers into full-time jobs had spread from one part of the union to other parts, and then from union to union.

Any change a union makes to its employment practices may ripple outward to other locals, branches, departments, positions, levels, and unions. A change may only be intended to address a particular job for a particular purpose, but it nonetheless has broader implications. That change will be cited by others to justify copying it, and, if it increases someone’s pay or adds additional people to the payroll, will create a constituency with a vested interest in perpetuating and expanding it. Haphazard or ad hoc employment policies can have unexpected results when those policies are copied by other union bodies in different contexts. Employment policies that are applied on a case-by-case basis, not thoroughly thought out in a systematic fashion, can result in runaway growth of the bureaucracy. Once a union starts expanding its payroll it can be difficult to stop unless it runs out of money.

The first thirty years of AFL history show that, although unions can rely mainly on volunteers, certain practices will tend to encourage them to shift towards staff-driven unionism. The ancestors of today’s unions were at first volunteer-driven; they demonstrate that unions do not have to be staff-driven but also that volunteer-driven unions can drift into staff-driven unionism as a byproduct of other seemingly unrelated choices. Any practice that is labor-intensive and relies on specialized skills and knowledge – like negotiating contracts – is likely to encourage the union to rely more on paid officers and/or staff. Any union that has a growing income for a long enough time period is likely to eventually start spending some of that income on officers and staff unless that money is clearly earmarked for something else or the union has firm rules against it. How a union organizes and how it employs officers and staff are linked; one affects the other.

Robin J. Cartwright is a former labor historian, with a PhD in late-nineteenth century U.S. working class history. He is a member of the IWW and a former elected department representative of the Communication Workers of America.